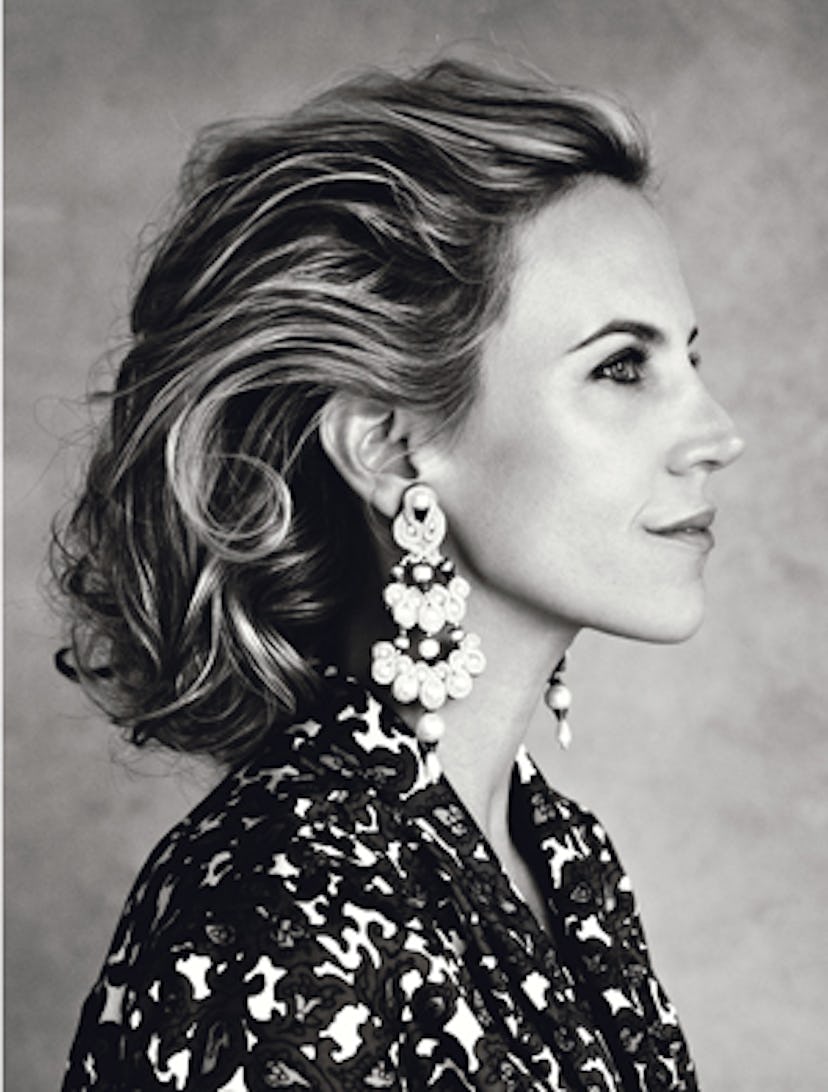

Tory Burch

After Oprah Winfrey lauded her as the next big thing, society’s golden girl grew her label into a global empire. but, as Kevin West reports, little miss perfect refuses to gloat.

At some point between the opening of Balthazar and the closing of Moomba—events that bookended the Puff Daddy–and–dot-com froth of fin de siècle New York—I found myself between parties with an old social pro. “One day,” he said, “you’ll look back and say, ‘I was in New York during the boom-boom nineties.’ ”

Right he was. From 1996 to 2000, I was reporting for W’s Eye desk and Women’s Wear Daily, covering New York’s young flash-and-cash heiresses: Crown Princess Marie-Chantal of Greece (the decade’s best money-meets-title match), Lulu de Kwiatkowski (who once dressed for a costume party as 99 pounds of cocaine, because that’s how much she weighed), Rena Sindi (who reinvented the at-home theme party), and Marjorie Gubelmann (who, after one gala at the New York City Ballet, joined the boys for a gay bar crawl through Alphabet City dressed in her ball gown and emeralds).

Tory Burch led a somewhat more reserved social squad—Southampton types to the others’ Saint-Tropez—that included Gigi Mortimer, Marina Rust, Jennifer Creel, Aerin and Jane Lauder, and Serena and Samantha Boardman. At that point, Burch was simply a nice girl from a nice part of Philadelphia who had worked in fashion public relations before marrying the banker Chris Burch. To be honest, she was somewhat overshadowed by the glitzier young women who were born higher up the socioeconomic food chain; looking back, Burch describes herself as a “bystander” to the era. “I grew up in Pennsylvania, so New York was very different for me,” recalls the 46-year-old designer. “It seemed like a new generation of artists and designers was emerging. I was young, and it was fun.”

Both sets of Team Nineties loved to be in the press, even as they professed to hate the word “socialite.” Instead, these girls declared, they wanted to work. The Lauders took actual jobs in the family company, and others in their peer group started businesses, since well-funded entrepreneurialism offered the status of work without the rigid 9-to-5 grind. De Kwiatkowski went into fabrics; Marie-Chantal created a children’s clothing line; and Gubelmann distilled the essence of high-end merchandising into the name of her candle company, Vie Luxe. Perhaps the society entrepreneurs also wanted to capitalize on the decade’s fast-company-startup ethos. Money was loose in the age of Gucci, logos, and bling, and the papers were filled with news of Bernard Arnault and François Pinault spending furiously to build their respective luxury-goods empires. At the height of the frenzy, in December 2000, LVMH acquired Donna Karan in a deal valued at $645 million. What ambitious young socialite, already steeped in the lingo and lifestyle of luxury, wouldn’t have wanted to have her brand similarly snapped up?

To my surprise, the nineties alumna who vaulted past her classmates was a late entrant into the race, but in the eight years since Burch opened her first boutique on Elizabeth Street, she alone has distanced herself indisputably from claims of dilettantism and has outlasted the skepticism that pegged her company as a rich lady’s hobby or, at best, a flash in the pan. Tory Burch will do $800 million in sales this year at 83 boutiques worldwide, some of which the founder hasn’t yet had time to visit. Burch’s business model seems to be the millennial summing-up of multiple Seventh Avenue legends from previous decades: the colorful preppy fun of Lilly Pulitzer, the throw-it-on ease of Diane von Furstenberg, the intuitive grasp of fashion-as-sexual-politics of Donna Karan, and the faultless lifestyle marketing of Ralph Lauren—all hybridized with the price-point savvy of J. Crew.

When Burch launched her label, my first thought was, Why would she bother? She appeared to have it all: Waspy good looks, picture-perfect children, a rich husband, and a sprawling Pierre hotel apartment that was famous for being the best of her generation’s, a rarefied distinction that ranked her with older salonistes, from Mrs. Astor to Nan Kempner to Susan Gutfreund. In the years since, I’ve often felt hard-pressed to define what makes her tick. In conversation, where you would expect to feel the heat of her ambition, you instead get pleasant reserve—steady nerves in the face of a vertigo-inducing rise have been Burch’s hallmark. Her composure has remained unruffled by her divorce from Christopher Burch, and by her subsequent relationships with high-profile boyfriends—first Lance Armstrong, and currently Warner Music chieftain Lyor Cohen. The family center has held. “My boys are doing great,” she says of her three sons. “That’s all that matters to me.”

Our conversation yields one tiny clue, however. When I ask what she wanted to be when she grew up, Burch replies: “I think it was probably around social work or being a psychiatrist.” When I ask what her parents wanted her to be, she pauses, caught for once without an answer polished smooth by eight years of constant media exposure. “I would say, um, early on, a tennis player,” Burch speculates, allowing a glimpse into a childhood in which you played by the rules, but you played to win. That Burch still comports herself with the mannerly intensity of a country club tennis champion speaks to the precise quality of her early home training.

“I love to work,” Burch said during her 2005 appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show that anointed her “the next big thing” and generated 8 million hits on her company’s website. “I live a life where I take chances, and if I believe in something, I go for it.”

With next year’s release of her fragrance from Estée Lauder and continued expansion into emerging markets, her company will almost certainly top the billion-dollar milestone before its 10th anniversary. In other words, when I wondered years ago why Burch would bother opening a store, I was asking the wrong question. She was launching a lifestyle empire, and she knew it at the time. “I had more guts than I probably should have had,” she says.

Burch’s success since then, her mission accomplished to win big while still playing nice, singles her out as the boomiest social figure to have emerged from the boom-boom nineties.

Hair by Jimmy Paul for Bumble and Bumble; makeup by Maki Ryoke at Tim Howard Management.