Delayed Exposure

Sam Wagstaff was Robert Mapplethorpe’s lover—and, says a new book, the forgotten patron who changed photography.

On February 5, 1977, a floppy-haired boyfrom Queens named Robert Mapplethorpe truly arrived. Following the opening of the 30-year-old photographer’s New York exhibitions at Holly Solomon’s venerable SoHo gallery, where he showed refined studies of flowers, and at the Chelsea alternative art space the Kitchen, where he showed refined studies of S&M acts, 200 guests in black tie filled One Fifth, a stylish Art Deco restaurant off Washington Square. Diana Vreeland, Catherine Guinness, Elsa Peretti, and Halston; the art dealers Klaus Kertess and Charles Cowles; Danny Fields, the notorious manager of the Ramones and Iggy Pop; and Arnold Schwarzenegger all circulated amid a riot of downtown’s demimonde. Mapplethorpe turned up in a velvet dinner jacket—the feral photographer at his art world cotillion.

Presiding over this motley affair was Sam Wagstaff. Tall, charming, and beautiful in a richly disheveled fashion—he liked to wear a tuxedo with white sneakers and a studiously rumpled shirt—Wagstaff is remembered as the Diaghilev to Mapplethorpe’s Nijinsky, the older lover-patron who helped guide his protégé to renown. In the mid-1970s, when photography had yet to be taken seriously by the art establishment, Wagstaff, with his mix of élan, pedigree, and scholarship, became its ideal ambassador. “Sam Wagstaff was considered a great photography collector,” Holly Solomon observes in Patricia Morrisroe’s 1975 biography Mapplethorpe. “I wouldn’t have touched Robert without Sam.”

Wagstaff had many passions: cacti (as a child), art, photography, silver, boys. * The New Yorker writer Hilton Als described him as “an artist whose medium was collecting.” Wagstaff was known to use cocaine to heighten the act of looking. “There aren’t many people whose lives are that visceral with their art,” marvels Klaus Kertess in Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe, A Biography* (Norton). The author, Philip Gefter, makes a convincing case that Wagstaff played a pivotal role in photography’s acceptance into the art firmament.

“He knew an important movement when he saw one,” the patron Barbara Jakobson says. Before he came around to collecting photography, in 1973, Wagstaff, who had been a curator at both the Wadsworth Atheneum, in Connecticut, and at the Detroit Institute of Arts, championed the work of avant-garde artists like Tony Smith, Michael Heizer, Ray Johnson, and Agnes Martin. In 1964, at the Wadsworth, he put on the landmark exhibition “Black, White, and Gray.” The first ever museum show devoted to Minimalism, it sent a tremor through the art world and beyond: Cecil Beaton adopted its monochromatic palette for the costumes in George Cukor’s 1964 film My Fair Lady, which inspired Truman Capote to stage the Black and White Ball two years later, at the Plaza Hotel in New York.

Mapplethorpe may have grown up in a blue-collar neighborhood, but Wagstaff, who was 25 years the artist’s senior, knew his way around a society ball. “Sam gave Robert class, and Robert gave Sam sex appeal,” explains the curator Carol Squiers, who was Mapplethorpe’s friend and supporter. The Wagstaff family goes back to 18th-century New York. It owned swaths of land that would become Central Park and claims Edith Wharton as a relative. Sam Wagstaff’s mother, Olga Piorkowska, was a fashionable Polish émigré whose preference for New York society over the company of her children both pained Wagstaff and motivated him to succeed on his own terms. Piorkowska’s fashion illustrations appeared in Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, and she bred her son to grace the pages of the Social Register. When Wagstaff was not yet even a teenager, she taught him to smoke cigarettes so that she might have a handsome companion to tote around with her to parties.

It is no wonder that, in his 30s, Wagstaff, miserable and closeted, finally deserted the path that had been laid out for him—Hotchkiss, Yale, the Navy, a career in advertising—and made his way to the art world. (“It sounds as if I were a mechanical automaton,” he said of his life up until that point.) From then on, he would take a defector’s delight in making the members of his caste squirm. When the conservative trustees at the Detroit Institute of Arts demanded that Wagstaff pay for the damages incurred during the installation of a Michael Heizer earth work that mangled the museum’s lawn, he quipped to a local paper that it was “a triumph for manicured grass over fine art.” Ironically, it was the death of his mother, in 1973, that presented Wagstaff with the windfall that freed him to become a serious collector.

A year after meeting in 1972, Wagstaff and Mapplethorpe, who had been making mostly assemblage, collage, and jewelry, both turned their attention to photography, a field they found to be something of a desert. As Gefter points out, photos had begun appearing in the important art being made in the preceding decade—Andy Warhol’s grids, Robert Rauschenberg’s combines—but only “in the service of a larger conceptual idea.” It took a protean eye to see the medium’s full potential. “This was completely virgin territory,” John Waddell, a significant collector at the time, told The New Yorker in 1997. “Sam was a star, because he had so much art-historical reference that he could apply to looking.” Within five years, Wagstaff and a small circle of collectors had built a booming market for photography, extending the boundaries beyond Henri Cartier-Bresson, Eugène Atget, and the like to include the portraits of Julia Margaret Cameron and the innovative works of the 19th-century Frenchman Gustave Le Gray. As the collector Clark Worswick says in Wagstaff, “This is the man who set the aesthetic benchmarks for what’s good in photography.” Wagstaff knew what he liked, no matter who took the picture. His collection went back to the very beginnings of the medium and featured many anonymous vernacular masterworks. When the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., presented a show of Wagstaff’s collection in 1978, The Washington Post declared that it appeared that “the collecting of photography is socially acceptable; the Establishment approves of photography-as-art.” The critic added, “Sam Wagstaff is the artist that one most remembers after looking at this show.”

The exhibition opened almost exactly one year after Mapplethorpe’s own coming-out party. By then, his and Wagstaff’s relationship was evolving from a marriage of sex and art into one of friendship and patronage. Soon Mapplethorpe’s star would eclipse Wagstaff’s. The promiscuous photographer, whose increasingly dangerous sexual activity fed his work, wasn’t faithful in the way that Wagstaff might have wanted. Still, Wagstaff never stopped believing in him as an artist. Before Wagstaff, who had contracted AIDS, died of pneumonia in 1987, he sold his collection to the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, but he hung on to several Mapplethorpes.

That February night in 1977, just as the party at One Fifth was peaking, Wagstaff slipped out, retiring quietly to the penthouse high above the restaurant. His apartment had views that faced the two poles of his life: at one end, bohemian Washington Square; at the other, a sight line of Fifth Avenue. On the way up, Wagstaff stopped to check in on Patti Smith, who also lived in the building; she was bedridden after a fall during a concert. A decade later, when Smith visited Wagstaff’s bedside weeks before he died, he told her, “I have only loved three things in my life. Robert, my mother, and art.” It is a stupendous achievement—and a minor tragedy—that of the three, only art loved him back in equal measure.

Photos: Delayed Exposure

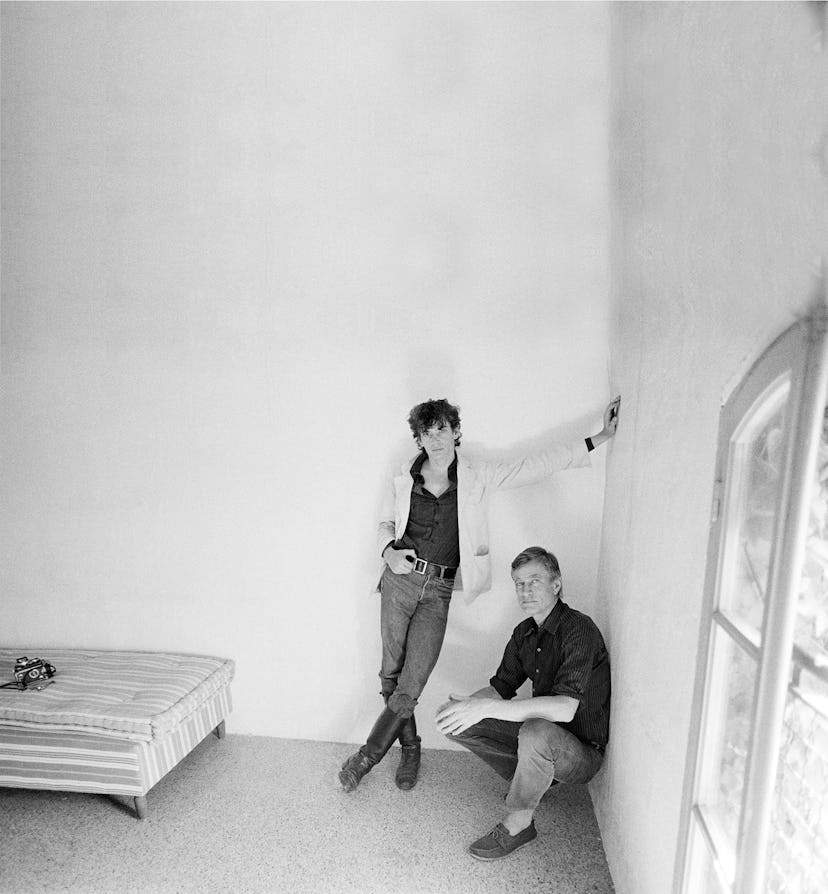

Robert Mapplethorpe and Sam Wagstaff, Arles, France, 1981. Photograph by Teresa Engle.

Sam Wagstaff’s Self-Portraits, 1973. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California.

Wagstaff in his apartment at Lafayette Towers, Detroit, 1970. Photograph by Enrico Natali.

Wagstaff at an Andy Warhol opening at Castelli Gallery, New York, 1964. Photograph by Billy Name.