The Castle Diaries

William Fiennes’s latest book evokes his not- always-cheery childhood at Broughton Castle.

When writer William Fiennes describes his childhood, it sounds like a hair-raising cross between The Hardy Boys and Eloise. Fiennes, 38, grew up at Broughton Castle, the ravishing Oxfordshire manor that has been in the family for more than 600 years and has boasted such guests as James I and Edward VII. He learned to ride his bike in the Great Hall, zooming around refectory tables while his mother, Lady Saye and Sele, oiled the suits of armor on permanent display there. He whiled away his summers swimming, rowing and fishing for perch in the castle’s moat and trying not to make eye contact with the portraits of his ancestors in the Long Gallery because they frightened him so much.

Fiennes’s youth was unusual in other ways, too. As he was growing up in this storybook setting, his family was dealing with the rampages of his eldest brother, Richard, an epileptic who suffered brain damage after a series of seizures. Eleven years older than William, Richard was a smart, sensitive boy, but his brain lesions would often cause violent outbursts: He once burned his mother’s cheek with a cast-iron frying pan, held a fork to his father’s throat during a meal and smashed windows with an iron bar on another occasion. Over time he became more aggressive, constantly testing the family, including William’s elder twin siblings, Martin and Susannah. Memories of castle life—and of Richard, who died in 2001—are the foundation of Fiennes’s most recent literary endeavor, The Music Room (Picador), which lands at American bookstores in August.

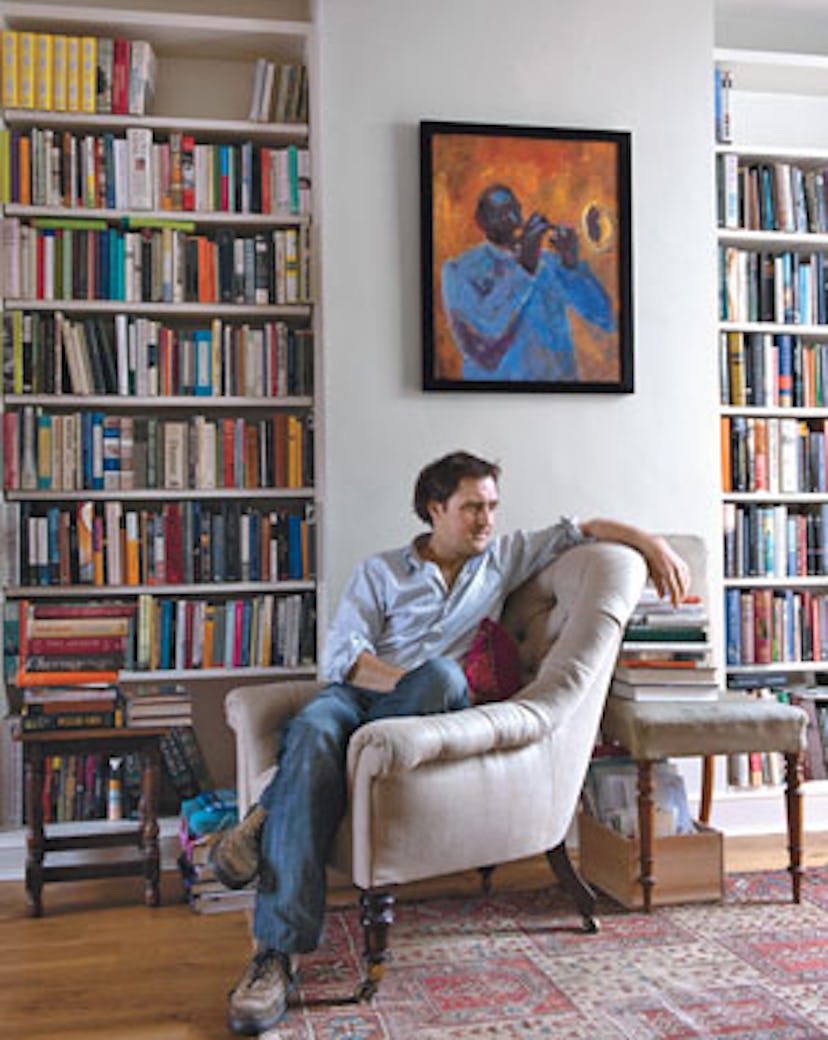

“We were basically an ordinary family in an extraordinary place,” says Fiennes, a cousin of actors Ralph and Joseph Fiennes, over a cup of tea in South Kensington. The soft-spoken writer, who has arrived today in a crumpled blue cotton shirt and jeans—his battered bicycle helmet under his arm—credits the castle for helping his parents cope throughout the years. “I think they were always strengthened by having something bigger than themselves to be involved in,” he says of Lord and Lady Saye and Sele, whose title, a combination of a family name and a town in Kent, dates from 1447. They still own and maintain the property and rent it out for such film productions as Shakespeare in Love. In the book, Fiennes recalls spotting his father after a particularly difficult day, standing next to the castle with his head down and his palm pressed against one of the buttresses. “He said he was asking the house for some of its strength,” writes Fiennes.

The Music Room, he says, is “meant to be a kind of song or poem,” a tribute to the manor and to Richard; its quiet, meditative mood is similar to that of The Snow Geese (2002), Fiennes’s best-selling debut about the birds’ migration and the concept of homesickness. In between penning critically acclaimed books, Fiennes, a graduate of Eton and Oxford, is writer-in-residence at the American School in London. He is also cofounder of First Story, a charity that recruits authors to teach writing courses in several state schools in England.

Fiennes, who lives alone and is currently single, admits he’s “a bad combination of shy and choosy.” And although he may be pals with cousins Ralph and Joe—“They’re both real thinkers,” he says—Fiennes confesses that he’s not working his formidable connections to take The Music Room to the big screen. But wouldn’t Joe be great in the role of William? “Ugh!” says Fiennes, rolling his big blue-green eyes. “Pass the sick bag. That’s waaay too many Fienneses.”