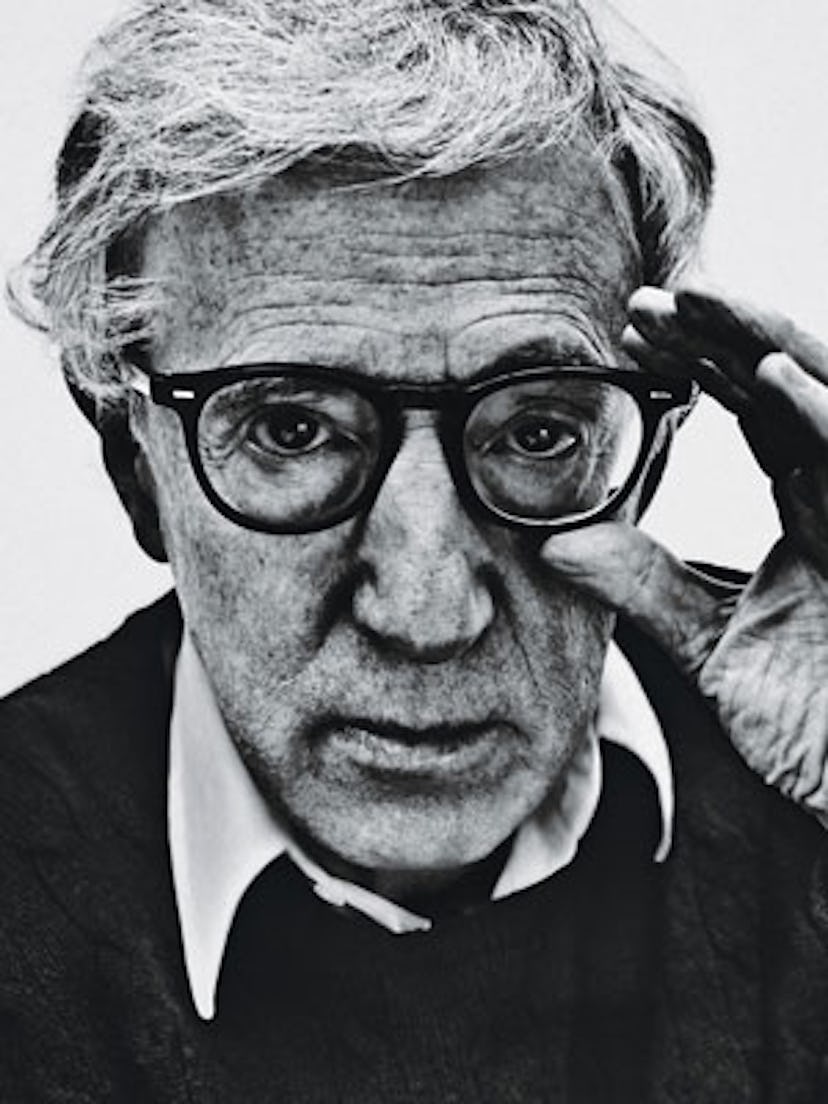

Woody’s Women

On the occasion of his 11th showing at the Cannes Film Festival—Midnight in Paris, starring Rachel McAdams—Woody Allen reflects on 40 years of movie muses.

In nearly every Woody Allen movie, from Bananas to Midnight in Paris, which opened this year’s Cannes film festival, there is a central male character who’s a facsimile of Woody Allen (neurotic, brainy, urban). And, like a sun encircled by planets, Allen surrounds his cinematic twins with a constellation of fascinating, beautiful, and unique women. While the Allen men are consistent and familiar, his female characters are surprising—they defy the industry standard of one-dimensional moms, babes, or best friends. In his 11 showings at Cannes, the 75-year-old director has introduced such striking and diverse characters as Mariel Hemingway’s precocious teenager in Manhattan; Scarlett Johansson’s seductive and doomed would-be actress in Match Point; and Penélope Cruz’s crazy, enticing Maria Elena in Vicky Cristina Barcelona. Allen was clearly inspired by Mia Farrow, and her versatility in his Cannes films—from brassy blonde in Broadway Danny Rose to innocent time traveler in The Purple Rose of Cairo to unofficial matriarch in Hannah and Her Sisters—is remarkable and has unfortunately been overshadowed by their personal turmoil. In the end, although the work endures, Allen quickly moved past Farrow: He has, seemingly, no shortage of muses. In this year’s Midnight in Paris, he tweaks Rachel McAdams’s good-girl image, reimagining her as a socially ambitious, fast-talking nag. “I wanted her to play the bad girl, the girl who’s sexy enough to be negative and still interesting,” Allen told me over the phone this spring. “But I’m crazy about Rachel. I have great adoration and lust and interest in all of the women in my films. It would thrill me to go out with all of them.”

As a former stand-up comedian, Allen initially wrote his scripts for himself. “I was the male,” he explained. “And I played the lead. I never used to be able to create parts for women. But then I met Diane Keaton, and we started dating and moved in together, and I started writing for her. She had a huge influence on me. Keaton has that large, large personality: I’d write the jokes for my character and she’d get all the laughs. By the time I got to Annie Hall, I was more comfortable writing for women than for men.”

Since Allen hates holding auditions, he spots most of his actresses in other movies. “Casting is so awkward,” he said. “I’m too shy to meet them. I have the women come in and I don’t let them sit down. I make up some questions, but I couldn’t care less about chatting. I only see them to make sure that they haven’t gained 200 pounds or had five face jobs. I want to see that the woman I saw on the DVD is still intact.”

He had, for instance, loved McAdams’s performance in Wedding Crashers, and kept her in mind for a future project. After watching Cruz in Volver, he created the part of painter Maria Elena in Vicky Cristina Barcelona specifically for her. “Woody and I had a meeting in New York for 40 seconds,” Cruz told me. “And when I left, the people who worked in his office said, ‘Oh—you have been there for a very long time.’ He said he had seen Volver and that he was writing a character that would be right for me. I love a lot of things about Woody, but I really love his honesty and that there is no social bullshit. He only talks to you about what he thinks is important.”

From an actress’s films, Allen seems to get a vision of her potential. “He cast me in Manhattan after seeing me in Lipstick,” Hemingway recalled. “And no one saw that movie. My last name is Hemingway, but I’m really a country girl, and when Woody called our house in Idaho, my mom had to explain to me who Woody Allen was. I had seen Sleeper, but, frankly, I thought it was the weirdest movie. I was freaked out by the egg in the film. But I still went to New York to audition. I read for him and I was terrible, but he saw something in me. I was 16 when I made Manhattan, 17 when it came out, and 18 when I was nominated for an Academy Award for my performance. It was like a dream.”

In Manhattan, Hemingway plays Allen’s much, much younger girlfriend. I asked her if it was strange being the object of desire of an older man. “There is that,” she said. “My first real make-out session in my life was with Woody in a hansom cab in front of a camera crew. Before the scene, I practiced making out on my arm in front of the mirror. After we had done the scene once, I said to the cinematographer, Gordon Willis, ‘We don’t have to do that again, do we?’”

But true to Allen’s prescient sense of complexity, Tracy, Hemingway’s character, was not just a bimbette living in a man’s margins. She was sophisticated, wise, and, finally, more thoughtful than her older lover. “In real life, Woody and I didn’t have a romantic relationship, but he did make me feel incredibly intelligent. He took me to museums and concerts. He gave me his wisdom, and you can see that in the character.”

Allen maintains that a kind of romantic infatuation—a crush, of sorts—is crucial to his creation of the women in his movies. “For instance, I didn’t know Penélope from a hole in the wall,” he said. “But when she came into my screening room, I was stunned: She was even more beautiful than in the movies. She didn’t have to say a word, but I knew: I wrote the part for her, and I never saw anyone else.”

Maria Elena is one of the most enigmatic of Allen’s many diverse heroines. She is the ex-wife of a lothario played by Javier Bardem, and despite the fact that she tried to kill him, he is still under her sway. “I didn’t want to treat Maria Elena as a crazy person,” Cruz explained, “but one of the amazing things about Woody is that he can laugh at human pain and confusion. Often, you feel guilty about laughing at those characters. When I saw the movie with an audience in Cannes, I said, ‘Why are they laughing? This is not funny. All these characters are suffering so much.’”

Cruz, who won an Oscar for her portrayal of Maria Elena (Woody’s women have received a staggering 11 Academy Award nominations and five Oscars), will be working with Allen again this summer in Rome. “I had so much confidence in Penélope,” Allen continued, “that I let her and Javier Bardem improvise in Spanish in Vicky Cristina. To this day, I have no idea what they were saying.” Allen paused. “But I knew it was okay—I had her speak in character. The women, especially, in my films have to be real. And yet it’s also very important to me to present the women with the enthusiasm and eroticism and awe that I feel about them. I’m very concerned with how they look, that they match my image of them. In Match Point, I reshot the scene where the audience first sees Scarlett four different ways. I wanted it just right: the hair, the color and style of her clothes, everything. I wanted the audience to feel what I felt about her.”

Allen will fixate on an actress for years, imagining her in different scenarios, before he casts her. He longs to work with Cate Blanchett (“so funny in The Talented Mr. Ripley”) and Reese Witherspoon (“but it has to be a great part to be worthy of her”). “I wanted to work with Naomi Watts for a long time,” he said, “and then I cast her in You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger as the discontented wife of a philandering husband. And she was very funny and very sexy. For years, I loved Téa Leoni from Flirting With Disaster. I’m very critical of my own work, but Hollywood Ending did not get the audience it deserved.” In that film, Allen plays a director who suffers from hysterical blindness, and Leoni is his Hepburn-esque studio-executive ex-wife who guides him through the making of his film. Along the way, they fall back in love.

Like many Allen heroines, Leoni is quite tall. Historically, a leading lady would never be taller than her opposite: Allen’s casting of himself forever altered the image of what constitutes a romantic lead. He made nerdiness and a kind of twitchy intelligence sexy. “Keaton and I are actually the same height, but I don’t really mind when they’re taller than I am,” Allen said, shrugging off any notion of male vanity. “But in Manhattan Murder Mystery, I did make certain that Anjelica Huston was sitting on the sofa for our kissing scene. She’s at least a head taller than me, and if we were standing I’d be kissing her navel.”

When speaking about his actresses, Allen is almost dreamy, as if these women—his women—were permanently in a film that was always screening in his mind. “People say that my Manhattan is a fantasy Manhattan,” he said, explaining his romantic perspective. “And that’s correct. My concept of Manhattan is one that I gleaned from Hollywood movies. And it’s the same with the women in my films: I see them all through rose-colored glasses.”

Woody’s Women

“I’m crazy about Rachel,” said Allen of the star of this year’s Midnight in Paris. “I have great adoration and lust and interest in all of the women in my films. It would thrill me to go out with all of them.”

“I wanted to work with Naomi Watts for a long time,” the director said of his leading lady in You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (Cannes 2010). “She was very funny and very sexy.”

“I didn’t know Penélope from a hole in the wall,” Allen said of the star of Vicky Cristina Barcelona (Cannes 2008). “But when she came into my screening room, I was stunned: She was even more beautiful than in the movies. I wrote the part for her, and I never saw anyone else.”

“For years, I loved Téa Leoni from Flirting With Disaster,” said Allen. “I’m very critical of my own work, but Hollywood Ending [Cannes 2002] did not get the audience it deserved.”

“My first real make-out session in my life was with Woody in a hansom cab in front of a camera crew,” said Hemingway of her pivotal moment in Manhattan (Cannes 1979) at age 16. “After we had done the scene once, I said to the cinematographer, ‘We don’t have to do that again, do we?’”