14 Revelations from the New Alexander McQueen Documentary

From sewing human hair and secret messages into his garments to his penchant for Sinéad O’Connor.

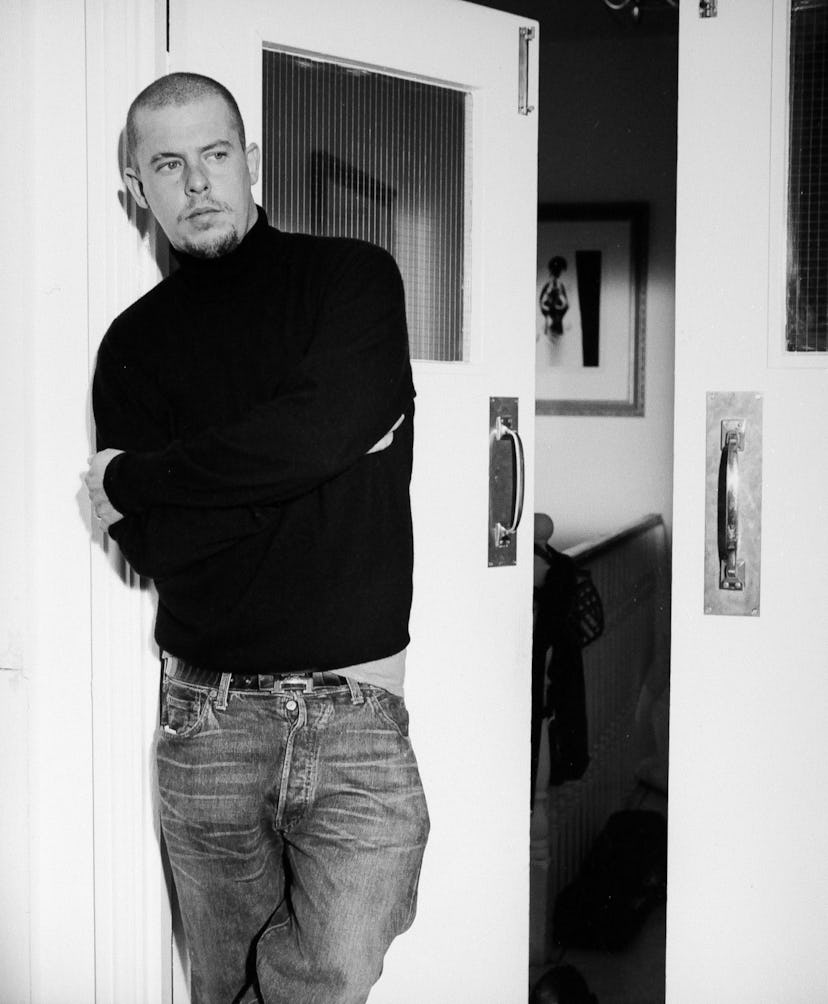

It’s been eight years since Sarah Burton took over as creative director of Alexander McQueen following the designer’s death, yet Lee Alexander McQueen, who was already a cult figure before he took his own life in 2010, still looms large over the brand that bears his name. His story has become myth: the tailor’s apprentice from south London who, after graduating from the famous Central Saint Martins design college in 1992, went on to define the stakes of ’90s fashion. By 27, he had been appointed head designer at Givenchy, much to the outrage of French fashion, around the same time that Tom Ford was selected to head Gucci and John Galliano was installed at Christian Dior, initiating a paradigm shift in some of the most fabled houses in fashion. (McQueen once described his tenure at Givenchy as “like taking a dinosaur out of the sea,” according to his late mentor Isabella Blow.)

The new documentary McQueen, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival on Sunday, both analyzes the origins of the McQueen mythos and aims to peel it away, discussing the designer’s work, personal life, and legacy through archival footage and interviews with some of his closest friends, collaborators, and family members, including McQueen’s sister Janet and his nephew and Janet’s son Gary James McQueen. (A note at the end of the film states that it was not authorized by the McQueen estate or the Alexander McQueen brand, which is still owned by Kering.) The film offers a comprehensive survey of McQueen’s career, from the ateliers of Savile Row to the halls of Givenchy, and his concomitant struggles with mental illness and addiction. (It glosses over his relationships with celebrities famous for wearing his pieces, like Lady Gaga and Sarah Jessica Parker, though the likes of Grace Jones and Janet Jackson appear in some archival clips.) Unspoken, but equally evident, is McQueen’s continuing influence on younger designers like Charles Jeffrey, himself a Central Saint Martins alum and kilt aficionado, and Iris Van Herpen, a former McQueen intern whose eponymous label is best known for 3-D printed pieces.

All this is to say, the rough contours of McQueen’s history are well known even beyond fashion cognoscenti. During the premiere screening of McQueen, the audience’s relieved laughs at occasional moments only underlined the tension as the film sped towards its poignant conclusion, with McQueen’s suicide on the eve of his mother’s funeral. But there’s still plenty of material to mine: “Because his shows were so autobiographical, you could tell the story of his life through his shows,” writer and codirector Peter Ettedgui said during an audience discussion. Here, the 14 most memorable revelations from the new documentary, which is slated for release this summer.

McQueen’s mother encouraged him to make clothes in the first place.

After Joyce McQueen saw a news report describing the dearth of young tailors on Savile Row, Joyce suggested her son seek out an apprenticeship; after all, he had spent his childhood sketching looks when he should have been studying biology. This led to positions with Anderson and Sheppard, Koji Tatsuno, and Red or Dead in London, and with Romeo Gigli in Milan.

McQueen loved Sinéad O’Connor.

“He really liked Sinéad O’Connor,” said John McKitterick, the designer for Red or Dead during McQueen’s time there. “I always remember him walking along, listening to Sinéad O’Connor.”

McQueen started sewing secret messages into garments before he even launched his label.

Though McQueen could draft a jacket freehand, according to his one-time boyfriend and design assistant Andrew Groves, his talents were apparently not up to snuff for Romeo Gigli. McQueen worked in Gigli’s Milan atelier from February to November 1990; at one point, Gigli pulled apart the seams of a jacket made by his young assistant, demanding he remake it. McQueen complied, only to have Gigli tear up his work again. The third time, though, when Gigli pulled out the stitches, he found a message waiting for him in the lining of the garment: “F— you, Romeo.” (McQueen is rumored to have hidden a similar missive in a jacket he made for Prince Charles—a legend that may have been borrowed for Daniel Day-Lewis’s Phantom Thread character, Reynolds Woodcock.)

McQueen’s graduate collection for Central Saint Martins used human hair.

McQueen presented his debut collection, “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims,” in March 1992. Among his research materials was the Patrick Süskind novel Perfume: The Story of a Murderer; one of the resulting garments, a pink overcoat patterned with barbed wire, was in fact lined with human hair. (Perhaps a different kind of secret message sewn into the piece.)

Isabella Blow told Lee to design under his middle name, Alexander, because it sounded “more posh.”

This was after she saw his graduate collection and called McQueen’s home between six and eight times a day until, finally, he picked up.

Though widely criticized as misogynistic at the time, “Highland Rape” had deep personal resonance for McQueen.

“I honestly thought that he just really didn’t like women, he didn’t like models, he didn’t like anything,” said the model Jodie Kidd, who was 15 at the time of McQueen’s infamous “Highland Rape” show. The inspiration for the fall 1993 collection was twofold: It combined the designer’s Scottish heritage, which his mother had recently begun to explore, with his own experiences of abuse—he and his sister were both abused by her husband, McQueen’s brother-in-law, when he was a child. “A man takes from a woman,” McQueen said in an interview at the time of the collection; Groves described its looks as “almost confessional.”

McQueen refused to show his face to the press during his first few seasons because he was technically unemployed.

Some of McQueen’s earliest looks were as groundbreaking in silhouette as in budget-consciousness: a swaddling of lace, for example, with a zipper sewn into it. (According to groomer Mira Chai-Hyde and Groves, these garments may have cost just £10 to make.) As an emerging designer from a working-class background, McQueen had limited resources at his disposal to invest in his brand’s first seasons; he “survived on unemployment benefits and I bought all my fabrics with my dole money,” he said in an interview at the time. “I went round to my parents’ for baked beans and tins of soup, things like that.” (“We were paying him to work for him,” revealed Alice Smith, a friend and agent.)

Joyce McQueen brought the models homemade sausage rolls backstage of “Highland Rape.”

Also on the menu: sandwiches.

McQueen infamously said Givenchy was a “load of crap”—and then he was appointed its head designer.

He and Rebecca Barton, a designer with whom he attended Central Saint Martins, crashed a Givenchy show when they were in school, at which point he described the brand as a “load of crap.” So why take the position? “The money was good,” McQueen reportedly said.

McQueen made “The Search for the Golden Fleece,” his 55-look Givenchy debut during the spring 1997 couture season, in just 25 days.

“We don’t come up with ideas until the very last moment,” he said at the time.

Tailors weren’t allowed into the design atelier at Givenchy—until McQueen took over.

When making his first collection for Givenchy, “Lee wanted to see the person who has worked directly with the garment,” according to assistant Sebastian Pons. So he invited Catherine de Londres, the head of the tailoring staff, into his atelier, unintentionally subverting decades of tradition. He also tended to eat in the cantina with his staff. “Lee didn’t want to behave like a king,” Pons said.

McQueen dedicated “13,” his spring 1997 show, to his dog, Minter.

After the show’s finale, in which the model Shalom Harlow spun round on a revolving platform embedded in the stage while robotic arms spattered her with jets of paint, McQueen took a victory lap with his two dogs. (By the time of his death, McQueen owned three dogs; his will set aside more than $80,000 to cover their care.)

His work elicited the envy of one Tom Ford at Gucci.

In an old interview woven into McQueen, Ford wondered, rhetorically, “Whose collections am I jealous of, in a sense?”

When asked if he would let another designer take over his namesake brand, McQueen said, “I don’t think so.”

HIV-positive and struggling with cocaine, he was confronted with mortality—both his own and that of those closest to him—toward the end of his life. Though his relationship with Blow suffered when he didn’t hire her at Givenchy, he was nevertheless devastated by her suicide in 2007; he and milliner Philip Treacy, another Blow protégé, dedicated McQueen’s “La Dame Bleue” spring 2008 collection to their late mentor. As recounted in McQueen, the designer also had the grim idea of staging his suicide as the finale to “Plato’s Atlantis,” the spring 2010 show that would turn out to be his swan song.

He also wrestled with simply quitting fashion; creating as many as 14 collections per year had taken its toll after nearly two decades. Yet McQueen refused to kill the brand, just as he refused to hand it over to someone else. Despite their grand, theatrical scale, McQueen’s shows were intimate in theme; the brand was inextricable from the man himself. “If I had a bad day, I’ve only got myself to answer to,” he declared.

McQueen also once said, “If you want to know me, just look at my work.”