Prematurely Plastic

Cosmetic procedures are meant to turn back time, not speed it up. Rob Haskell reports on a new breed of beauty junkie, whose goal is to look forever 36—even if she’s 23.

In October of last year, Lindsay Lohan unveiled her first, and only, ready-to-wear collection as the artistic adviser of French fashion house Emanuel Ungaro. She had been hired to scatter a bit of youthful insouciance upon a label that, in its Seventies heyday, had taught the ladies of the rue de Grenelle how to wear fuchsia. But after the last set of sparkling, heart-shaped pasties shimmied offstage (their final resting place very likely not the Ungaro archives), Lohan took to the runway and presented what may have been the afternoon’s most shocking look: her face.

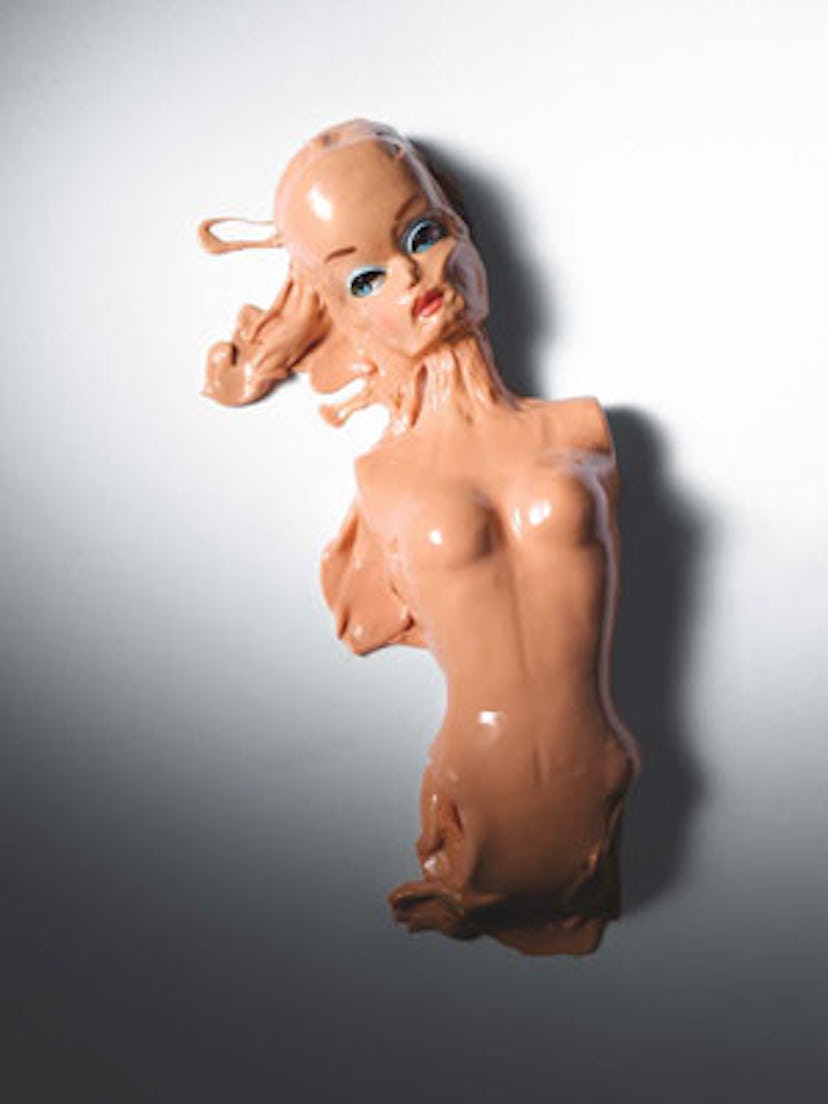

It’s a face that has become all too familiar of late: the lips seemingly flipped up and flattened like soggy hamburger buns; the taut, shiny cheeks that look like they’d been kept at higher pressure than an Icelandic volcano; the monolithic forehead, girded with hair the color of sunlight hitting chrome. Surely Lohan’s aim was to preserve the pert, plump architecture of youth, with its even surfaces and apple-y convexities. But the result was just the opposite: Lohan, then 23 and not yet a convict, appeared to have found her way to that effortful, worked-on face that used to be the consolation of women two or three times her age.

Philip Miller M.D. is convinced that Lohan, in the tradition of her biologically ageless forebears Heather Locklear and Madonna, has swilled an elixir that even the best DNA can’t duplicate. While none of the women have admitted having plastic surgery, Miller has a different opinion: “Those women have all had something done,” he says.

They’re not alone. In Hollywood, on the Upper East Side, and in one-dermatologist towns all over America where girls aspire to be contestants on The Bachelor, the precocious use of Botox, fillers, implants, and all manner of nips and tucks is making young women look…old.

“It’s a matter of the right procedure on the wrong girl at the wrong time,” says New York plastic surgeon Douglas Steinbrech, who has seen the average age in his waiting room fall like a sexagenarian’s jowls. “There’s this new mentality that if you do not look a little bit fake, then the surgeon hasn’t done his job. This used to be a much more prevalent idea on the West Coast, but now you walk up Madison Avenue, and you see these young girls with that cloned, cougarlike face. Either they don’t know what they look like, or they want to look like they’ve had something done.”

In fairness to Lohan and her ilk, that something usually isn’t surgery. Botox abuse is the No. 1 culprit: too much, and in too many places. Fillers—Juvéderm, Restylane, Sculptra, Radiesse for that particularly bulbous effect—run a close second: lips, cheeks, eyes, temples, liquid nasal reshaping. For the brave, there are implants: Chin and mandible are just the tip of the silicone iceberg.

“Filler is like heroin to a junkie,” says Miller, Steinbrech’s partner at Gotham Plastic Surgery. “It’s easy and available, and for that second hit, you might find yourself wanting a little more.” It’s the job of professionals like Miller and dermatologist Gervaise Gerstner to say no when a patient’s eyes are quite literally bigger than her stomach. “Filler’s become a lunchtime thing,” Gerstner says. “And now you have these people getting carried away with the chipmunk cheek. That, plus the big white fake teeth and the thin, straggly old-lady hair that’s the result of Brazilian blowouts, bleaching, and the flat iron, and you can very quickly end up looking like your mother.”

But today’s addicts are not members of Generation Cher, seeking merely to turn back time. Even Jocelyn Wildenstein must have noticed that “plastiholism” has a new face—and new F-cups—in Heidi Montag, a star of the reality-TV series The Hills. Montag, who is 23, underwent 10 procedures in a single day last November, and though she claims she nearly died from a Demerol overdose and has conceded that her new body makes “hugging” and “jogging” difficult, she continues to preach the gospel of the scalpel. (“If Cleopatra were alive right now,” Montag recently told Billy Bush, “I’m sure she’d have triple Ds.”)

In fact, cosmetic procedures are as ancient as the pharaohs: Descriptions of nasal surgery have been found in hieroglyphics, and physicians in India experimented with skin grafts to repair facial injuries as early as 800 BC. The arrival of general anesthesia in the mid-19th century ushered in a golden age of medical discovery, and in 1887 American surgeon John Orlando Roe performed the first nose job. A few years later surgeons injected paraffin into breasts to make them larger; when this failed they turned to implants made of glass and ivory. Plastic surgery techniques made giant gains during World War I, when doctors were called upon to repair the battered faces of returning troops. It didn’t take long for the vain to make use of these innovations. In 1923 Ziegfeld Follies star Fanny Brice underwent a procedure to change her nose from “prominent” to “merely decorative.” At around the same time, in Paris, French novelist Colette had a primitive facelift in her efforts to seduce Bertrand de Jouvenel, her 16-year-old stepson.

Today’s tweaks look dramatically better and are easier to come by, which, according to dermatologist Amy Wechsler, is precisely the problem. “Too much or too often, and you get that frozen, deer-in-headlights look,” says Wechsler, who believes that young women begin to look older than their years when they turn to Botox and fillers but continue to run their skin through a wringer of sun, cigarettes, alcohol, stress, and lack of sleep. “It’s like they’re re-draping dirty curtains,” Wechsler says.

To the lay observer, however, it’s the lips that don’t lie. But if that overly pillowy profile, which Mother Nature doles out parsimoniously, is so obvious, then why are young women buying it at $850 per syringe? (It can take four needles’ worth of Restylane to achieve Angelina Jolie–like fullness.) Three explanations present themselves. First, there’s our increasingly youth-obsessed celebrity culture, which has lately offered the lushly adolescent contours of Miley Cyrus; they may be enough to make even Lohan feel over the hill. Then there’s what psychiatrist Robert B. Millman has called acquired situational narcissism: that disorder of identity afflicting billionaires, movie stars, and politicians, whose obliging entourages do little to keep their weaker impulses in check.

Finally, there’s the matter of status, the impatient spirit that inhabits no Louis Vuitton bag for very long. Given the mainstreaming of designer clothing and accessories, and the ubiquity of compelling counterfeits, it’s not clear what a girl ought to do these days to show the world how rich she is. “It used to be about borrowing your mother’s old Birkin,” says John Barrett, the hairdresser whose salon atop Bergdorf Goodman is the scene of a daily parade of women for whom the word “overworked” has nothing to do with being employed. “Now it seems to be about borrowing Mom’s plastic surgeon. It’s kind of like a very perversely sophisticated game of dress-up.”

At SoulCycle, a spinning studio on East 83rd Street, the game of dermatologic dress-up is in full swing. The women alighting from chauffeured black Escalades look like an army of ocher jack-o’-lanterns; the 15-year-olds (there for the popular teen class) not always easy to tell apart from their 51-year-old mothers. Jill Kargman, author of the forthcoming essay collection Sometimes I Feel Like a Nut, believes that some of the cosmetic extremism on display is an extension of the fitness obsession—and perhaps a consequence of it, since skinny thighs equal sunken cheeks.

“Surgery’s the new working out,” Kargman says. “People see it as maintenance, like getting a bikini wax. You hear about boobs courtesy of Dr. Hidalgo as graduation presents from private school, where it used to be just nose jobs for your bat mitzvah.”

And yet for all these little Faye Dunaways in training, there has never been a better time to fight the crepey creep of years. Those who succeed achieve a look that, if not ageless, is at least the right age: about 36. “Some people wake up at 42 and realize they need to return to 36,” says Gerstner. “But the people who end up looking best have been planning for it all along.” She believes that the fountain of eternal thirtysomething can be found in measured doses of Botox, filler, and Fraxel—a very expensive sandblaster for the skin—and with maintenance in the form of glycolic peels and Retin-A.

When it works, the effect is staggering. Demi Moore, who has publicly acknowledged entrusting some aspects of her upkeep to modern medicine, has looked 36 for the past decade. If she’s careful, she’ll be 36 for another. At New York’s swirl of uptown parties, a handful of socialites nearing the midcentury mark have been looking beautifully 36 for a while now. Whether that’s by dint of good genes or stealth visits to Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat is anybody’s guess—which is precisely the point. For Lohan, on the other hand, the only guessing game is why a woman who has not yet celebrated her 25th birthday should aspire to a face fit for blowing out a dozen more candles.