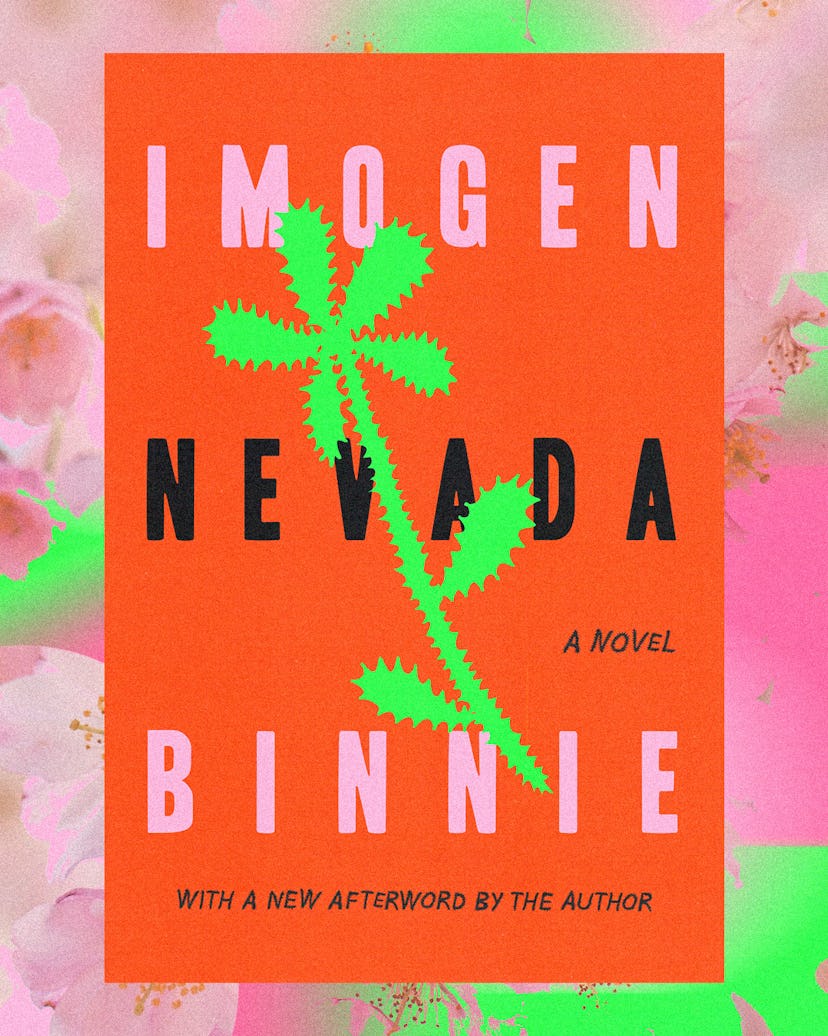

“A lot of people have read Nevada and said, ‘That book made me figure out I was trans,’ ‘That book saved my life,’ or ‘That book made me realize that I don't have to be as alone as I have made myself be,’” Imogen Binnie tells me just a few weeks before her cult classic novel, Nevada, would be re-released. “I hope that more people read it and go, Holy shit, this has made my life feel possible.”

Originally printed in 2013 with Topside Press, a now-defunct publisher of trans and feminist literature, Nevada tells the story of a punk transgender woman verging on 30 named Maria Griffiths, who embarks on a journey to the western United States after losing her bookstore job and breaking up with her girlfriend in Brooklyn. Upon arriving in the outskirts of Reno, Maria meets James, a Walmart worker whom she is convinced is actually transgender and in need of saving.

While writing Nevada, Binnie was living in a queer communal house in Oakland, California. She had just left New York City, and lacking any fellow trans women to confide in, she describes herself as “feeling out of place” back then. The sense of isolation that developed during her time on the west coast became the catalyst for writing the book.

Although Nevada has been out of print for a number of years, it has accrued an impassioned fanbase and is considered to be part of the queer literary canon. The novel, now re-released by top publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux, is interspersed with frank musings on addiction, dissociating during sex, gentrification, and how trans women struggle to find solace online and offline in the 21st century. It’s both very much of a specific era—there are references to MySpace and polemical language about how Williamsburg once “seemed like a scary, tough neighborhood”—and timeless, brilliantly delving into the constant hum of self-consciousness that emerges when one is pushed towards the margins.

Now living in the woods of rural Vermont with her partner of 16 years and two young children, the 43-year-old novelist holds a day job as a therapist, has an IMDB page of TV writing credits, and describes herself as worlds away from the chaos that once inspired her messy, lovable characters.

Much like her protagonist Maria, Binnie grew up surrounded by dull cow farms in western New Jersey and turned towards books as a means of escape. “There's this thing about not knowing how to be a person when you don't know how to be a gender, and you lose that internal sense of being able to trust yourself to reach out towards things,” she remembers during our Zoom call together. “Whereas if you're a kid [who is a reader], that is very much rewarded. It was a thing that felt good when it was hard to find other things that felt good.”

As a college student at Rutgers University in the late ’90s, Binnie became immersed in the discreet corners of the Internet where LGBTQ+ people were logging on to find the kind of camaraderie and answers they couldn’t get in their daily lives. Long wanting to be an author, she began writing stories on FictionMania—a transgender erotica fiction website that hosts tens of thousands of short stories. “It never really felt like a great fit to be writing there,” she says. “But at the same time, it was kind of like the best thing I've ever found.”

She also started a secret LiveJournal blog to connect with other netizens to process “gender stuff” and joined strap-on.org, an ultra-political queer message board that Binnie describes as a canary in a coal mine for today’s “social justice warriors.”

Hearing Binnie recall the early Internet, the initial promise of the web is illuminated. Before “getting canceled” and “stanning” became overwrought terms, isolated individuals from all over gathered on listservs, chat rooms, and message boards to exchange information, and though Binnie says disagreements quite often resembled the ugliness that’s lurking on today’s social networks, the sense of potentiality made it worth it. “That first engagement with critical thought around marginalized people and how that stuff works is both exhilarating and terrifying,” she recalls.

It took a while for her interests in literature and queer community-building to intersect. In her offline life, Binnie characterizes her early twenties as “a mess” filled with drinking and figuring out her transition. At the age of 22, she graduated, moved to New York City, and got a job at The Strand—the iconic East Village independent bookstore. In 2006, she went to Camp Trans—an event that was meant to protest a trans-exclusionary feminist musical festival in rural Michigan. There, Binnie met her now-wife and engaged in candid conversations about gender and sexuality with other attendees that she had once solely had on message boards.

When I proposed to Binnie that Nevada was a product of her own experience floating through digital and IRL queer spaces in search for guidance, she agrees. “Everybody who was like ‘This is how to be trans’ was doing it in a way that didn't resonate, so I wrote a book about somebody who was trying to tell somebody else how to be trans and it didn't resonate,” she says.

Binnie started writing a manuscript in 2008, and several drafts later, published it with Topside Press in 2013. Nevada spread through Tumblr and by word-of-mouth. On a book tour across North America, she noticed that trans women were ecstatic about gathering in an offline space. Binnie often invited her attendees to read their own material to make the event feel relaxed and informal. While getting drinks with friends at a bar following an event in Chicago, she befriended a shy trans woman lingering around and later learned that that night was her first time publicly expressing her gender. After founding a Bay Area group for transgender women with comics writer Joey Alison Sayers, this book tour was an extension of Binnie’s earlier efforts to get transgender people to coalesce and have something—whether in the physical or digital realm—to call their own.

Ana Valens, a reporter who published an essay in 2017 about why she personally connected with Nevada, believes that the novel's success stems from the depiction of Maria as a “nervous and uncertain trans girl who overthinks her life and dumps her trauma and shit onto someone else.”

“For Imogen to capture this [she] required a certain level of honesty and vulnerability about trans women in all their humanity,” Valens tells me via email. “We are survivors of great sociocultural stress to the point where our anxiety gets in our own way, and because we're so distracted with our own shit, this can cause us to hurt others in our own interpersonal lives as a result.”

When Topside Press disbanded due to internal disputes between founders, Nevada went out of print and Binnie ventured into television writing. In 2016, her countercultural novel landed her in the writers’ room for Doubt—a CBS legal drama starring Laverne Cox. The series marked a watershed moment as the first broadcast network show with a transgender lead character portrayed by a transgender actor.

Between her television writing stints, Binnie received a request from Jackson Howard, an editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. A fan of Nevada, he requested new material from Binnie, but she had nothing that was fit for a book proposal. After meeting with a literary agent, however, FSG agreed to re-print her 2013 cult darling. “Every part of Nevada is uncompromising, most of all in the way that is explicitly not written to cater to a straight, or cis, audience,” Howard shared via email. “And yet within that framework, it's a universal story of belonging and growing up.”

Since Nevada’s initial debut, there have been great strides in bringing LGBTQ+ stories to the mainstream. Binnie expressed admiration for Janet Mock’s 2014 memoir Redefining Realness, which placed the trans activist in a “lineage of Black thinkers doing critical work” and challenged Binnie’s own preconceptions of what trans memoirs could accomplish.

“Nevada did not invent the idea that trans women should write about themselves. There were many that came before, and Binnie's novel came out in a time that was filled with a lot of trans women creating art about themselves in accessible and popular manners,” Valens says. “But what Nevada did was reach a group of trans women who didn't realize they could be written about realistically in fiction. All they had to do was pick up a pen and write.”

Though pop culture is filled with more trans and queer narratives than ever, there is still a lot of pressure to make LGBTQ+ art easily digestible, so that it can both educate outsiders and instruct the community’s youth. In Nevada, James doesn’t want Maria as their mentor, denying her an “aha” moment of catharsis. Even if anticlimactic endings aren’t for everyone, that may be this work’s enduring strength. Rather than prescribing self-love platitudes, Nevada encourages us to ponder how our past mistakes, experiences, and truths continue to shape us. It’s the type of lasting guidance Maria so desperately wants to give James: don’t stop adapting and learning; no one is ever finished.

“The response already has been so positive,” Binnie says in a final moment of reflection. “People are reading it and saying ‘Yeah, this is still doing the thing that it was supposed to do.’”

This article was originally published on