This article was originally published in 2012. It has been republished here upon Karl Lagerfeld’s death at the age of 85.

Two days before the Chanel couture show last July, Karl Lagerfeld and I were talking in the Chanel studio on Rue Cambon. After four months of incessant rain in Paris, it suddenly was beautiful outside, and the windows were open. Amanda Harlech and Virginie Viard, two of Lagerfeld’s intimate collaborators, were working on fittings. A photo shoot for W starring both of them—along with the rest of Lagerfeld’s muses—had taken place a few days earlier, and at his suggestion, they had all agreed to be photographed dressed as cats. Lagerfeld has an 8-month-old kitten named Choupette, who increasingly plays a central role in his emotional life, and I started to wonder—not without reason—why Lagerfeld had wanted the women to resemble Choupette.

Jamie Bochert had just finished her fitting. Twenty-nine years old, long and austere, with a mien like Patti Smith’s, Bochert is more musician than model, but Lagerfeld was so infatuated with her that he used her as his only model for the couture-collection press kit. “She’s going to star in a film I plan to make on the life of Catherine Pozzi, the mistress of the poet Paul Valéry,” Lagerfeld told me. And then he started to recite fragments of poetry. To hear him suddenly declaim “Mon coeur a quitté mon histoire” (“My heart has left my story”) seemed to illuminate all the contradictions in which Lagerfeld finds himself embroiled: He is a man whose exterior protects a heart that some believe went off course many years ago. But did it truly? I’m not so sure. “It’s lovely, right?” he said of the line, staring at me from behind his dark glasses.

In the interest of full disclosure: Though I don’t work at Chanel, I have known Lagerfeld for more than two decades. In the early eighties, when I was in my 20s and a model, I met him during his tenure at Chloé. He was heavier, his hair was longer and already in a ponytail, his eyes were masked by dark glasses, and he held a fan that evoked the Versailles court. (Of course, the fan has since been replaced by the signature fingerless gloves—there’s always something to hide with him—but we’ll come back to that). When he first met me, he exclaimed that I resembled Françoise Dorléac, Catherine Deneuve’s older sister, who died in 1967. The comment was at once flattering and peculiar. There was—and still is—nothing more repulsive to Lagerfeld than death and all it entails: funerals, weakness, illness, the past. Every one of the women close to him—the Chanelettes, if you will—whom I met with agreed on this point. Lagerfeld, though, has no difficulty whatsoever squaring his denial of death with an equally pronounced habit of invoking the past—in particular, female figures of bygone eras who are imbued with a beauty or spirit that he believes transcends their time.

Coco Chanel, along with Lagerfeld’s mother—both of them adored and faux-mocked by the designer, omnipresent and utterly dismissed, formative and destructive—haunt the conversations inside the Chanel headquarters. If gloves are an intrinsic part of Lagerfeld’s ensemble, it’s because his mother told him a long time ago that he had ugly hands; he’ll say so himself. Yet when, many years ago, Chanel model and muse Inès de la Fressange took Lagerfeld to a restaurant on the Champs-Elysées and told him that she thought his mother had had a definitive influence on him, “he genuinely seemed surprised,” recalled de la Fressange. Harlech, a Chanel consultant since 1997 who is among the most intuitive of the Chanelettes, told me: “The mother is there immediately—all the time. One cannot compete with her. She was supremely intelligent, cultured, complicated, and demanding—an artist.” The portrait that seemed to be emerging was that of a woman who essentially never let Lagerfeld be a child. “She constantly encouraged her son to be intellectually brave—and to sharpen his wit.” Because of this, Harlech added, “on this terrain, he’s like an Olympic swordsman.”

Top row, from left: Jamie Bochert and Maïwenn Le Besco. Middle, from left: Virginie Viard, Inès de la Fressange, Amanda Harlech, and Marie-Louise de Clermont-Tonnerre. On floor, from left: Violette d’Urso and Laetitia Crahay. All wear their own clothing and accessories. Styled by Amanda Harlech. Photo by Karl Lagerfeld.

Anna Mouglalis, an actress and model who has worked as a Chanel brand ambassador for more than a decade, has her own take on Lagerfeld’s famed wit. “I met Karl for the first time in 2001 during a photo shoot for W. I thought I would find absolute superficiality, but instead I discovered a scholar who plays on superficiality. If it weren’t for him, fashion would not have interested me. He’s someone who’s always working on himself—which, of course, he denies. He has a Calvinist side that has elevated work to a place of absolute value. When he holds you in his esteem, it means he’s recognized a talent in you, and he demands that this talent surprise him—that it reach its full potential. He’s a glorious Pygmalion.”

Lagerfeld often gives books to Harlech and Mouglalis, though he bestowed upon Harlech something even more essential at a crucial time in her life. In 1997, when Lagerfeld still lived on two floors of the Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo on Rue de l’Université, John Galliano was hired by Dior. The maison, however, didn’t offer Harlech—then Galliano’s collaborator—what she considered to be suitable financial terms. “I was divorcing, and I didn’t have enough money to maintain my house and give my children a good education,” said Harlech, a fleeting hardness passing through her sapphire eyes. When Lagerfeld became aware of her dilemma, he made her an offer that Dior could not match—and that Harlech could not refuse. “Since then,” she continued, “I’ve made the transition from performing monkey to learning speed, precision, and concentration. Sometimes Karl and I read the same book, but he finishes it more quickly than I do. Other times, he looks over my shoulder while I work on a watercolor. His intellectual and spiritual bravery often hide his poetry.”

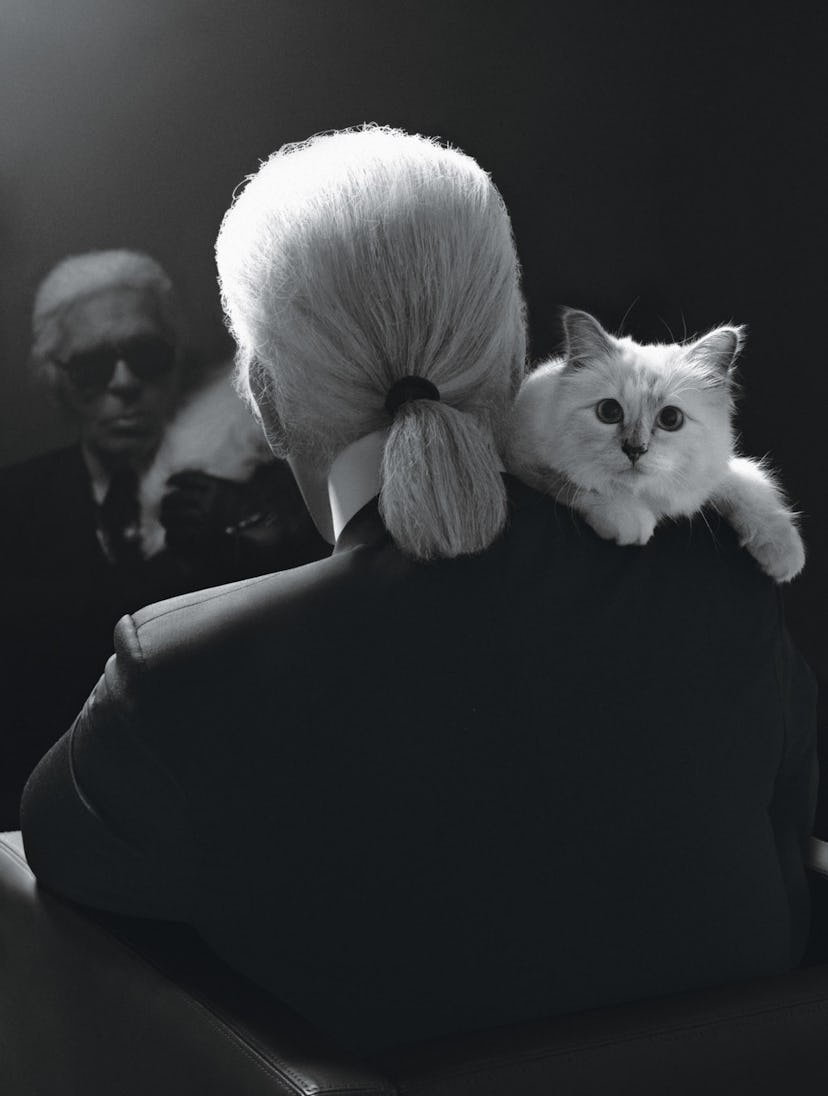

Lagerfeld’s almost familial sense of loyalty is well known—lately, he’s begun to refer to certain boys around him, including the model Brad Kroenig and Kroenig’s 4-year-old son, Hudson, as his “adoptive sons.” But the latest object of his affections is undoubtedly Choupette. Indeed, it was only after Lagerfeld showed me iPhone photos of the kitten next to him on a desk while he was sketching, and waiting for him on his bed, and at the edge of the tub at bath time, and wrapped in the antique linens Lagerfeld loves so much, and playing on an iPad with her paw that I realized that those who still think of Lagerfeld as Louis XIV have clearly understood nothing. When he sends text messages to Virginie Viard—his studio director and collaborator since 1987—he pretends the kitten is speaking for him. “He signs them, Your Choupette,” Viard said, noting that along with the text comes a photo of the blue-eyed feline. Then she worried: “He might not like that I’m saying this.” After all, the man she is describing seems to be a long way off from Lagerfeld’s intimidating public persona.

Viard—whom the ladies of Lachaume, Lagerfeld’s florist, telephone quietly for help deciphering the handwritten notes accompanying the bouquets that the couturier regularly sends out—is one of the only women around Lagerfeld to use the familiar French tu with him. She’s also one of the only ones to invoke the death of Jacques de Bascher—the man some call the love of Lagerfeld’s life—and his 1989 funeral, which Lagerfeld asked her to attend. “I saw then that I was among those who mattered to him,” she told me. Viard is eminently discreet, the consummate professional—I’ve seen her take Lagerfeld’s hand during fittings in a manner that is at once tender and authoritative, particularly when the clock is ticking and there are technical details to address. “So many people are afraid of him, and that’s the worst thing,” Harlech confided. “It shuts the door immediately. What he likes is that one be engaged in conversation—and more than anything, that one be informed.”

Inès de la Fressange, who was already Lagerfeld’s muse when he arrived at Chanel in 1983, remembers that “once or twice, he told me I’d done my hair like his mother, who lived on the Left Bank and wore Rykiel.” Their first meeting took place while Lagerfeld was at Chloé and de la Fressange had been working for the biggest names in fashion—“forty-two shows in one season, among them Mugler, Montana, and Gaultier,” she recalled. Though she was regularly sent to Chloé by her agent, something about it never worked; she never even got to meet Lagerfeld. One day, however, on an appointment at the house, she ran into him. “He said to me, ‘Ah, you finally come to see me! I thought you worked only for Mugler!’ ” de la Fressange said. “He was pretending to be misinformed.” She walked his runway, and they became inseparable. Lagerfeld so adored this tall, spirited French girl that he took her everywhere.

Choupette readies for her moment in the spotlight.

“One day Karl told me he was invited to fly on the Concorde to go hear Aida at the Egyptian pyramids,” de la Fressange continued. “He couldn’t decide—sleep there, or make the return trip? I told him that going for the opera, having dinner, and coming right back would be much more fun.” And so, it was done. “On tour with him in the U.S., in a private jet,” she said, “I noticed that I was the only model to do everything with him.” De la Fressange spoke for Lagerfeld, socialized with him, did press for him, and charmed the public with personal appearances at big American stores. In Chicago, they got hungry in the middle of the night—before his famous protein diet, Lagerfeld permitted himself everything—and found a tiny café. Lagerfeld, dressed in black tie and holding the ever present fan, took out a $100 bill for a hot dog “and then fell asleep in the car like a big baby,” de la Fressange said—before noting with a tinge of regret how Lagerfeld would hate reading that last line.

Though the two had a falling-out in 1989 and have only recently reconciled, de la Fressange clearly feels a connection with the designer that’s both sincere and profound—so much so that she won’t talk about it openly, to avoid embarrassing Lagerfeld. The source of their break, far from the usual tension over sharing the spotlight, was actually over sharing de la Fressange herself: She’d met Luigi d’Urso, a man who was her twin in both slenderness and spirit, and fallen in love. “Karl didn’t impress him,” de la Fressange says. “And Luigi made zero effort in front of him. He always kept his distance.” The final straw came when the government of France asked de la Fressange, who was 32 at the time, to lend her likeness to the Marianne statue—the feminine symbol of the Republic that stands in all the town halls of that country. The media adored this story; Lagerfeld, much less so. “He didn’t find it chic,” de la Fressange said, “and asked that I refuse. Against his wishes, I accepted. And once he feels abandoned, he turns naughty—like a little boy.”

With Lagerfeld, the seismic shift of falling out of love always seems directly proportionate to the amount of affection involved. During the legal aftermath of their rupture, de la Fressange was advised by the powerful lawyer Georges Kiejman; ultimately, she won a substantial settlement. Today, however, one can often see the 13-year-old Violette d’Urso, one of Inès and Luigi’s two daughters, alongside Lagerfeld during fittings at Rue Cambon (Luigi died of a heart attack in 2006). In fact, upon learning that Lagerfeld was spending last Christmas by himself, Violette demanded of her mother: “How can we leave him alone!” De la Fressange still laughs about it. “I was forced to send this grotesque text message—‘You’re welcome at the house for Christmas…’ ” On Christmas Eve, Lagerfeld sent over a shower of gifts but didn’t show up. “Violette worries about him,” said her mother. “She truly loves him.”

Laetitia Crahay was 24 when she met Lagerfeld in 2000 after working as the artistic director for Olivier Theyskens’s sensational debut. “I arrived at Chanel by skateboard,” she told me. “And what ended up taking place wasn’t really an interview but rather a quiz.” Though Crahay seemed to respond correctly to all the questions, “we almost fought about a bracelet I was wearing that Karl insisted was from the 1950s,” she said, “while I maintained that it was from the forties.” She was hired on the spot and hit the ground running—and fighting. “One day, I was tempted to put my bag in the mouth of a taxi driver who was saying things that weren’t true about Karl,” Crahay said. Soon she became responsible for Chanel’s jewelry and accessories, and since 2006 she has also been artistic director of Maison Michel, the hatmakers acquired by Chanel in 1996. It’s clear to her that the loyalty she feels toward her boss is returned. “Karl has genuine intentions for the people he loves,” she said. “He keeps his promises.”

When she arrived on the set of the shoot with Lagerfeld and the Chanelettes, the actress, screenwriter, and director Maïwenn Le Besco, who recently joined Chanel as the new face of the Prestige eyewear campaign, seemed to be in a hurry. Moments later there was a flurry of activity as Choupette appeared in the arms of the professional cat sitter Lagerfeld keeps on his staff. Everyone vied for a moment with Choupette, as Le Besco waited patiently, looking at her watch. Having known Lagerfeld for far less time than the other women had, she seemed to stay on the sidelines. “Karl is someone who’s more attentive than affectionate,” she said from behind her Catwoman mask. “For affection, you need the passing of time.” Someone casually mentioned that with this shoot she was becoming part of the family. “Not part of a family,” she snapped, like a cat that’s been rubbed the wrong way. “Part of a house.”

Whether he’s thinking of his friends as family or he’s strictly concerned with the functions of the maison, though, Lagerfeld has always been more than generous to those in his favor. He’s gifted 18th-century furniture to de la Fressange, and he often surprises friends and colleagues like Viard and Harlech with jewelry. The legendary Marie-Louise de Clermont-Tonnerre, a veteran who has been at the company for 41 years and has headed its international public relations since 1971—two months after the death of Mademoiselle Chanel—showed me a series of drawings by Lagerfeld when I visited her. “When I had the apartment insured,” she told me, “the appraisers valued some of his drawings more highly than some of my pieces by Cocteau.”

But that generosity extends beyond the mere bestowing of presents and bijoux. Four years ago, Lagerfeld handed me a check for 15,000 euros intended for Birgitte de Ganay, a mutual friend whom he no longer saw but who was facing an extreme psychological and financial crisis. No doubt Lagerfeld remembered the fierce allure of this stunning Danish beauty, though when he wrote that check, de Ganay was far from the sparkling worldly figure he’d known. We’d just finished a day of shooting for Le Figaro, where I work, and were looking at the pictures. In a tone that I now understand was meant to eschew sensitivity, Lagerfeld summoned me unexpectedly into a hallway and brusquely stuffed the check into the pocket of my jacket. There was nothing patronizing about it—just an immense terror of being caught, in flagrante delicto, having a heart. (De Ganay committed suicide two years later.)

De Clermont-Tonnerre—who called Lagerfeld “Monsieur” when we started our conversation and later switched to “Karl”—has experienced firsthand this side of him. “At a difficult moment in my life, he forced me to hold up my head, to get dressed, to take care of myself,” she said. But like all the others, de Clermont-Tonnerre feels compelled to shine, to please, under Lagerfeld’s influence. “One day I wore pants and flat shoes,” she told me. “It was the first and last time. Karl looked at me with total disapproval and said, ‘But Marie-Louise, when one has your legs…’ I’ve never done it again.”

“He isn’t lacking in contradictions,” Mouglalis admitted to me. The extreme fear Lagerfeld feels about being unloved explains both the profound attachment he shows for his Chanelettes and the brutal fall from grace that certain people have experienced as soon as the threat of hurt or abandon arises. But one could argue that behind his facade is an immense need to love and to be loved, to give and to receive. In the end it occurred to me that, against all expectations and in defiance of his notoriously thick skin, Lagerfeld might just be a softie.

As I considered the thought, I was reminded of the words that had brought Viard to tears in the middle of our interview in the Chanel atelier as two young assistants sat nearby, neither of them daring to speak. Viard had suddenly recalled how 10 years ago, as her grandmother, to whom she was very close, neared death, Lagerfeld—seeing her sadness—approached her. “You know,” he said, “one day you won’t have me anymore, either.”

And what will she do then? Viard, along with the rest of Lagerfeld’s Chanelettes—having learned from the master—knows that the best thing is to not even think about it.