Myriad ghosts of New York past are conjured in a trio of new books chronicling gritty city life in the 1970s and beyond. While all stylistically different, Guy Trebay’s Do Something, Cynthia Carr’s Candy Darling, and Tricia Romano’s The Freaks Came Out to Write offer complementary narratives, zig-zagging through legendary spaces—Max’s Kansas City, Caffe Cino, The Stonewall Inn—and conversing with the oddballs who made up New York’s creative milieu. Fittingly, there’s a continuous thread of self-invention—and reinvention—that connects Trebay’s anecdote-packed memoir, Carr’s poignant biography, and Romano’s “definitive history” of The Village Voice.

Do Something: Coming of Age Amid the Glitter and Doom of ’70s New York

Far from a fast-acting glitter bomb, Trebay’s memoir starts off on a reflective note, as the veteran reporter sifts through the ashes of his parents’ Long Island home in search of a suitcase filled with family photos. Once recovered, the images illustrate an untraditional childhood informed by fabricated narratives—including one about Trebay’s father’s successful cologne company, Hawaiian Surf.

“It goes without saying that no connection existed between my father’s invention and the complex social and cultural realities of Hawaii,” Trebay explains. “In an odd and coincidental way, I see now that this prepared me to come of age in Manhattan during a period when the city was populated by an awful lot of people whose sole driving ambition was reinventing themselves.”

Rebellious teenage years—riddled with skipping school, dropping acid, and shoplifting—gave way to finding his tribe in New York City, a group “composed primarily of people who thought nothing was more logical or essential than altering your name or biography or gender affiliation.” Before long, Trebay began to encounter—and closely observe—Warhol-adjacent personalities in haunts like Bogie’s, an East Village ragpicker’s paradise.

“Rummaging through the bins then you often found yourself scrabbling for treasures alongside Holly Woodlawn, not yet a Warhol star though well-established as a local character and garrulous speed ranter, usually smelling like a goat. … Occasionally, even Candy Darling turned up. … If I was drawn to people like Candy, it was because I shared her desire to metamorphose, without knowing into quite what.”

From 18 to 23, Trebay held an array of odd jobs including bussing tables at Max’s Kansas City (a gig he abandoned after discovering a half-eaten T-bone steak in a tub of vanilla ice cream) and collaborating with his artist friend Paula Hyman on a well-received accessories line named Frying Pan Ranch.

One day while casually stalking Greta Garbo, Trebay discovered something other than the elusive star: “pigeon pirates” capturing flocks of birds in a net—perhaps destined for a cockfight, a shooting range, or even a fancy French restaurant.

“Baffling as the episode was, and easy enough to slough off in a city where the inexplicable is an everyday occurrence, it awakened something in me,” Trebay recalls. “Without understanding it, I had found in the pigeon rustlers elements of a subject—New York City itself—and, by way of it, a profession.”

While “writing was not part of the plan because … there was no plan,” Trebay had started drafting scripts for plays he fantasized about staging Off-Off Broadway. Although he’d barely earned a high-school diploma, he’d learned invaluable life lessons from new friends like the Warhol Superstar Jackie Curtis. Trebay decided he “might as well give writing a crack” and called then-Interview editor-in-chief Rosemary Kent, who let him try his hand at profiles. “I feel like a fraud, of course, when I take on my first assignments,” Trebay recounts.

In 1976, Trebay landed a full-time job assisting Village Voice arts editor Alexandra Anderson. Initially tasked with editing “pithy snippets” about cultural events, he was soon working alongside staff photographer Sylvia Plachy on a weekly column dedicated to city life. “We share an ability to adapt quickly to whatever life throws at us,” Trebay says of his decades with Plachy. Curveballs included the Crown Heights Riots (during which they “were chased by an angry mob … before ducking in desperation into a beauty salon”) and an uprising in Romania (“reporting on foreign war zones … was not on my long list of life goals.”).

While still finding his way at the Voice, Trebay—who currently works for The New York Times—realized he had more interest in covering “oddballs and anomalies” than celebrities and socialites. Do Something is filled with passages dedicated to the likes of the Paris Is Burning star Dorian Corey—who played Scrabble with Trebay while her infamous mummy decayed in her closet—and Coney Island’s World in Wax Musée proprietor Lillie Santangelo, who lovingly sculpted “moonlight stranglers, despots, and two-headed babies.”

“There used to be a city filled with stories like Lille Santangelo’s,” Trebay says. “We don’t live there anymore.”

Brook Avenue, the South Bronx, 1988

Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar

Informed by diaries, interviews, and archives including the Jeremiah Newton Collection, Cynthia Carr’s biography Candy Darling paints a fascinating—if tragic—portrait of one of Warhol’s most enigmatic superstars.

Born in Queens in 1944, James Lawrence Slattery grew up in an abusive household in Massapequa Park, Long Island. Tortured by gender dysphoria, he considered his penis a biological “flaw.” Bullied relentlessly, he dubbed school “the snake pit” and avoided it at all costs. As an escape, he pored over movie magazines and imitated his favorite stars—Kim Novak and Marilyn Monroe among them—in the company of trusted girlfriends.

After dropping out in 1961 and earning a cosmetology license, Slattery began a metamorphosis involving hormone therapy, women’s clothing, makeup, and a new name: Candy Darling. But as Carr’s book reminds us, Candy didn’t identify as a drag queen—or a gay man.

In tandem with this reinvention, Candy began hanging out on Christopher Street—picking pockets and turning tricks if needed. A budding friendship with Jackie Curtis led her onto Off-Off Broadway stages to star in oft-improvised productions such as Glamour, Glory, and Gold and Vain Victory.

Before long, Candy had joined Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn as a favored member of Andy Warhol’s inner circle. Immortalized in Warhol’s radical feminist spoof Women in Revolt, the scrappy trio of Candy, Jackie, and Holly is among the most amusing threads in Carr’s book. “Sometimes we loathed one another and sometimes we loved one another,” Holly recounts. “We shared laughs, tears, makeup, and drugs. But when it came to sharing the spotlight, it was every broad for herself!”

Although Candy routinely passed as female, she had terrible teeth and was constantly losing caps at inopportune moments. “One night the three of them were at Ratner’s,” Carr writes. “Candy began stuffing her handbag with dinner rolls, then bit into one and lost what Holly called ‘the last tooth in her head.’” This telling snippet also speaks to the chronic poverty Candy faced—she was no stranger to sleeping on couches, stealing clothes from friends, and climbing out of hotel windows to skip the bill.

As Carr points out, the notoriously stingy and fair-weather Warhol was uncharacteristically generous with Candy, who was his poised and glamorous date to many parties and openings. Not only did Warhol occasionally pay for Candy’s hormones and dental work, he sent her a color TV when she was in failing health.

Like Trebay’s memoir, Carr’s book is brimming with anecdotes—detailing everything from Candy’s eccentric performance résumé to iconic photo shoots with Richard Avedon, Cecil Beaton, Francesco Scavullo, and Peter Hujar.

Poignantly, it also highlights Candy’s sharp, dry sense of humor. When the lump in her stomach—a tumor that led to lymphoma—became too big to hide, she told friends she was pregnant. And when Hujar came to photograph her on her death bed—fully made up, with a long-stemmed rose by her side—Candy displayed a talent she’d been perfecting for years: playing a dying movie star.

She was “camping it up,” Hujar later wrote. “Playing every death scene from every movie.”

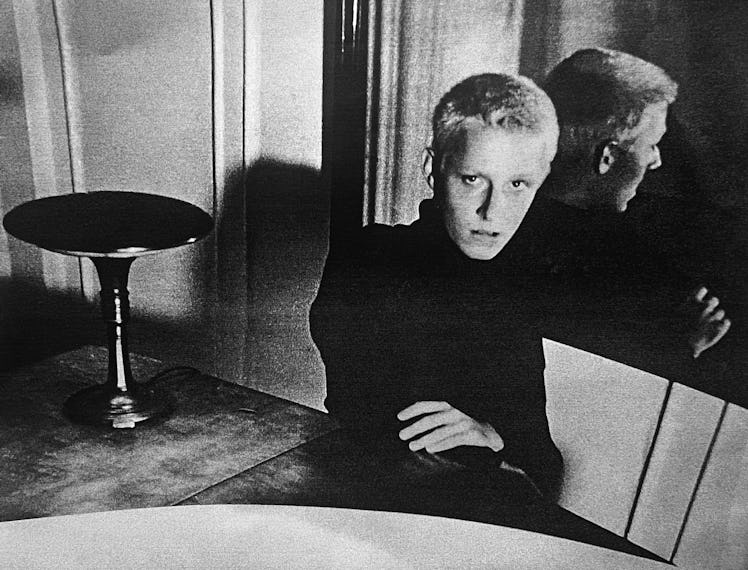

Candy's 29th birthday

The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of The Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture

A former intern who spent eight years writing for the Village Voice, Tricia Romano dives deep into the pioneering alternative weekly’s history with an ambitious 608-page volume divided into 88 chapters—her very first book.

Covering a broader time frame than Do Something and Candy Darling, The Freaks Came Out to Write begins with the 1955 founding of the Village Voice—by novelist Norman Mailer, editor Dan Wolf, and psychologist Ed Fancher—and stretches into the present day. It’s also a far less narrative affair due to its format: essentially a lengthy interview with—and about—an extensive cast of characters. Ringing in at more than 200 individuals, Romano’s cast is introduced but once, in a dedicated section populated by everyone from Voice legends like Vince Aletti, Lester Bangs, and Lynn Yaeger to convicted criminals such as club-kid killer Michael Alig and former U.S. President Donald Trump.

Pulled directly from conversations, Romano’s chapter titles provide a clear idea of what to expect: “You’re hiring all these Stalinist feminists.” “We’re against gentrification, and we’re for fist-fucking.” “We had a bomb scare once a month.”

Throughout the book, there’s a lot of shop talk—hirings, firings, leadership changes, feuds between staffers—that may only appeal to hardcore media nerds. But there’s also a wealth of candid accounts detailing the evolution of New York City and the Voice itself.

The book’s title is justified by accounts of unsolicited stories arriving at the Voice—some mailed in, some slid under the door. The paper also favored unseasoned writers. When he purchased the Voice in 1977, Rupert Murdoch told the staff, “I’m so glad to be in a place where no one has a journalism degree.”

With or without degrees, Voice writers rose to the occasion of covering everything from the Stonewall Riots to the blackout of 1977 to the AIDS pandemic to the birth of hip-hop. In the midst of it all, the Voice grew and changed, hiring its first female editor in chief, Marianne Partridge, in 1976 and making strides to employ Black and gay writers.

“The Voice that we knew? It really begins in the mid-’70s,” longtime contributor Greg Tate tells Romano. “Because it really was able to define the New York it was speaking to and for, that was not being spoken to.”

Exemplifying that practice is the Voice’s 1986 cover story on performance artist Karen Finley—penned by Candy Darling author Cynthia Carr. “L’Affaire Karen Finley!” details not only Finley’s food-centric provocations—such as her performance piece Yams Up My Granny’s Ass—but the public outrage Carr’s story elicited. “Suddenly, all these cans of yams were appearing in the office [on] people’s desks,” Carr recalls. “It was a little scary for me, actually.”

During that same era, Michael Musto began writing the Voice gossip ditty “La Dolce Musto.” From humble beginnings as a slender column accompanied by a tiny photo, it expanded into a two-page spread covering parties, nightclubs, celebrities and—importantly—drag queens like RuPaul. “I was the only one covering this, pretty much,” Musto says. “Now little kids are running around in drag, because they’ve seen Drag Race. I think it’s great. It’s the world I helped fight for.”

The cover story that caused the “great war.” C.Carr’s piece on performance artist Karen Finley, 1986.