Joan Didion opens her legendary essay collection, The White Album, with “We tell ourselves stories to live.” So what can be made of a writer who lived off telling stories? To start, a sweeping catalogue. Throughout her career, Didion famously stretched her authorial limits, publishing everything from personal essays to cultural criticism and fiction.

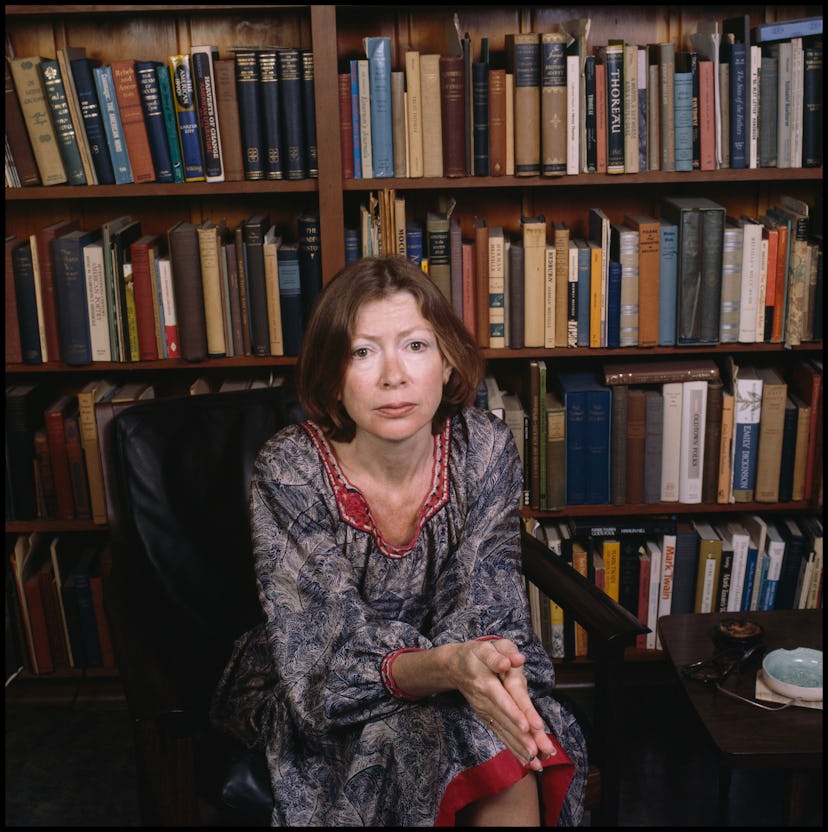

The enigmatic writer, who passed away in 2021 at the age of 87, continues to be a source of curiosity, luring readers with her bone-dry prose and uncanny ability to report on her life through a journalistic lens. Unlike some writers who, upon their death, journey into obscurity—their titles shriveling into backlists before ultimately falling out of print—intrigue around Didion has only flourished as the years go on.

Fanning these flames are a series of new releases and exhibitions. Last year, Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik was well-received by readers and critics, and just this March, the New York Public Library opened the Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne archive to the public. Now comes Notes to John, a book of Didion’s previously unseen journal entries addressed to her late husband, John Gregory Dunne. This is all wonderful news, of course. Any new Didion is a reason to celebrate—and read.

For some, the announcement of the book may derail the herculean exercise of identifying the right Didion for one’s current mind-set. We’re all just mood readers in the end, aren’t we? With no shortage of books to consider, it can be an undertaking to peruse her catalogue without time scurrying out under the door. Below is a distilled list of the best Didion books to read for your mood, headspace, or life chapter.

If You’re Moving…Or Feeling Homesick

Didion’s prose can scale walls, perhaps most profoundly when she’s revisiting the past. At once she maintains a cool reserve, returning to her home, her childhood, and her life, while delivering mundane experiences to significance—the color of the dress she wore for an eighth-grade speech, the glassy sugar of a cold Coca-Cola in the morning. While this may most profoundly be captured in her essay, “Goodbye to All That,” she returns to the topic of home nearly as much as she bounced between coasts, illustrating homesickness and the confounding longing for a place you’ve decided to leave.

In 1976, Didion traveled to San Francisco to cover the Patty Hearst trial for Rolling Stone magazine. The article was never published, but it sparked something in her: The need to reconsider her identity as a Californian. Collected in this gathering of notes, which will especially delight the aspiring journalist and writer, Didion shares her observations of how a place shapes a person, and how that person, in turn, settles into the landscape, carrying sunsets and local customs in their luggage. Admittedly, the California segment of this book is rather slim in an already brief book, but it marks an important turning point for the author. It ultimately led to the writing of a memoir about place, family, and belonging.

This was the result of the notes Didion collected in South and West. A legacy Californian, Didion began to rethink the mythology surrounding her family’s trek to her home state. In this memoir, she retraces her ancestors’s steps, pulling the thread on how much her identity has been cultivated by stories passed down through generations—her ancestors’s connection to the Donner party, the refusal to abandon a covered wagon that carried a personal library—and who she is without them. Where I Was From is a memoir as much about family heritage as it is the land where our upbringing occurs.

If You’re Going Through a Rough Patch

For Didion, few topics were off limits in her work. She covered everything from the peril of her marriage to the passing of her daughter. In interviews, the author declared that writing provided a way to make sense of her experiences. That, by putting them down on paper, she could begin to braid together the events and coincidences into something recognizable. When enduring an emotional time in your life, it can be a comfort to learn how others managed. These Didion titles provide light to peek around the edges of the challenges before you, providing company and solace.

The loss of a loved one never seems fair. But Didion received an especially tough hand. After visiting their daughter, who was critically ill in the hospital, she and her husband retired to their apartment for dinner. Once home, he suddenly died. Less than two years later, her daughter passed away. Didion’s memoir is a deliberate look at grief—at learning to process the sharp absence of her husband, and how to slowly heal from the acute heartbreak of losing him. Throughout this book, she sketches the lines of her grief, giving it shape and proportion, something to hold. For those who have lost someone, recently or otherwise, this book can serve as a companion, guiding the way through difficult days and joyous memories.

Perhaps motherhood requires existing in a chronic state of melancholy: mourning the baby stage, the infant stage, the stage before driver’s licenses and graduations and children of their own. Didion, of course, was granted a cruel vantage point to consider such concepts—outliving her daughter, who died at 39. Blue Nights is a time capsule of Didion’s life as a mother, from the early days after adopting Quintana to raising her, seeing her off to get married and then ultimately, her premature death. An unbearable loss, Didion lights the way for those in similar states of mourning, making sense of the incomprehensible.

It wasn’t all blue skies for Didion. Encountering several choppy years, the writer sought out support from a psychiatrist. Perhaps natural for a writer who’d been known to keep plenty of notes, Didion recorded these sessions in a notebook, addressing the entries to her husband. Increasingly, subjects of her sessions swung widely, shifting from her childhood to her career and their daughter. Didion has long been considered an enigma, her stoic persona seemingly unaffected by the turmoil knitted in her life. This book may well disprove these assumptions, illuminating some of her intimate reflections. For those curious on how she navigated difficulties and more, this new release is sure to satisfy.

If You’re In Need of a Cultural Refresher

Didion’s tightly coiled essays and novels often refracted large cultural shifts into the lives of her characters and interview subjects. Whether she was walking the streets of Haight-Ashbury during the Summer of Love or joining a recording session with Jim Morrison, Didion worked her way through the claustrophobia of the times by probing it, pen first. Now, decades after these books shook readers with their unblinking gaze and uncluttered prose, they serve as a key cornerstone from the era, exhibiting people in a country at odds with itself, arrested in stalled evolution. The themes, perhaps, have never been more prescient.

Touching on subjects of mental illness, motherhood, marriage, and a lostness that seemed to encapsulate the Sixties, Didion’s most notable novel continues to stun. Embodying the hollow glamor of the times, Maria is a former wife of a successful movie director, Carter. The two have parted ways for several reasons, the main one, however, being Maria’s purported breakdown. The book unfurls a collection of memories and recollections of what drove Maria to the brink of sanity: the glitterati and infidelity, plus her unwell child and her own upbringing in Reno, a windswept, empty place. Play It As It Lays portrays the tension of maintaining appearances, even while one experiences setbacks.

Tackling everything from The Doors to the Manson murders and California, always California, The White Album depicts the fettered disarray of the Sixties, a moment when culture was at once propelled by the chance to inflict progress, yet mired by a war many resisted—all while playing out to a soundtrack of thrumming rock and roll. Didion is at her finest here, distilling the panic of the times into a quiet drip whose source you can’t seem to place. Come for the Hollywood anecdotes, stay for the licked-plate prose and unwavering reporting.

“The center was not holding,” begins the title essay of this famous collection about the youth revolution in San Francisco, which for reasons unclear, had stumbled and landed facedown in the dirt. In this collection, Didion frames the horror—natural and manmade—that mottled the Sixties. While The White Album illustrates the movers and shakers and those bewitched by the promise of the American dream, Slouching Towards Bethlehem flips the era onto its back and examines its thick underbelly: the slippery politicians and burned-out youngsters, the directionless faces, carried on the thick Santa Ana winds that punish the California desert.

If You’re Disillusioned by Current Affairs

Much of Didion’s work is tinted with a political blush. From the above essay collections about the fractures within the country to novels that imagine the life of a senator’s wife, Didion has long turned her lens to the people pulling the strings. While current affairs are commonly framed as “unprecedented” and “never before,” Didion’s novels and essay collections reveal that these shadows are familiar with the halls of democracy.

Set in Boca Grande, a fictional country in Central America, two Americans, Charlotte Douglas and Grace Strasser-Mendana, collide. The latter—a wealthy widow who commands the small country’s economy—and former—a mother searching for her daughter who’s taken up with radical activists— might not think twice about the other if on home soil. Yet, in a foreign country, they recognize something in one another. Hemmed in by gender roles and social customs of the Sixties, the two engage in a knotty friendship that occurs at fund-raisers, country clubs, and the American Embassy. But a current churns through Grace’s infatuation with Charlotte, and as the search for her daughter ratchets up, Grace becomes an investigator of Charlotte’s life. What she finds looks familiar.

Narrated by a fictional “Joan Didion,” comes the story of Inez Victor, wife to Harry, a U.S. senator with presidential aspirations and Jack Lovett, the possible CIA man, with whom she is emotionally entangled. Spanning the late Sixties into the mid Seventies, Democracy is a story of shadow play. Didion—the real one—illuminates the tension between a politician’s high-gloss veneer and the darkness it conceals. It is also the story of a failed marriage, crumbling as Saigon, where much of the novel takes place, also falters amid the Vietnam War. It is also a story of war—of the violence contained in each of us, and the brutality that can leak out, which leads to devastating results should one have the power of an army behind them. Democracy delves into concepts of colonialism (Inez is a member of a white aristocratic family in Hawaii), intelligence, and power dynamics within relationships, both romantic and diplomatic.

At this moment in history, the gridlocked dance between media and politics has never been more evident. But this didn’t happen overnight. Didion’s collection, which features works published between 1988-2000, serves as a solid jumping-off point to understand present struggles. Untangling topics from Ronald Reagan’s presidency to the Monica Lewinsky scandal and post-Watergate Bob Woodward, Didion mulls the issue of press and politics, coming away with a sense of a toxic pas de deux that leaves both dancers limping.