Sarah Sophie Flicker Reflects on the Year Following the Women’s March on Washington

“If a truly intersectional feminist movement were an easy thing to accomplish, it would have been done a long time ago.”

Just four, maybe five days after the Women’s March on Washington last January, I received a call from an unknown number. (This has happened a lot this year.) And, when you’re a mom, you have to pick up—no matter how scared you are of the mystery on the end of the line. So I did. On the other end was Cindi Leive, then the editor-in-chief of Glamour. I had met her once, but didn’t know her well. Nevertheless, she immediately launched into why the Women’s March organizers had to write a book.

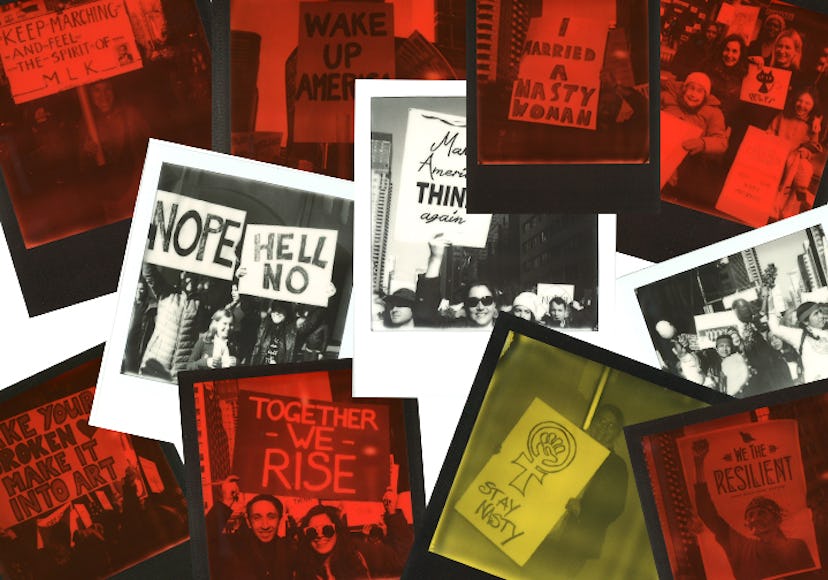

That was a year ago. Some of us were skeptical; while we had realized we would not simply be going back to our previous jobs and previous lives on January 22, and that none of us were walking away from the Women’s March, we knew nothing about how to get a book published. And there were other things to focus on. We were already becoming rapid responders to this administration’s immediately brutal policy proposals and beginning to plan “A Day Without A Woman.” But Cindi was insistent—it was almost like we didn’t have a choice—and now, a year later, Together We Rise, this amazing historical document, collection of essays, and blueprint for intersectional organizing, has come into the world. Books often take a year and a half to two years to release; in true Women’s March fashion, Paola Mendoza, Cassady Fendlay, the Women’s March national team, and I, with Cindi’s guidance, compiled this one in nine weeks.

It struck me as we were meeting with publishers and shepherding the book through production how crucial it is for women to tell their own stories, especially when it comes to historical events like the march. My daughter frequently comes home from her very progressive school—with textbooks filled with the tales of white men. So when it came to the march, we recruited (but really begged and prayed she would say yes) Jamia Wilson, who had recently been named the executive director and publisher of the Feminist Press at the City University of New York, to record an oral history and tell our story, warts and all. And, in addition to everything else, she also managed to write the most beautiful forward to the book. It never fails to make me cry.

I’ve said it before: If a truly intersectional feminist movement were an easy thing to accomplish, it would have been done a long time ago. We knew we had to include moments that were less flattering, many of which are still painful to talk about. But at the same time, it was so healing for us to get into it all. This is as much the real work that needs to be done as are marches, rallies, and protests: the critical daring discussions; the realization that, as long as we recognize our shared humanity and fundamental rights, it’s okay to disagree on the smaller things.

In the book, we revisit the challenges of ensuring diverse perspectives were included in the march’s decentralized leadership, and of ensuring the movements that came before, like the March on Washington, the Million Women’s March, and Black Lives Matter, were not erased in the course of planning our own demonstration. There was the inherent sexism we confronted, like when we were asked, over and over, if we had secured the necessary permits for the march. And there are moments that seem relatively minor in hindsight—like the tension between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton surrogates and supporters inside the Women’s March and the progressive movement more broadly. Nevertheless, we worked together, and we did so just a week after the election. Bob Bland has been so transparent about her own journey from being someone who wasn’t an activist to someone who was a major activist over a very short period. This involved, in part, a crash course in privilege and intersectionality and whiteness. Linda Sarsour, Tamika Mallory, Carmen Perez, Nantasha Williams, Brea Baker, Tony Choi, Janaye Ingram and Tabitha St. Bernard-Jacobs (and all the women and men of color involved with the Women’s March) have had the patience to work this out with us, despite some rightful distrust in white women. After all, 53 percent of white American women voted for Donald Trump.

“In the days after the election,” Carmen says in the book, “I didn’t know how to engage in conversation with white women, because we had heard that so many white women had voted for Trump.” We have all had to learn how to talk to each other, which has, of course, presented challenges, but these discussions have also produced some of our most rewarding shared moments.

We’re doing the work. We midwifed a movement. None of us feel responsible for this incredible year of activism we’ve seen, but I do feel like we helped set the tone, and we did so with intent. The Unity Principles, for example, which are laid out in the book (including the elimination, and subsequent reincorporation, of a term standing in solidarity with sex workers, another moment of controversy we contend with in the book), were very intentional. The movements we’ve seen succeed the Women’s March this year, like Me Too and Time’s Up, are examples of thoughtful, intersectional organizing. And the Women’s March itself is indebted to those who came before, like Black Lives Matter, without which none of this would have been possible. That’s what a real, vital, successful movement looks like.

In creating this book, there were absolutely voices that were left out, stories that remain to be told, like those of the state, global, and volunteer organizers. We recruited 28 national organizers to narrate an oral history of the march, assembled a toolkit for organizing, drafted a powerful afterword, sought out personal accounts of the march, and recruited 20 essayists to contribute their perspectives. I thought there was no way Ilana Glazer or Roxane Gay would participate—I was wrong. (Folks like Rebecca Solnit and Angela Davis were, unfortunately, out of town. This was, after all, in the middle of August.) These contributors had just a couple weeks to submit their essays, which no writer wants to hear. Yet, with the frantic, rushed pace, they had no choice but to be super raw and honest. Actors Yara Shahidi, Rowan Blanchard, and America Ferrera, Rep. Maxine Waters, and Transparent creator Jill Soloway all contributed. Whenever I’m on the brink of hopelessness, National Domestic Workers Alliance director Ai-jen Poo’s piece and civil rights activist Valarie Kaur’s “Revolutionary Love Is the Call of Our Time” essay both lift me up immediately.

Mass mobilizations remind us that we’re not alone, even if there are just 30 of you marching in a rural, conservative area. The day of the Women’s March helped us realize we outnumber them. Revisiting it now sets the tone for the upcoming midterm elections—which is why the “Power to the Polls” effort coincides so beautifully with this release. We are rolling out voter registration and “Get Out the Vote” campaigns in Nevada, working closely with organizers in swing states. It will only take flipping Nevada and Arizona, and holding onto the seats we already have, to have a Democratic majority in the Senate. In the days of mourning following the election, none of us could have imagined that, by January, we’d be gathering in joy and celebration. That spirit has to sustain us throughout the Trump administration. The issues his election has loudly brought to the surface are not new; Donald Trump does not represent anything that many haven’t represented before him. Out of despair, we can find hope—but it takes all of us showing up.

We end the book with these words: “We must continue to show up intentionally and with strategy, and to do so even for those who we do not know, with the commitment to the fundamental truth that my liberation is bound in yours, and yours in mine.” I etch this into my heart—and with a firm resolve and commitment to love harder and keep showing up as November approaches, I believe that we will win.

Meet the Women Who Are Making the Women’s March on Washington Happen

The executive director of the Arab American Association of New York, Linda Sarsour — a Brooklyn native, mother of three, and now one of the national co-chairs of the Women’s March on Washington — has been working at the crossroads of civil rights, religious freedom, and racial justice for 15 years. Once an aspiring English teacher, she joined the Arab American Association in its infancy, succeeding founder Basemah Atweh, her mentor, as executive director with Atweh’s death in 2005. “I grew out of the shadow of 9/11,” Sarsour said. “What I’ve seen out of bad always comes good, is that solidarity and unity, particularly amongst communities of color who feel like they’re all impacted by the same system.”

Tamika D. Mallory’s roots in community organizing and activism extend back to her early childhood: her parents were two of the earliest members of the Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network nearly 30 years ago, an organization for which Mallory went on to act as executive director. But it wasn’t until the death of her son’s father 15 years ago that Mallory found her niche in civil rights and flung herself headlong into activism. Now, she’s one of the four national co-chairs of the Women’s March on Washington, balancing organizing the march with her day job as a speaker and civil rights advocate. “We’re centering this march by having women to be at the helm of it, to organize it, and to be most of the speakers,” she said. “At the same time I think it’s very important that we never forget the fact that our men, our brothers, our young brothers particularly need this support.”

Fashion entrepreneur Bob Bland was nearing the due date of her second daughter, now seven weeks old, when she posted a Facebook event calling for a march on Washington during inauguration weekend. Nine weeks later, she’s one of four national co-chairs at the heart of the Women’s March on Washington — where she’ll march with her infant, her six-year-old daughter, and her 74-year-old mother. “We’re activating people who were previously content with sitting behind their computer and posting on Facebook,” she said.

For Carmen Perez, executive director of Harry Belafonte’s Gathering for Justice and one of the four national co-chairs of the Women’s March on Washington, work permeates everything else: “There’s no real life outside of activism,” she said. Just over two decades ago, Perez’s elder sister was killed — the anniversary of her burial coincides with the march, and with Perez’s birthday — and navigating the justice system motivated her to work with incarcerated young men and women, first as a probation officer and then with The Gathering, operating on the intersection of race, criminal justice, and immigration. “Oftentimes, when I’m in spaces, I am the only Latina and I have to speak a little louder for my community to be part of the conversation,” she said. “The work that I do around racial justice, it’s not just about Latino rights. It’s also about human rights.”

Californian ShiShi Rose, 27, moved to New York a year ago to develop her activism and writing. She previously worked at a local rape crisis center and assisted in educating therapists and counselors before turning her focus more squarely towards race, first via her Instagram account and then through public speaking engagements and writing. As part of the national committee for the Women’s March on Washington, Rose runs the group’s social media channels, from Instagram (where she has a substantial following) to Facebook. “Women encompass everything,” Rose said. “If you can fight for women’s rights, you can fight for rights across the board.”

A law student-turned-actress-turned-activist, Sarah Sophie Flicker was born in Copenhagen, the great-granddaughter of a Danish prime minister who has been credited with bringing democratic socialism to Denmark. She grew up in California before moving to New York to found the political cabaret Citizens Band, eventually joining the production company Art Not War. “Once you start breaking it all down, you realize the most vulnerable people in any community tend to be women,” she said. “All our issues intersect, and something that may affect me as a white woman will doubly affect a black woman or a Latina woman or an indigenous woman. So when we talk about a women’s movement, we need to be talking about all women.”

Vanessa Wruble, a member of the national organizing committee, is the uber-connector of the Women’s March on Washington. She’s also the founder and editor of OkayAfrica, a site connecting culture news from continental Africa with an international audience. It was Wruble who first messaged Bland on Facebook to connect her with the women who would eventually become her co-chairs: “She said, Hey, you know, you need to center women of color in the leadership of this so it can be truly inclusive,’” Bland recalled. Within a day, they were meeting for coffee; now, they’re marching together in one of the largest demonstrations in support of a vast array of causes in United States history.

Paola Mendoza, artistic director of the Women’s March on Washington, is a Colombian-American director and writer whose work has focused on immigrant experiences, particularly those of Latina women. “Women have never convened this way in our lifetime,” Mendoza said of the march, “and it’s being led for the first time ever by women of color.”

Janaye Ingram, who Michelle Obama once described as an “impressive leader,” is Head of Logistics for the March, in addition to being a consultant for issues like civil, voting, and women’s rights in Washington D.C.

Cassady Fendlay, communications director for the Women’s March on Washington, is a writer and communications strategist whose clients include The Gathering for Justice — the organization helmed by Women’s March national co-chair Carmen Perez. As the spokeswoman for the march, Fendlay is tasked with acting as its mouthpiece, ensuring its message is accurate, unified, and coherent.

In addition to being a producer of the march, Ginny Suss is the Vice President of Okayplayer.com and the President and co-founder of OkayAfrica — she does video production for both. Her background in the music industry runs deep, and she’s worked closely with The Roots for the past 13 years, serving as their Tour Manager for some time. She’s also produced large outdoor events like The Roots Picnic, Summerstage, Lincoln Center Out Of Doors, and Celebrate Brooklyn — vital experience for organizing a march of this size.

Last year, Nantasha Williams ran for the New York State Assembly as a representative of the 33rd district — which encompasses a region just east of Jamaica, Queens. Though she lost to Democrat Clyde Vanel, she’s putting her organizing skills to good use in the aftermath of the election, working on the logistics team for the march and assisting national co-chair Tamika Mallory.

When Alyssa Klein isn’t managing the various social media accounts for the Women’s March, she’s writer and Senior Editor at OkayAfrica, the largest online destination for New African music, culture, fashion, art, and politics. Based in both New York City and Johannesburg, Klein’s passion is movies and television, and has made it her profession to highlight creatives of color in both industries. Juggling social media is no easy side project, however. The Women’s March has approximately 80,000 followers on Instagram and Twitter, plus a over 200,000 on Facebook.

Shirley Marie Johnson is the March’s head administrator for Tennessee, as well as an author, poet, and singer. Primarily, though, she’s an activist and advocate for those who are victim to domestic violence, a cause that’s not only her focus at the March, but in her day-to-day life through her group Exodus, Inc., which aids those affected by rape, human trafficking, and other abuse.

Born in Shanghai, Ting Ting Cheng studied human rights at the University of Cape Town — and became an award-winning Fulbright scholar to South Africa — before heading to New York, where she’s now a criminal defense attorney at the Brooklyn Defender Services. All that’s no doubt come in handy for her role as Legal Director of the March.

Heidi Solomon is one of the three co-organizers for the Pennsylvania chapter of the Women’s March. Although she doesn’t have a long background in activism, Trump’s election moved her to take action, and she’s helped rally approximately 6,000 people from her home state.

Deborah Harris is a grassroots organizer and feminist self-help author who lives in Las Vegas, Nevada, and served as a community activist for 10 years in the fields of fashion, healthcare, at risk youth, and supportive women’s relations.

As Illinois’ state representative for the Women’s March, Mrinalini Chakraborty has taken the lead in coordinating the Chicago-area charge, organizing bus rides for well over a thousand women and other supporters. She’s also on the National Committee and is a coordinator for all 50 states coming to D.C.. And that’s in addition to her day job: She’s a graduate teaching and research assistant at the University of Illinois at Chicago for anthropology, not to mention a student and a dedicated food blogger.

After earning her Ph.D in psychology, Dr. Deborah Johnson is now studying social work at the University of Oklahoma in Tulsa — and making sure she stands up for both her and her daughter’s rights at the March, which she’s helping lead the way to for other Oklahomans.

Renee Singletary is an organizer, mother of two, wife of one, marketing consultant, and certified herbalist living and working in Charleston, South Carolina.

A yoga instructor, theater graduate, and local organizer, South Carolina native Evvie Harmon has brought her skills and energy to the march as its global co-coordinator alongside Breanne Butler. Together, they facilitate partner marches and local organizers around the world, bringing the whole thing into synergy.