Suzie Zuzek Was a 1960s Icon Who Never Got Her Due

Suzie Zuzek drew some of Lilly Pulitzer’s most iconic patterns. Now, her place in American fashion history is being restored.

Take a deep breath and do your best to erase the current iteration of Lilly Pulitzer from your mind’s eye. Just from reading the name, you may have already conjured images of a sorority sister on the sidelines of a polo match, or a tie slung loosely around the sweaty neck of an heir to a sugar fortune. Maybe you just see a disembodied riot of technicolor.

Banish those visions and bear with me for a moment, because the Lilly Pulitzer that defined resort fashion in the 1960s and ’70s was an entirely different thing.

Decades before Pulitzer’s name was licensed for a new brand releasing prints with names like “Who Let the Fronds Out” rendered in colors as subtle as a variety pack of Sharpie highlighters, the company was a family affair, churning out shift dresses and unisex jeans known for their kooky, bohemian patterns that were outré and deeply traditional at once.

A man wears a Lilly Pulitzer jacket in Suzie Zuzek’s Hi-Lilly-Biscus print, circa 1968.

The simplified version of the company’s origin story is a well-worn one: Free-spirited Palm Beach heiress Lilly Pulitzer wanted something to wear while tending her husband’s orange juice bar that would hide juice splatters and not be oppressive in the Florida heat. So she and some friends sewed up a couple of dresses in brightly colored, patterned fabrics, and an empire was born.

The more interesting part was left out, until recently: Those prints that made the brand as instantly recognizable as Pucci’s abstract swirls or Burberry’s black and tan plaid were painted almost entirely by one woman in Key West, an artist named Suzie Zuzek who died in 2011. Her archive was presumed lost, thrown away when the original Lilly Pulitzer company filed for bankruptcy in 1984, until it was unearthed in the sub-flooring of a warehouse a few years ago.

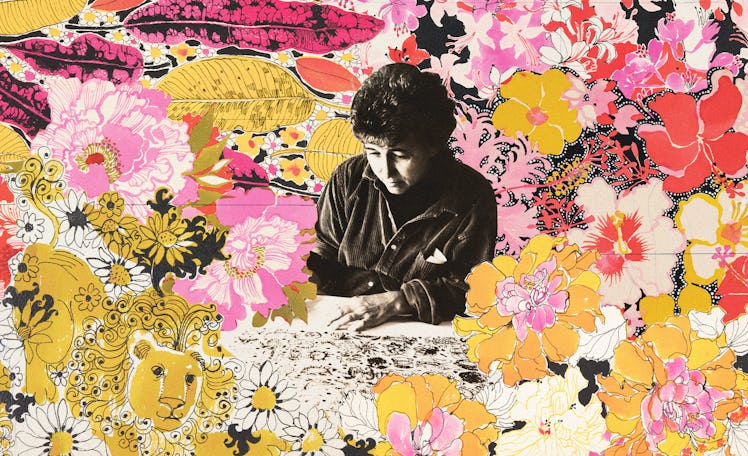

Suzie Zuzek at her desk in Key West Hand Print Fabrics, late 1960s.

Key West Hand Print Fabrics workroom in the 1960s.

Zuzek’s work, which went unattributed during her lifetime, is the subject of a Rizzoli book, Suzie Zuzek for Lilly Pulitzer: The Artist Behind an Iconic American Fashion Brand, and an exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, which finally re-opens to the public on June 10th after being closed for more than a year. Both projects aim to restore Zuzek’s place in fashion history, while also re-examining the impact of the original Lilly Pulitzer designs on the evolution of American style.

“Suzie Zuzek is somebody whose work is familiar to millions of people, and who had a major impact on the social history and the material culture of the 1960s and ’70s, but most people have never heard her name,” said Cooper Hewitt textile curator Susan Brown, who also contributed an essay to the book. “Textile designers are so rarely credited for their contributions to fashion,” she added. “I think it’s a story that will be really relatable to a lot of creative people who work anonymously.”

Before Lilly came to embody a look that the critic Cintra Wilson once described, in a New York Times story about the brand’s Madison Avenue store in 2010, as a “mescaline rapture of a tropical morning on an infinite golf course,” Zuzek’s designs gave simple shift dresses and mini skirts a varied sense of sophistication. Printed on flat-cut garments with few embellishments, they were the entire look. “She could be inspired by anything,” Brown said. “From Roman coins to cabbages to African wildlife.”

Zuzek’s graphics are like narrative paisleys. Her animals have a sly, kinetic warmth: Tigers peek out from behind palm fronds, doves dissolve into abstract swirls the color of the ocean. Some of the more saturated prints wouldn’t look out of place on a Prada spring runway.

Allen, 1978; San Marco Mosaic, 1970; Pop-Your-Lilly, 1968; and Lilly-Birds, 1967. All drawings by Suzie Zuzek.

Suzie Zuzek, Suzie’s Suns, 1965.

Suzie Zuzek, Zek’s Zoo, 1974; brush and watercolor, pen and ink, graphite on paper.

The road from basement obscurity to posthumous recognition was a long and winding one, spearheaded by a St. Louis lawyer named Becky Smith, who first encountered Zuzek’s designs while on the hunt for vintage upholstery fabric. She ended up in Key West and ran into Zuzek’s daughter, Martha, who shared her late mother’s story. Smith says she was captivated, and immediately made it her mission to bring the story to light: “What if your mom sat on the second floor of an art studio for a quarter of a century and created an iconic look through her creative genius and nobody knows her name?”

Born in 1920, Zuzek grew up on a dairy farm outside of Buffalo, New York. After serving in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps during World War II, she studied textile design and illustration at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. She graduated at the top of her class and worked for the New York-based fabric company Herman Blanc before relocating to Key West with her husband, from whom she separated not long afterwards. Eventually, she ended up with a job at Key West Hand Print Fabrics, a local outfit run by a group of former Broadway set designers.

“There are a lot of larger-than-life characters in the story, around her, but she herself was pretty quiet,” Brown said, recalling conversations she had with local residents for a short documentary that will accompany the exhibition. “I get the feeling she was more taciturn than shy. People say she had a really wicked sense of humor.”

Zuzek and Pulitzer first crossed paths in 1962, when Pulitzer flew down to Key West, marched barefoot into the print shop, and, according to one source interviewed by Brown, dumped a Gristedes bag full of fabric on the counter and asked “Is this your shit?” Pulitzer ordered three hundred yards on the spot. Upon returning to Palm Beach, she called to increase her order to three thousand. Four years later, she was going through more than five thousand yards every week, with most of the designs custom-made by Zuzek.

Over the years, Zuzek’s designs could be seen on the Key West flag (a version of which is still used today), a tile mural at the local library, splashed across sailboats and head-to-toe on Florida tourism board uniforms. They also ended up on Jackie Kennedy, who was photographed in Zuzek prints in Hyannis and Ravello.

The sailboat Elysium sported two Suzie Zuzek designs: Sun Sail and Sail Birds, on its spinnaker in the 1970s.

Jacqueline Kennedy wore a Lilly Pulitzer shift in an early Zuzek floral to greet husband President John F. Kennedy on Squaw Island at Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, July 20, 1962.

Caroline Rennolds Milbank, a fashion historian who also contributed a text to the book, noted that photographs like these, of a first lady wearing casual, knee-baring garments that didn’t require traditional underpinnings like girdles or stockings, helped propel fashion forward. Pulitzer’s jeans, which were worn by men and women, also predated widespread unisex fashion and the first “designer” jeans by more than a decade. “There’s probably a snobbery that it’s such cheerful work that it can’t be serious,” Millbank mused. “But it was radical and traditional at the same time.”

As Brown noted in her essay, Zuzek was one of the most collected American textile artists of the second half of the twentieth century. But the dissolution of the Lilly Pulitzer company in the ’80s separated the archive from Pulitzer’s trademarked name. When the brand was reconstituted in the ’90s by an investor group, none of the original designs were carried forward. The Lilly Pulitzer name is now owned by a holding company that also controls Tommy Bahama.

For Smith, the erasure of all of Zuzek’s work was shocking: “No designer has split their trademark name with their entire design heritage,” she said. Together with a group of investors, she bought the archive, which contains more than 2,500 original drawings, and moved it to an art storage facility where it has been properly catalogued and conserved. The Cooper Hewitt exhibition slated for summer will feature more than 35 original watercolors and gouaches, as well as textiles and vintage Lilly Pulitzer pieces; the museum has also acquired 10 drawings for the permanent collection.

As far as the future goes, Smith hinted at potential collaborations with designers in the US and Europe, as a way to share Zuzek’s work with the world again, as well as limited releases of fabric by the yard. “We screened up a couple of the designs on a fabulous Belgian linen,” she said, getting excited about the possibilities. But the project is bigger than that: “We just want the world to know who Suzie Zuzek is, because she deserves it.”

This article was originally published on