How Will Designer Willi Smith Be Remembered?

Though Willi Smith was one of the most liberated—and successful—American designers of the 1980s, his legacy has been practically forgotten. A new book and retrospective aim to correct that.

When Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, the curator of contemporary design at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, set about organizing a show on the late fashion designer Willi Smith, she found no shortage of material. There was footage of Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane’s 1984 dance piece Secret Pastures, for which Smith designed the striking costumes. There were renderings of the urban decay–themed showroom that the architecture and environmental arts studio SITE designed for Smith—it featured scavenged chain-link fences, pilfered NYFD fire hydrants, and all manner of half-demolished construction debris. There was Expedition, the film that Smith shot in Dakar, Senegal, with the photographer Max Vadukul, featuring locals, dancers, and Smith himself decked out in hot pink dashikis, pastel suits, and serious statement jewelry. And there were copies of The WilliWear News, the kooky fashion newspaper that Smith produced with his friend the Paper magazine cofounder Kim Hastreiter. The only thing missing? The clothes. “When we approached Willi’s friends and fans about borrowing pieces, we kept on hearing versions of the same thing over and over again,” says Cunningham Cameron. “They loved Willi’s clothes so much that they wore them all the time—so much that they’d turned into tatters. They literally wore them out.” And that’s just what Smith intended.

Smith, who died from AIDS-related complications in 1987 at the age of 39, was, in the truest sense of the word, a streetwear designer, long before anyone used the term. Even as he was collaborating with some of the most avant-garde artists of the day and staging fashion shows that doubled as performances, he was taking his cues as a designer from the women he saw on the sidewalks of midtown. “If Willi was inspired by something I was wearing, he would literally take it off of me,” says the model turned activist Bethann Hardison, who was Smith’s best friend, muse, and occasional assistant. And even as a Coty Award–winning designer doing $25 million annually in sales, he never got over the thrill of spotting one of his creations in the wild. “We’d be walking along and he’d say, ‘Oh my God! That person is wearing my jacket,’ ” recalls James Wines, the founder and president of SITE. For Smith, the woman in the street was both his inspiration and his intended audience. “Willi once said that he didn’t do clothes for the queen,” says Laurie Mallet, with whom he founded his label, WilliWear, in 1976. “He did clothes for the people who lined up to wave at her.”

Looks from Sub-Urban, Smith’s fall 1984 collection for WilliWear.Photography by Max Vadukul, Bill Bonnell papers, Vignelli Center for Design Studies, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY.

Smith was born in Philadelphia in 1948, the son of an ironworker and a homemaker. A bookworm, he studied drawing at Mastbaum technical school and, later, fashion illustration at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art. His big break came through, of all people, his grandmother Gladys Bush, who worked as a housekeeper. One of her clients had a connection to the famed couturier Arnold Scaasi and secured an internship for Willi. Though Smith assisted Scaasi in creating impeccably fancy looks for the likes of Brooke Astor and Elizabeth Taylor, and received a crash course in the art and science of the high-end atelier, the job was ultimately most useful in allowing him to recognize, as he would later put it, “the clothes I didn’t want to make.”

A WilliWear look from the fall 1984 collection.Photography by Max Vadukul, Bill Bonnell papers, Vignelli Center for Design Studies, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY.

Smith enrolled at the Parsons School of Design in 1965, armed with two scholarships and a prodigious talent that quickly attracted attention. By day he was pinning and draping, and after hours he was immersed in the radically experimental art scene that was beginning to put SoHo on the map. When he was expelled from Parsons two years later—allegedly for having a romantic relationship with another male student—he teamed up with fellow creative rebels Christo and -Jeanne-Claude on what would be his first of many art-fashion mash-ups. In -collaboration with the couple, with whom he’d work again on their famous wrapping installations of Paris’s Pont Neuf and 11 islands in Miami’s Biscayne Bay (Smith did the workers’ uniforms for those buzzy happenings), he constructed The Wedding Dress, a garment that resembled a mod tankini yoked via silk ropes to what looked like an enormous bundle of laundry—a housewife’s burden made plain.

Smith on the set of his 1985 fashion film, Expedition, which featured the Spring 1986 WilliWear collection in Dakar, Senegal.Courtesy of Mark Bozek.

Smith would keep one foot in the art world for the rest of his life, commissioning Nam June Paik and Juan Downey to create video installations for his fashion shows; teaming up with Keith Haring and other artist friends on a series of T-shirts; and crafting a grid of flat, white plaster “clothes” for a show at MoMA PS1. “He knew and worked with everybody in that sort of post-pop landscape,” Wines says. “And he had this really collaborative spirit, which at that time was really unheard of. Now everybody is trying to do it.”

An M&Co. postcard for WilliWear, 1987.Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution

At the same time, however, Smith was very much focused on the idea of clothing as a business, in the old-school, Garment District, schmatte-trade sense of the word. “You all can call it fashion, but we never really used that word,” says Hardison of Smith’s professional output. “Every duck and every cockroach is in ‘fashion’ now. If someone sews a button on a shirt, they say, ‘I’m in fashion.’ I say, ‘No, you’re not in fashion, you’re in the apparel business, which is a wonderful business—a better business, really—one that will more than likely help you survive.’ And that’s what Willi was doing.”

Smith’s sketches for Deep South Suite, choreographed by Dianne McIntyre, 1976.Courtesy of Silvia Waters and Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc.

Smith’s first major role, in 1969, was as head designer of an upstart sportswear label called Digits, where he quickly made a name for himself with bright, bold prints; flowy high-waisted pants; and an ahead of its time marketing campaign featuring women kicking it on the gritty streets of New York. Two years later, he became the youngest designer to be nominated for a Coty Award, then the fashion equivalent of an Oscar. (He finally won in 1983, on his fifth nomination.) Digits was also where Smith first encountered Mallet. A Parisian on vacation in New York, she was shopping some samples of French fabric around the Garment District in an attempt to bolster her travel funds. The two hit it off, and when Mallet moved to the U.S. a few years later, Smith hired her as his assistant. “He said, ‘We go shopping, look at the stores and see what they have, then we have lunch with the editors,’ ” Mallet remembers. “That sounded pretty good to me!”

Smith in his New York office, designed by the architecture and environmental arts studio SITE, 1982.Courtesy of Site/James Wines, LLC.

Too good to last, in fact. By 1974, the economy was in free fall and Digits was on the brink of bankruptcy. Smith resigned and attempted to establish his own label with his beloved sister, Toukie, a model now perhaps best known as a longtime paramour of Robert De Niro’s. But a Seventh Avenue firm got involved, buying Smith’s name and denying him creative control, and the venture ended in a lawsuit. Meanwhile, -Mallet had found some success manufacturing hippie-chic tunics in India. “Willi was so depressed that I said, ‘Why don’t you come to India with me? You can design a collection and then I will try to sell it,’ ” -Mallet says. The two came back with a small line inspired in part by Indian police uniforms. One pair of trousers in particular created a sensation. “It was based on a cargo pant, but it had an adjustable wraparound waistband,” Mallet says. “We had only one size, but anyone could wear it. It started selling like crazy, and everybody wanted to know: Who is making these pants?” Mallet and Smith set up their business, WilliWear Ltd., in 1976.

A look from WilliWear’s fall 1983 Street Couture collection.Photography by Max Vadukul, Bill Bonnell papers, Vignelli Center for Design Studies, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY.

As a designer, Smith was an utter anomaly at the time. Black, gay, and magnetically charming, he was widely known and well connected (Smith designed Edwin -Schlossberg’s suit, for example, when he married Caroline Kennedy) yet completely committed to making affordable, accessible clothing on a mass scale. “I don’t believe my creativity is threatened by commercialism,” he told Fashion World in 1978. “Quite the opposite—I think that the more commercial I become, the more creative I can be, because I am reaching more people.” He staged his fashion shows at such culturally vaunted locales as Holly Solomon Gallery and the Alvin Ailey theater, with Ailey’s dancers as models, and at the same time was cutting his designs into patterns for Butterick and McCall’s so that women like his grandmother could whip them up at home. For Smith, even as the scrappy 1970s turned into the luxe-obsessed ’80s, being aspirational was never particularly interesting. As Wines puts it, “He was trying to be a real polar opposite of Ralph Lauren.”

Théâtre National Daniel Sorano dancers on the set of Expedition, 1985.Photographed by Max Vadukul, Bill Bonnell papers, Vignelli Center for Design Studies, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY.

The accessibility of WilliWear was about more than just price point. Simple, adaptable, and forgiving, Smith’s designs suited a wide variety of body types and aesthetics. “When you look at things that came later, like Issey Miyake’s Plantation line, Smith was already doing that sort of stuff in the ’70s, the loose silhouettes and cotton garments,” says Kim Jenkins, a fashion historian who debuted the first course on “Fashion and Race” at Parsons in 2016. “It was absolutely novel at that time.” It was also wildly successful. With WilliWear, which was sold in more than 500 stores in the U.S. and internationally, Smith—-according to Elizabeth Way, assistant curator at the Museum at FIT—“had one of the biggest firms in New York. He was manufacturing on a really large scale, and the trajectory of his company was such that it was growing exponentially. It’s entirely possible that he could have had a brand as big as some of the really big American household names that we have now. But of course we will never know.”

Portrait of Willi Smith, c. 1981Courtesy of and Photographed by Kim Steele.

According to Mallet, from their very first trip to what was then known as Bombay—even though his luggage was lost, forcing him to walk around for days in short shorts paired with cowboy boots—Smith was enamored with India. It seems particularly cruel that it was during a visit there that Smith developed the bacterial infection and pneumonia that would end his life. He died, upon returning home to New York, at Mount Sinai -Hospital in April 1987. Tests later revealed that—-unbeknownst to even his closest friends—he had AIDS. Whether he was unaware of his status or simply in deep denial remains a mystery.

After Smith’s death, Mallet made an attempt to keep the business going, bringing the hypertalented designer Andre Walker on board and even opening new boutiques. But the label ultimately folded, in 1990, and the fashion world, obsessed—almost by definition—with what’s next, moved on. As Way puts it, “New York has a really short memory for its designers.” It probably didn’t help that Smith died of AIDS at a time when the mere mention of the disease was enough to induce panic. And of course, as Jenkins points out, “Fashion history, for the most part, has been white history. On the whole, we have designers of color missing from the textbooks.”

Willi Smith Fall 1985 CollectionCourtesy of Fashion Institute of Technology, SUNY, FIT Library Special Collections and College Archive, and Peter L. Gould/Images.

In fact, when Cunningham Cameron came across photos of Smith’s showroom cum environmental art installation while exploring the SITE archive last year, she was completely unfamiliar with his work. Wines quickly corrected that situation. “James—who is 87 and sharp as a tack—was like, ‘Let me school you on this amazing man,’ ” she recalls. “He talked about the downtown New York art scene, and how Willi had gone on to produce one of the most successful mainstream brands. And also about how, after he died of AIDS, he never received the recognition that he deserved.” Cunningham Cameron became determined to tell Smith’s story.

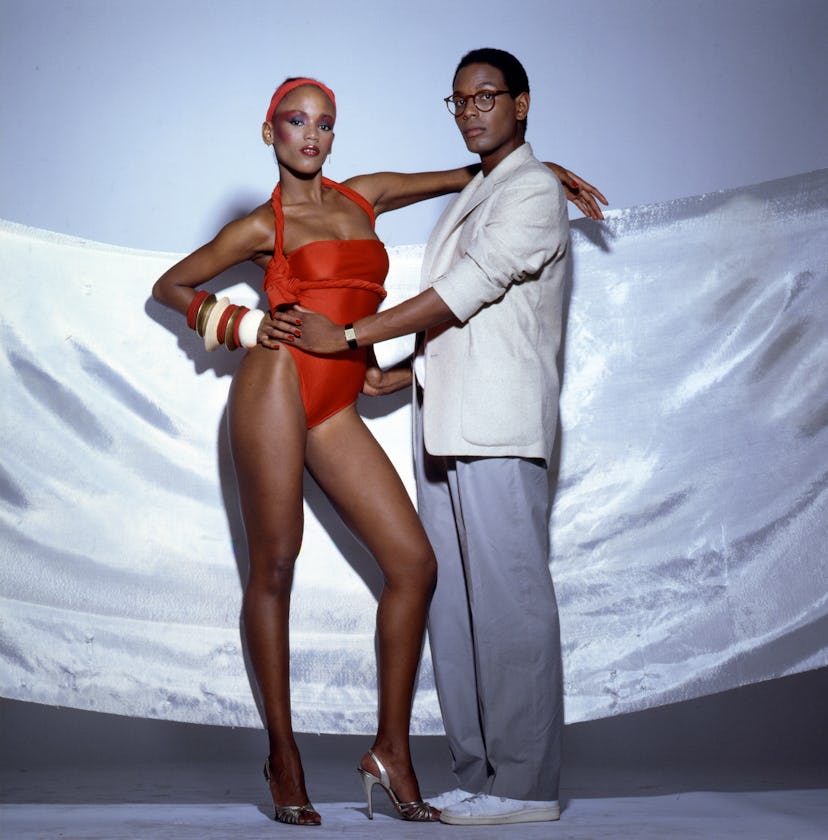

William Baldwin (left) and another model in looks from WilliWear’s spring 1986 presentation. Courtesy of Fashion Institute of Technology SUNY, FIT Library Special Collections and College Archive & Peter L. Gould/Images.

The resulting exhibition, “Willi Smith: Street Couture,” opens March 13 and runs through October 25. (The accompanying book was edited by Cunningham Cameron and published by Rizzoli.) Like Smith’s work—and, in many ways, his life—the show is a collage of seemingly disparate elements that coalesce into something that makes perfect sense. Because the clothes were in such short supply—Cunningham Cameron was ultimately able to get her hands on some key pieces, but they make up only about 20 percent of what’s on display—the exhibition includes loads of graphic materials; some 15 videos; two scripted films; oral histories from friends and collaborators; and a re-creation of Smith’s PS1 show. Wines, as the exhibition designer, aims to capture the feeling of Smith’s iconic showroom. “It’s going to be interesting,” he says, “to take all this gray iron and stick it in Carnegie Mansion.” For Wines, the point is to give museumgoers who might remember Smith’s name only from the department store racks a sense of his virtuosic creativity. Hardison, meanwhile, has a simpler wish. “I don’t want to call him an artist, or even a streetwear designer,” she says. “That puts him in a box. Willi was a star. I just want people to know that he existed.”