Vito Acconci Doesn’t Want to Be the Godfather of Transgression Anymore

Why won’t anyone, including Shia LaBeouf, let the artist live down the ’70s? An afternoon with the former provocateur in winter.

It’s often said that nowhere else is the provocateur more richly rewarded than in the art world, but even there provocation is a game for the young. Maurizio Cattelan, who enraged the Milanese with lifelike sculptures of three adolescent boys hanging by rope in a city square, retired early (even if he is now making his return). Chris Burden, who allowed himself to be shot by a gun in a gallery, moved onto installations of cars and currency. Even Jeff Koons had an early spell of exhibitionism in the ’90s with his short-lived first wife, the porn star Ilona Staller, before returning to crowd-pleasing monuments to artifice.

At 76, Vito Acconci, once dubbed the Godfather of Transgression, is a provocateur in winter. When I visited his studio in Brooklyn’s Dumbo recently, he greeted me dressed in a black button-up, black trousers, and dark sneakers. Never a tall man, he carried a slight hunch and moved slowly, but there remained a suggestion of the cool, slim-hipped wiriness that made him such a captivating performance artist in the ’70s.

“Do you want some wine?” he asked. I recognized the gravel in his voice from his videos, such as 1973’s “Undertone,” when he sat at a table and tried to persuade both himself and the viewer that there was a woman hidden beneath, rubbing his thighs.

He poured one for me. “I don’t drink as much as other people do,” he said. I was trying to place the context for this comment when his wife Maria Acconci, more than 40 years his junior, appeared. It was apparent that the glass in her hand was not her first.

“How is the installation going?” I asked. “Where We Are Now (Who Are We Anyway?),” a survey of Vito’s early work through 1976—unquestionably, his most famous (and infamous) years—is opening at MoMA PS1 on June 19.

“I think a lot of things are worked out,” Vito said, diplomatically.

“That’s not true,” Maria, who works with him in the studio, interjected. She and Vito met after he gave a commencement speech at Pratt Institute, which she attended. “It’s not going great. But it’s going to get done.” She took a sip, and her voice seemed to jump half an octave. “I’ve been together with Vito for 12 years, and I’ve seen a lot of bad shows happen that I’ve not had a say in. But I will not allow that to happen at PS1.”

“Some were bad,” Vito admitted.

“No, not some. All!”

“You think all of them were bad?” Vito said, incredulous.

The exhibition at PS1 was dreamed up by Klaus Biesenbach to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the museum’s founding in Queens in 1976, and therefore restricted to work up until the birth year, but it is hardly uncommon for Vito, who has been working as an architect and designer since the late 70’s (he officially established Acconci Studio in 1988), to find that the later parts of his career—the post-transgression years, to put it reductively—have gone under-appreciated by both the public and the art world.

To this day, Vito’s most famous piece is still 1972’s “Seedbed,” in which he lay under a wooden ramp in Ileanna Sonnabend’s New York gallery, masturbating while staring up through the floorboards. Speakers broadcasted his autoerotic fantasies about each gallery visitor as they passed overhead. Like Burden’s bullet to the arm, it’s the kind of piece that, once a young person gets hold of its legend, can cause him to mistake its direct confrontation of fantasy and desire, not to mention Vito’s early theoretical inquiries into the nature of architecture (what does it mean to become part of the gallery?), for an excuse to let the id run wild and unchecked. (Shia LaBeouf has cited Vito as an influence.)

“You should feel bad that they’ve locked you in the 70’s,” Maria said to Vito, in the tone of a challenge. By now, the three of us were seated around a large table. I focused my attention on the spread of chips and guacamole in front of me.

“But this started a long time ago,” Vito protested.

“And you feel bad about it! Say something about how people keep you in a prison from 1968 to 1976!”

Vito’s pained look turned to resignation. He did not want to say it, but he’d already said as much two years ago, when he told a Sydney newspaper, “It’s frustrating—I haven’t done that kind of stuff for years and years. But I don’t know how to disown my background.” And when Richard Prince interviewed him for Bomb in 1991, Vito admitted, “I’m afraid people pay attention to my stuff only when it has something to do with sex: that’s my art role, and I’d better live up to it.”

It’s ironic that “Seedbed,” and works like it, have come to represent Vito’s career. He’d never set out to be an artist in the first place. Born in 1940 to Italian parents in the Bronx, he studied under Jesuits through college—”I admit I liked the rigor,” he said—before eventually finding his way to the MFA writing program at Iowa, which was famous even then. (Philip Roth was teaching there at the time.) He never seriously considered making art until he arrived in New York, and even then it was a reaction—as most groundbreaking work tends to be—of dissatisfaction with what he was seeing.

“I didn’t like art,” he recalled. “I wanted stuff to be alive.”

Vito made his first artwork in 1969, and what he considers his first mature work at the end of 1970. He showed me instructions he’d written down for “Ballroom,” a 1973 performance piece, which is how the majority of his output as an artist is documented—as directions on paper, stored in 11 rows of five-stacks of file cabinets in his studio. Among them, surely, are some of his most well-known performances, such as the time he burned all the hair off his chest (“Conversions 1,” 1970-71), or the time he bit various parts of his naked body so hard his teeth broke the skin (“Trademarks,” 1970).

In terms of impact, Vito’s work as a video and performance artist is not far from that of Burden and Bruce Nauman as among the most influential of his era. But Vito has always been a restless autodidact. In the span of about a decade, he evolved himself from a fiction writer to a poet to a performance and video artist to an architect and designer. “Even now, I’m teaching architecture at Pratt, and I’ve never taken an architecture course,” he said.

It’s understandable that Vito, and by proxy Maria, who seemed as loyal as she was difficult, would be frustrated that this current phase of his career, during which he’s seen over 20 of his projects realized, falls deep in the shadow of work he no longer wishes to activate. The day after our meeting, Vito wrote me from his and Maria’s joint email account: “I hope Maria & I—even when we argue—show how close & closer we can be (even when 1 of us seems to berate the other, the berating gets us inside each other, mixed together.”

When Maria stepped away for a moment, I asked Vito if he was indeed okay with constantly having to relive the 70’s.

“No!” he cried. “Did I die? I would pinch myself, but it might be too late.”

Photos: Vito Acconci Doesn’t Want to Be the Godfather of Transgression Anymore

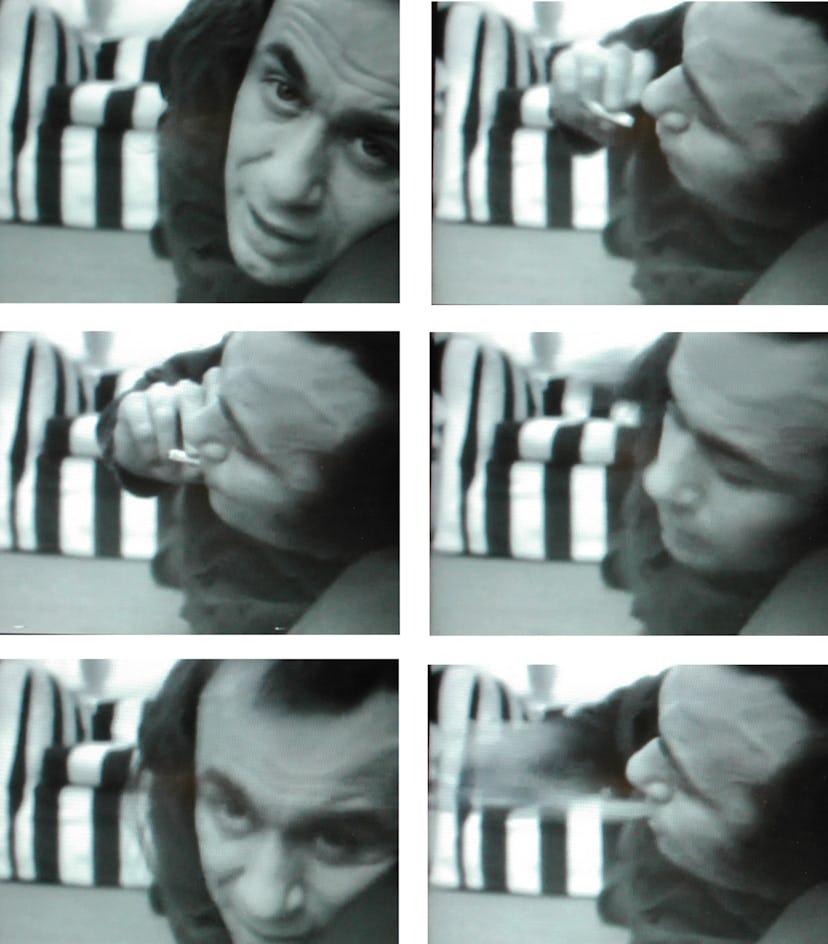

“Theme Song,” 1973. Courtesy of Acconci Studios.

“Theme Song,” 1973. Courtesy of Acconci Studios.

“Three Relationship Studies,” 1970. Courtesy of Acconci Studios.

“The Red Tapes, 1977.” Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

“Where We Are Now (Who Are We Anyway?,” 1976. Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery, New York.