The Times of Bill Cunningham Shows a Different Side of the Godfather of Street-style Photographers

It wasn’t until two, maybe three hours into the interview that director Mark Bozek asked Bill Cunningham, the godfather of contemporary street style and one of fashion’s kindest, most exuberant personalities, “Are there things that make you sad?” He’d already asked about the extremes of the late photographer’s work—the parts that he considered the most fun, the most exciting, the hardest, the easiest. So why not the saddest?

At that moment, which eventually became the emotional climax of Bozek’s new documentary, The Times of Bill Cunningham, Cunningham seems to crumble. “AIDS has been so, tearing apart…” he starts, eyes suddenly shining. It’s as if the joy he sought in his work, and the wonder with which he viewed the world, was an antidote to the grief that lurked immediately beneath the surface.

“It was time for me to just be quiet,” Bozek said recently. “He clearly had a lot to say—a lot more than I ever anticipated.” It was the unexpected result of what was supposed to be a brief interview. In 1994, the notably private Cunningham, whom the CFDA was planning to honor at its annual awards ceremony, approached Bozek about making a minute-long introductory video. Bozek, a television producer, had recently done a story on the photographer for a style program on Fox. They planned to talk for 10 minutes at the home of Cunningham’s closest friend, Suzette Cimino—and they ended up talking for more than two hours, until the videotape simply ran out.

Steven Meisel and Anna Sui (right) in a never before seen Bill Cunningham photo.

At the time, AIDS “was just throttling the industry,” Bozek said. New York designers like Perry Ellis and Willi Smith, for whom Bozek once worked, had already died due to complications from the disease. Cunningham had lost personal friends like the fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez to the disease; Lopez’s longtime collaborator Juan Ramos would follow soon after. “I think you go out, and you find something wonderful and something to inspire,” Cunningham says. “You pick up where a lot of these extraordinary talents that we’ve lost have left off, and you try to carry on for them.”

The Times of Bill Cunningham, out Friday, lays out Cunningham’s life and career chronologically, in his own words, filling in a few gaps with voice-over narration by Sarah Jessica Parker. And where the 2010 documentary Bill Cunningham New York offered a contemporaneous account of the photographer’s work and process—going inside the newsroom of The New York Times and into his studio apartment above Carnegie Hall—The Times of Bill Cunningham acts as more of a retrospective, making an argument for Cunningham not only as a savvy street-style photographer but as one of the late-20th century’s most insightful documentarians. Pedaling about town in his blue chore coat, he photographed New York’s gay pride parade every year since its start; he shot Diana Vreeland styling the Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute exhibitions; and he went to France to document the Battle of Versailles. He shot the reclusive Greta Garbo, famously, and Jackie Kennedy. (Cunningham wasn’t just an observer: He started out as a milliner under the name William J., even selling a few pieces to Elsa Schiaparelli, and he worked with Chez Ninon, where he dyed a Balenciaga dress black for Jackie Kennedy to wear to her husband’s funeral.)

The receipt Cunningham saved for changes to a dress Jacqueline Kennedy wore to her husband’s funeral.

Having shelved the interview in 1994, Bozek didn’t return to it till Cunningham’s death, at 87, in 2016. He decided to screen it for a group of Cunningham’s friends, including the late designer Isabel Toledo and her husband, the artist and fashion illustrator Ruben Toledo, to gauge their response. (The Toledos met Cunningham outside Xenon, the Times Square nightclub that was Studio 54’s only true rival, when they were teenagers. Isabel was wearing a white tulle dress of her own design, held up with fishing wire so “it was almost like she had stepped into a white cloud,” Ruben told me recently. “She looked like a beautiful little creature from outer space.”)

From left: Diana Ross, Diana Vreeland, Racquel Welch, and Diane Von Furstenberg at the 1981 Met Gala.

Cunningham kept his family, his work, and his social life so siloed that Ruben couldn’t believe the extent of the material Bozek had collected during that interview. He was convinced Bozek “had to make this available to as many people as possible,” he told me. (The designer Anna Sui echoed this separately: “There’s so much more about Bill in there that a lot of us didn’t know,” she said.) Cunningham’s work went well beyond simple trend forecasting: “It’s documenting clothing on people, documenting fashion, documenting the whole spectrum of the fashion world,” Ruben said, “from designers to the people who make it to the people who wear it and where they go and why they’re wearing it.” (Ruben painted the watercolor portraits of Cunningham that illustrate the film’s poster and opening credits.)

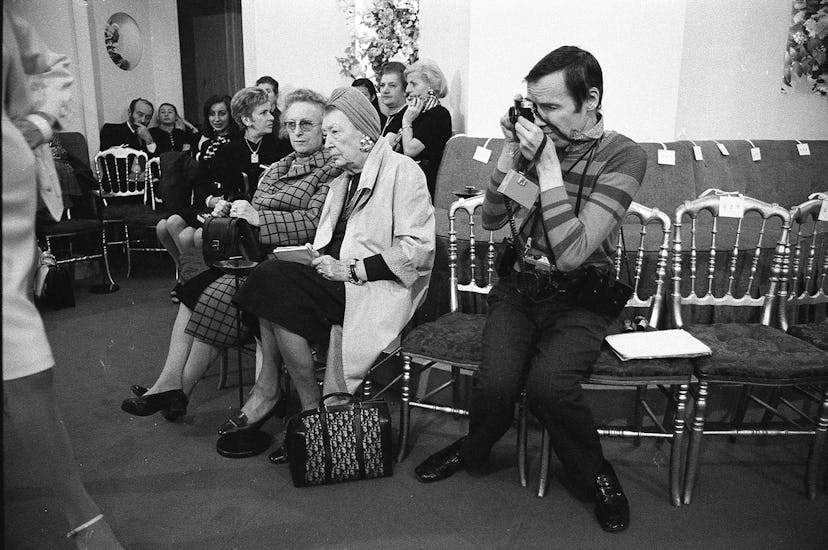

Ruben (center) and Isabel Toledo with Stephen Gan.

Still, Bozek was aware of the potential obstacles: “There’s no point in doing a redux of [a documentary] that came out and did well and was well responded to just because I had this footage,” he said. “There had to be an arc to it, and that arc was certainly the archive.” Over a couple of glasses of cheap wine in the lobby of a Holiday Inn in Orangeburg, New York, Bozek showed a rough cut of the documentary, pieced together on his home computer, to Cunningham’s niece Trish Simonson, who manages his estate. Immediately, she granted him access to Cunningham’s archive of 3 million images. (Of those, Bozek scanned what he estimated to be 25,000 photos; more than 500 ended up in the film, and a few more are featured exclusively here.)

Liza Minelli (left) and Pat Cleveland at the Battle of Versailles, in 1973.

Many of those images went unpublished in Cunningham’s lifetime—he never printed an image of the pride parade, out of consideration for the privacy of his subjects. (The Times of Bill Cunningham also alludes to a moment explored further in Bill Cunningham New York, in which the photographer departed Women’s Wear Daily over a particularly nasty headline.) “I do see photos that I don’t take—that I should take, but I don’t have the guts,” he says in the film.

Still, “there’s no question in my mind he knew they were going to be published at some point,” Bozek said, likening the image archive to Cunningham’s posthumous memoir, Fashion Climbing. (The memoir, Matthew Schneier wrote in The New York Times, in 2018, “amounts to a major archaeological revelation.”) The photographer “was meticulous” in his documentation, Bozek said, saving receipts and audio recordings as well as a vast trove of contact sheets and negatives.

And the inverse was also true: Cunningham took photos that no one else was taking, whether of Manhattan’s “Men in Skirts” or of talents only just emerging. “He was kind of fashion’s biggest cheerleader,” Sui said. One afternoon in Manhattan, a young Pat Cleveland “came spinning out” of Henri Bendel, she told me, wearing a plaid Stephen Burrows coat, a suede bag, brown patent “baby shoes” with candy-striped shoelaces and red tights. Cunningham was there to take her picture. “I wasn’t being photographed by everyone at that time; he just picked out the sort of odd ones in the corner,” Cleveland said. “It just so happens I was one of the odd ones.”

As much as Cunningham found motivation in the work of peers like Lopez and Ramos, his enduring influence underlines the same effect he had on those around him. “You just think, Oh my gosh, I was so lucky,” Cleveland said. “How lucky I was to have this person in my life.”