The rediscovery of an artist is always endearing. It seems to happen every couple of years: An older painter with a sterling record, who has nonetheless escaped notice for a few decades,is suddenly taken up again. The work looks great, the artist is rescued from oblivion, andeveryone is bracingly reminded of how fragile and mutable our sense of history can be. It happened in the late ’90s to Bridget Riley; it happened a few years ago to Lee Bontecou. It’s happening now to Sam Gilliam, who is 81 years old and living, as he has for more than 50 years, in Washington, D.C.; and no one is more cheered by the rediscovery than he is.

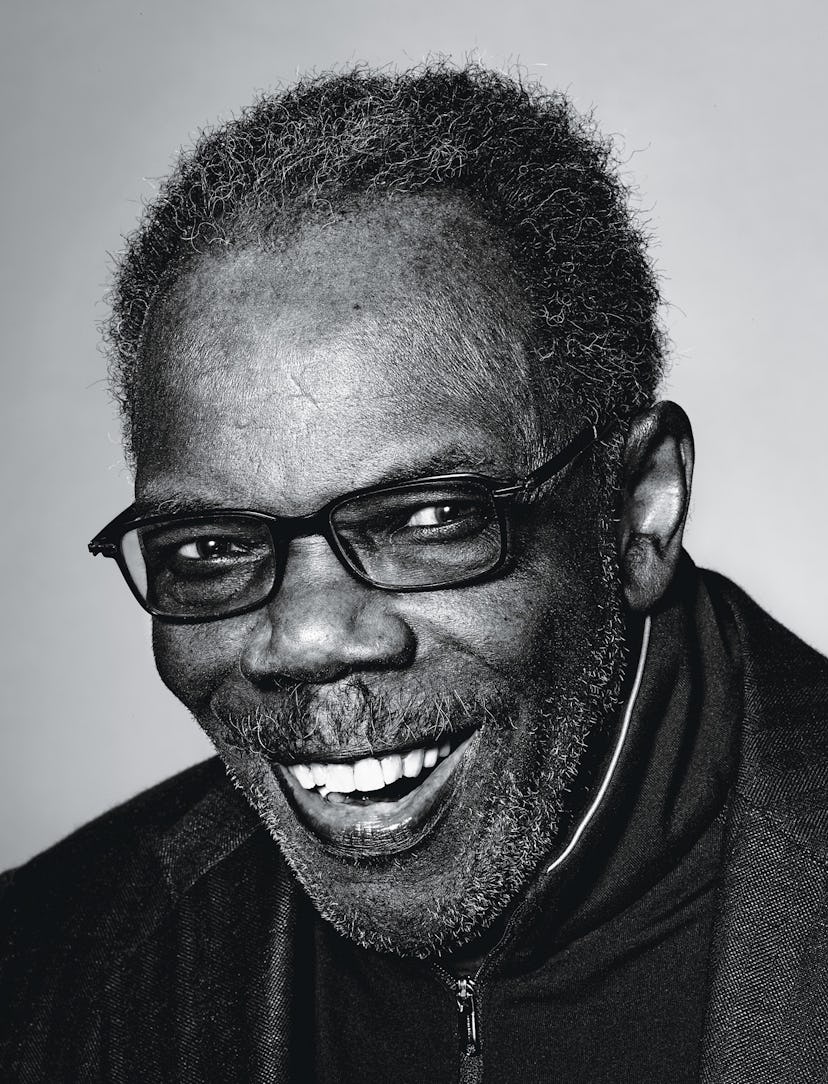

On a recent visit to his studio, a renovated gas station in the largely residential Petworth neighborhood, he comes to the door clad in standard issue artist black—a tall, slender man who moves as elegantly as a dancer. We sit, and Gilliam speaks softly, gently, thoughtfully, and with muted but evident emotion. He was born in Tupelo, Mississippi, one of eight children, and grew up in Louisville, Kentucky. To hear him tell it, he had an idyllic childhood, marked by just the right amounts of doting and benign neglect. The classic narrative of an artist’s life depicts a selfish man devoted to boozing and painting, a disappointed wife at home, and surly and estranged children. Gilliam’s is quite the opposite. In the early ’60s, his wife got a job as a city reporter at The Washington Post; he followed her to D.C. And while the marriage eventually ended, he stayed in town to be close to his three daughters and kept his studio hours strictly 9 to 5. “There’s an adjustment between being the father and being the artist,” he says. He smiles softly. “Anyway, ‘Dad’ is the sweetest word I’ve ever heard.”

Hanging in the studio are a dozen or so paintings, fashioned in the manner known as Color Field, a style thatinvolves pouring layers of acrylic paint onto unprimed canvases and letting it soak in. The result is an unruffledsurface that conveys a striking combination of flatness and depth. Like a lot of artists, what Gilliam loves to talkabout most is process: how the work is made, the properties of various materials, and the way the materials respondto handling. I ask him a banal and somewhat goofy question—What’s your favorite color?—and he answers with the sort of delight that most people bring to a list of their favorite movies, or songs. “Purple,” he says. “The purples, the blues. Purple colors have a depth. It’s just a romantic color. It’s royal. I used to never use greens; I used to be a great yellow person.” These things matter when the word “color” is in the very name of your triumph.

Gilliam is considered a third-generation Color Field artist (a “generation” in this kind of art history lasts perhaps four or five years), and he came to it obliquely, drawn inby his friend the late painter Tom Downing, who threw down a gauntlet. “I was painting figures,” Gilliam says. “I had a show of figural painting—sort of California school, Diebenkorn—and Tom Downing asked if I was afraid of art. He said, ‘Why not paint real paintings?’” He laughs. Gilliam was 28; had he, in fact, been afraid of art? He laughs again. “I’d always been afraid of art. I was afraid in college. But that fear is a goal, in a way: It makes you hesitate, and then you delay your start, and then you have a breakthrough.”

Gilliam started painting stripes—sharp, bright, and dynamic, in saturated colors, playing off Downing’s abstractions, and earlier paintings by Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland—and inspired, above all, by music. “Before painting, there was jazz,” he tells me. “I mean cool jazz. Coltrane. Ornette Coleman, the Ayler brothers, Miles Davis. It’s something that was important to my work, it was a constant. You listened while you were painting. It made you think that being young wasn’t so bad. All the young painters were into jazz.”

There are fewer solid firsts in art history than you might think—even within modernism,which made a fetish of innovation. One ofthe first artists to be known for pouring paint,rather than applying it only with a brush, was Joan Miró. From there, the technique leads to Jackson Pollock, and then HelenFrankenthaler, and then Louis. Gilliam has a first of his own, a breakthrough at least as important, if lesser-known—it came in 1967, a few years after the stripe paintings, and the way he describes it, it was almost an accident. He’d been experimenting with folding and creasing his canvases before he stained them, creating furrows and channels where the pigment would become particularlyconcentrated; he took the paintings off the stretcher andlaid them on the floor, turning them into something more like tarpaulins, which he worked from all four sides, creating a rosy, translucent effect, much like Chinese screens.“We used to talk about Coltrane,” he said in a 1984 interview with the Smithsonian Institution. “That Coltrane worked the whole sheet; he didn’t bother to stop at bars and notes and clefs and various things, he just played the whole sheet at once.” Gilliam was playing the whole canvas.

Gilliam’s Crystal, 1973. Photograph by Fredrik Nilsen.

In 1967, his old friend and mentor Walter Hopps—one of the great curators of last century—became the director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., and offered Gilliam a show in the rotunda. “He said, ‘I’m going togive you an opportunity,’” Gilliam recalls. “You’ll take theupper floor of the atrium, the space is 30′ by 60′, and you’ll paint. And these little paintings that you’re making won’t fit.’” In anticipation of the Corcoran show, Gilliam was in his studio working on a large painting called Niagara. As he was putting it on the wall, one side became dislodged, and the canvas fell to the floor. “I just thought, This is something,” he says. He began deliberately draping the canvases, creating fluid, semi-sculptural objects out of two-dimensionalpaintings. It was the first time anyone had taken a painting off the wall and transformed the cloth into folds and swaths and wraps, and they circumvented a whole series of formalpainterly concerns: the frame, the shape, the wall. What’smore, as powerful as the Drape paintings were, treating the canvas as malleable cloth rather than pristine surface was a nod to dress-making and window treatments, which undermined the machismo associated with painting in general, andAbstract Expressionism, in particular. For that—for all ofthat and more—Gilliam earned a place in art history.

This was a period of considerable recognition for Gilliam—he was included in the American Pavilion at the 1972 Venice Biennaleand had a major installation of Drape paintings at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art the following year. But then, as the’80s and ’90s arrived, with their hyperactive, theoretical, media-saturated art scene, Gilliam went into eclipse. Though his work redoubled in density and complexity, the world’s attention didn’t follow. There was a retrospective at the Corcoran in 2005, and then nothing. In part, that’s the natural cycle of history: Ways of working come and go. In part, too, it was because Gilliam had veered away from the Color Field painting thathad brought him to prominence, reversing its emphasis on flatness by making his work almost architectural. He’d been looking into origami and string games, like Cat’s Cradle, for inspiration—these were heresies. Painting in the 1960s was meant to be a terminal affair, the moment when the entire history of painting absorbed all its own verities: image, surface, brushstroke. As his current dealer, David Kordansky, puts it, “Color Field painting, as brilliant and amazing as it was, to some extent was kind of endgame painting. Where Gilliam is very different is that for him, it was just the beginning. He was looking for new ways to experiment and push painting forward.” The style couldn’t hold him—he would put down a body of work and then circle back years later and resume it. That made him hard to track, hard to categorize. And so did his reluctance to treat his race as significant to his art. “It’s not,” he tells me. “It’s important to me as a man, but to the work, no.”

There followed years in the wilderness—regular shows in a loyal D.C. gallery but little public recognition. And there were personal struggles: Gilliam suffers from bipolar disorder, a fact he speaks of openly. He spent decadeson Lithium, which damaged his kidneys and eventually left him in a depression so severe that for three years he scarcelyleft the house; he’s been off the drug only a few monthswhen we meet. But even as he was working his way through the darkest times, things were starting to happen for him. He was included in group shows, in museums, and, in 2012, at Gladstone Gallery. Around that time, Kordansky, a longtime admirer of Gilliam’s work, flew to D.C. to meet him. He immediately asked for a show; the artist wept at the offer (Kordansky says he came close to doing the same). His first solo exhibition took place at Kordansky’s gallery in Los Angeles in 2013, a selection of early, Hard-Edge paintings curated by gallery-mate Rashid Johnson. “The interest,” Kordanksy says, has been “kind of mind-blowing.” In the past year, both the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have acquired Gilliams—in the first instance, a spectacular, tripartite Drape painting from 1969; in the second, a bright multicolored bevel-edge painting from 1970. Several major private collections have also bought pieces. At the same time, Color Field is making its own comeback, with shows in New York of work by Louis and Frankenthaler, Jules Olitski, and Kenneth Noland, all in this year alone.

As for Gilliam, this is his moment, and one can’t help but enjoy it with him. His work is pure, a relatively rare thing in this day and age, but more than that, he’s a gentleman (though I’m sure he’s quite capable of being irascible), and his happiness seems hard-won. This is what we want artists to be: ambitious but not vulgar about it, original but not gratuitously so, confident but not immodest, and, above all, in love with their medium. This is what we want to hear: that sooner or later, the prophet gets the honor he deserves.

Digital technician: Nic Herrera. Photography assistants: Kim Reenberg, Enrico Brunetti.