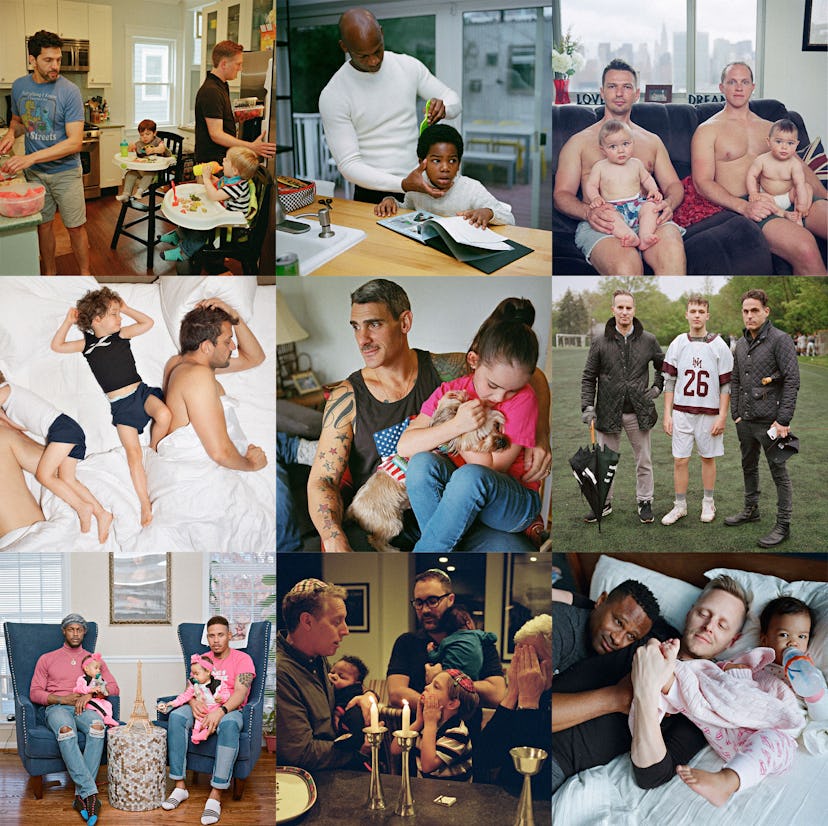

Bart Heynen’s New Book Dads Shows the Nuances of Gay Fatherhood

Welcome to Ways of Seeing, an interview series that highlights outstanding talent in photography and film—the people behind the camera whose work you should be watching. In this week’s edition, senior content editor Michael Beckert chats with the photographer Bart Heynen, whose new book Dads is now available. Below, the photographer shares his experiences fathering two children with his husband, and what he learned from traveling the U.S. to take pictures of other gay dads.

Where did you grow up? How did you get into photography?

After high school, I went to school to become a movie director in a town called Leuvin; it’s a well-known university town in Belgium. After a while, though, I realized that filmmaking is very team-dependent, and I’m an independent person. Soon after that, I switched to photography, which I felt more comfortable with—you have a much smaller crew, and you still have everything in-hand. I did a postgraduate at ICP in New York, and I really loved it—I learned all about strobes there, and shooting with slow shutter speeds with film. Before I became an independent photographer full-time, though, I actually worked as a film producer for television. I liked it, but it was incredibly intense, and pretty insane. In television you’re working 18 hours a day, and you’re barely paid, but you get a ton of responsibility early on.

How long were you shooting the images for Dads?

It’s been four years in the making, and I did it while I was doing my other commercial work. It’s a really long time, if you think about it—that’s the duration of Trump’s entire presidency. It’s my favorite project yet. Everyone says that about their latest project, but I really mean it. As a gay dad, this one is really close to my heart. I didn’t know a lot of other gay dads before starting this project.

What was your process like, shooting the families?

I’d bring my kids along sometimes so they could meet other gay dads, which ended up being a great ice breaker. I felt an instant connection with most of these families, though, because you share this bond with one another—this same plight in life. For some of the families, I’d visit them three or four times. Sometimes, after just one session, you don’t have the picture yet.

Dennis combing Élan’s hair. Brooklyn, New York © Bart Heynen from 'Dads' published by powerHouse Books.

Your book made me reflect on the fact that, in my own experiences meeting other gay guys my age, not many of them talk about aspiring to be parents one day.

I remember when I was your age, I saw on the cover of Newsweek a family of two guys with their kids, and it gave me such a “wow” moment. I was living in Belgium at the time, and people couldn’t even get married there at the time, so I was really amazed. It meant so much to me.

Of your other gay male friends who are in relationships, are any of them outspokenly opposed to becoming fathers?

Many of my friends said “No way, I don’t want to get kids.” When I was in my twenties, I wasn’t super interested in the idea—my husband got me thinking about it. I have to tell you, though: the first two years of parenthood were very difficult and I wasn’t super happy. We had twins, so it was a lot to take on right away. My husband and I had decided that he’d continue working and that I’d take time off for a year. Suddenly I was going to the park every day with my two babies, surrounded by nannies and new moms. Everyone was straight, so I felt particularly weird. Nowadays, I can’t imagine my life without my two children. They’re the best thing that ever happened to me. But when you’re used to a gay lifestyle where you can do whatever you want, it can be a major adjustment.

Did any of the subjects from your book talk about a specific pressure on gay dads to be absolutely perfect parents?

In my own experience, I didn’t feel that pressure, but I did discover that suddenly I was surrounded by so many women who wanted to help out. It was great, but at a certain point I was like “I got it, don’t worry. I can do it.” Even now, we’ll be on vacation, and there will be a woman who sees my husband and I, and she’ll sort of look at us and think “My husband would never be able to do that,” so she’ll come up to us and offer some help, which is very sweet of course, but you’re basically always getting extra attention. For some of my gay dad friends, it’s overwhelming and makes them feel crazy. They feel like, “Do you not trust me to do this?”

Harrison and Christopher with their daugther Genhi. Brooklyn, New York © Bart Heynen from 'Dads' published by powerHouse Books.

Me and Rob with Ethan and Noah at 630 AM. Antwerp, Belgium © Bart Heynen from 'Dads' published by powerHouse Books.

Was your family accepting when you came out, and also when you decided to have kids?

Coming out is a huge thing in America, but less so in Belgium and Holland. These were the first countries in the world that legalized gay marriage. I told my parents when I was 17, and it was pretty scary. I was in the kitchen and they were in the living room, and I told them without making eye contact. I couldn’t even be in the same room as them. This was during the AIDS epidemic, so my parents were more worried than anything else, but now they’re so happy they have grandchildren. My mother is 86 and she calls every day to talk to the kids. One of the best things about being gay dads and raising kids, is that we bring children into a family where there is no more coming out. My kids would not need to make a big deal about being gay or straight. They can have a boyfriend or a girlfriend or whoever, and I think that’s such an enrichment all on its own.

Where did you travel in the United States to shoot this book.

I started in New York City for the first two years. I was looking for more [stereotypically] American families, so I realized I’d have to travel elsewhere. I went to Utah and Omaha, Alabama, all over. I found there’s a big difference in acceptance depending on where the family is living, but how the family lives its life is pretty much the same all over.

What is it like for gay dads in Utah?

I photographed two families from Utah. One is a single dad who was married, but divorced his ex-wife and stepped out of the church. He also had children with her, so he had to come out to his kids. This other couple I photographed there also grew up in the Mormon church, and what was most interesting is that, when speaking with them, you can tell the church is still such a big part of who they are. But it’s difficult because eventually, you have to choose between being openly gay and keeping the friends and community you formed in the church. Being who you really are comes with a major sacrifice in that community.

Which other families stood out to you?

I photographed a family in Omaha, Nebraska who did not have the financial means to start their family, so one of the guys asked his mother to carry the baby—and she said yes! She thought it would never work, because she was 60 years old, but her doctor gave her the green light. The other man in the relationship asked his sister to be the egg donor, so it was really a unique and beautiful way to create a baby.

Did anyone say no to being photographed?

Very few. I think they all felt united in the effort to help visualize this part of human existence, especially for their kids. They’re proud of their families and they want people to see what this looks like.

In your own experience, did you feel pressure to choose adoption over finding a surrogate or vice versa?

I didn’t, really. But I did feel strongly about not having a situation in which we used my DNA for one kid, and my partner’s DNA for another. I felt that would create this strange feeling of, “This is my biological kid, and this is yours.” I wanted us to feel like one family, and even though we used my partner’s DNA, these children are also mine.

What’s your favorite picture in the book?

One of my favorites is of two men sitting so proudly in their home, and their child in the middle is yawning. I love that one. The child is underwhelmed by the pomp and circumstance of it all—it just knows that it’s loved.

Patrick and John with their daughter Mila at Home in New York City. © Bart Heynen from 'Dads' published by powerHouse Books.

What is the most unique thing about being a gay dad?

Probably the start, when you’re suddenly a caregiver. That felt really different for me, and somehow—even if this isn’t an okay thing to say—it felt like a challenge toward my masculinity. Now, I would never say I feel that way. But back then, I learned that you shouldn’t have one dad do all of the caregiving—you should interchange the responsibilities at the start. In my instance, we didn’t do that. But after talking to so many gay dads while making this book, I realized that’s what most of them are doing.

What advice would you give to younger artists starting out?

Take a subject matter that interests you and is part of your life. Make work about that, something that’s close and important to you. Also, only buy one camera and one lens, and stick to it for at least a year before you try something else.

This article was originally published on