Roni Horn

Who is Roni Horn? For years, the artist has been asking that very question herself, exploring notions of perception and identity through sculptures of pure gold, photographs of taxidermied bird heads and installations of melted glaciers.

Roni Horn’s subtle but commanding art demands a focused eye to be seen for what it is. The same can be said for Horn herself. With the exception of her eyes, which are the brilliant blue of a far-off sea, she is almost devoid of color. Her salt-and-pepper hair is shorn so short as to blend with her pale face. Her mannish black shirt and jeans add to the effect, further deflecting snap judgments. A quick glance at Horn on the street or in a restaurant would yield few conclusive clues to her gender, so complete is her androgyny. She must be looked at.

Her art, too, is unconstrained by convention; it’s always a notch off-kilter. Rooted in conceptualism but deeply intuitive, with influences as varied as Iceland’s primeval terrain and Flannery O’Connor’s Southern Gothic short stories, her oeuvre spans mediums from photography and books to drawing and sculpture. There is, for example, Asphere (1988), balls made of stainless steel or copper with dimensions just a bit tweaked—they’re not quite spheres. Then consider Her, Her, Her & Her (2002–03), a collage of black and white photographs shot inside a women’s locker room, mostly of tile and doors but with voyeuristic glimpses of women, and Things That Happen Again: For Two Rooms (1986), two copper cylinders placed in two separate spaces. They seem to be identical, but since the viewer can’t see them simultaneously, who’s to say? “I don’t necessarily think of myself as a visual artist primarily,” says Horn, 54. “A lot of my work is really very conceptual, and it has very little visual aspect to it, the sculpture especially. That work is more powerfully about experience and presence than it is about a powerful visual experience.”

Unlike the artists who made themselves into brand names over the past two decades, Horn has steered clear of a signature style. She avoids instant, easy identification while cleaving to themes of identity and nature. “Her work requires silence,” says Vicente Todolí, director of the Tate Modern in London, where Horn’s midcareer retrospective, opening November 6 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, originated. “It makes you aware of your condition as an individual and confronting the world. And that is not easy. It can take some loneliness. On the one hand, you can feel related, involved, attached to the work, but at the same time, the lines or the threads are almost invisible.”

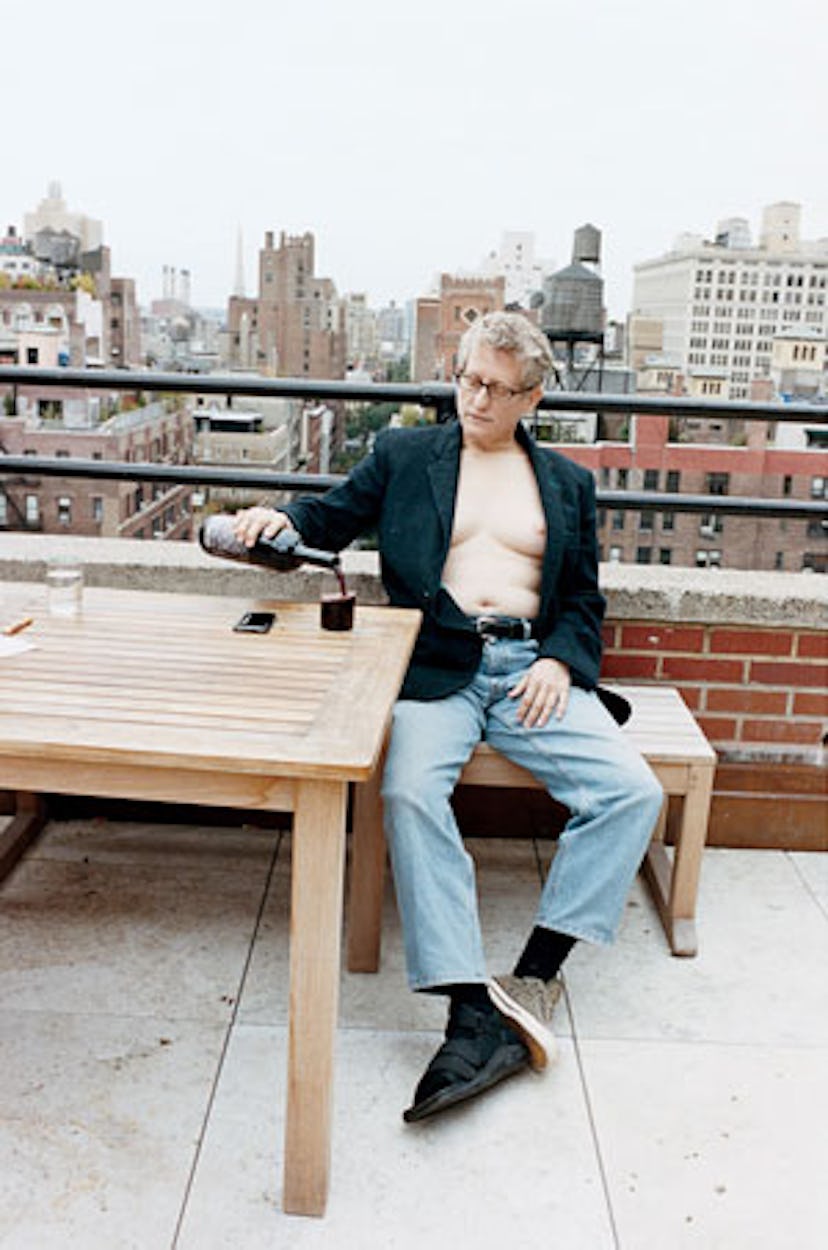

On a warm July afternoon, sunlight is pouring into Horn’s expansive studio in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. She has pulled her chair close to a window overlooking a courtyard and a spectacular flowering mimosa tree. Horn, drinking a glass of water, is warm and funny, self-deprecating while not feigning modesty as she talks about the retrospective and its catalog, an unusual two-volume set that encompasses her thoughts on all manner of topics, as well as the standard color plates of her greatest hits. On one cover is a matching pair of photos of Horn wearing horn-rimmed glasses and a white button-down shirt over an undershirt. She took some heat for the choice. “There wasn’t really any narcissistic element,” she says. “Nobody would know that’s me, per se. But there was some criticism about ‘You shouldn’t do that, Roni. People will think the book’s all about you.’ Yeah? Well, the book is about me. Eventually they changed their minds, I think. Regardless, I overrode those questions.”

The portraits are part of a work titled a.k.a. (originally published in W’s 2008 Art Issue). There’s one of an adorable freckle-faced mop-top with a winsome smile and another of a budding intellectual circa the 1970s. Not even her closest friends and family, Horn says, initially realized the snapshots were all of her. Referring to a picture in which she appears a wildly frizzy-haired creature, her body obscured by an Icelandic moonscape, she marvels, “It’s weird how much I look like Iceland.” As her visage ages, the subject grows increasingly androgynous. It’s as if Horn’s life were a performance piece.

The granddaughter of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, Horn was named for her grandmothers, both of whom were Rose. Even as a child in the Sixties she was convinced the gender-neutral Roni gave her an advantage. “When I was young I decided that my sex, my gender, was nobody’s business,” she says. She didn’t know much about her family history; it was only after her father’s death that she learned his given name was Abraham, not Arthur, and that his own father had been a buttonmaker. Arthur owned a pawnshop in Harlem and moved his family upstate, to Rockland County. “It was farmland at the time; it was an early suburb,” says Horn, the third of four children. “When I was growing up, there was only one bookstore in the whole f—ing county.” There were not many Jews, either. “I have this memory of my Girl Scout [leader] quitting when I was assigned to the group—it was just anti-Semitic.”

Still, Horn is not sure how credible her recall is. “I’m fascinated by eyewitness accounts,” she says. “It’s always so perverted, or altered, by who you become. It’s so hard to say what really happened. So when I talk about myself, I don’t believe a word of it. I’m not a fabricator, but I’m very skeptical.” She has even considered making an autobiographical film told from the perspective of eyewitnesses to her life. When I note that I might prefer not to hear what others have to say about me, she quips, “Well, maybe that’s why I haven’t done it yet!”

Her interest in perception helps explain her tendency for pairing objects. At the very least, they force the viewer to do a double take: Are the images the same or a hair different? Doubling, she says, is a way “to engage people. You know, an artist is always manipulating. That’s what the name of the game is, really.” Later she points out a piece hanging in another room. “It’s a double Möbius, and I just love that paradox, double infinity. What the hell is one infinity? Now you’ve got two infinities. It’s almost like the double negative. It has this funny feeling of amplification, but of what?”

Horn says she didn’t need to “figure out” that she was gay. “Consciousness—when does that start? Who the hell knows?” she says. As for her family, “who knows what they knew? Nobody said anything. It’s not something to talk about.” But she adds that her sexuality was “probably why I left them, went to school so early. I’m sure that fed into it.”

Whip-smart, Horn fled high school at 16 and enrolled at the Rhode Island School of Design, which gave her a year’s worth of credits, “so it was a fast jaunt,” she says. She graduated at 19, and she flew to Iceland. In the Seventies, budget travelers routinely went to Europe by way of Reykjavik because of the cheap fares, though for most it was just a layover. Camping in a tent with her then girlfriend, Horn was knocked out by the landscape and the perpetually unstable weather. “I had the need to keep going back,” she says. “It wasn’t a conscious thing—it was more like a yearning. I always think of it as a migration because I prefer to keep my metaphor with the animals, and I had that sense of physiology to it.”

Though Horn had tinkered with cameras from her dad’s pawnshop, she was no more than a self-taught photographer, but Iceland inspired her to make photographs. With its weird volcanic landscape and primordial glaciers, the country would become her muse, or, as Todolí puts it, her El Dorado. “The cloud cover was always low,” Horn recalls. “You couldn’t really see—you just saw a tease. So I really believe that for a good 10 years or so I was going back to see a little bit more of what I couldn’t see.”

Among her large body of Icelandic-based art is an ongoing series of books, now numbering nine, titled To Place. Armed with a telephoto lens, she made You Are the Weather (1994–96), consisting of 100 photographs, all tight shots of a sole model’s face gazing directly at the viewer as she stands neck-deep in myriad indistinguishable pools and streams. The nearly imperceptible differences in the model’s expression—primarily a little less or a little more squinting, a slightly tilted head—are a reflection of the ever-changing weather. The viewer thus takes on the role of the weather. (“You Are the Weather, that’s a f—ing good title, girl,” Horn muses.) It’s a favorite piece of Whitney chief curator Donna De Salvo’s. “The faces require this incredibly acute and precise eye,” she says. “They really draw you in.” Artist Matthew Barney, a friend who also happens to be a frequent visitor to Iceland (by dint of his relationship with Björk), says Horn’s work “appears more formal than it is. In fact, it’s highly emotional.”

Horn’s latest project in Iceland is Library of Water (2003–07), which houses an installation in a former library in the small town of Stykkishólmur. Glass columns hold melted ice from 24 Icelandic glaciers. Inscribed in the rubber floor are words such as “cool” and “moist.” “They’re all adjectives which could be used to describe weather conditions outside in the world,” says James Lingwood, whose Artangel organization raised money to produce the piece, “but also inside, you know, in you.” Though it will clearly go down as one of Horn’s iconic works, orchestrating it altered her relationship with the country, perhaps permanently. “I had kept very much to myself for years and was just out photographing or walking or thinking,” she says. With Library of Water, though, she couldn’t simply retreat into the landscape; it was a “social experience,” she says, that required her to deal with an extensive team of people—and intruded on her private communion. “I think my needs have changed,” she adds. “For me to hold on to that relationship to Iceland would have been making me a tourist of myself in a way. I can imagine going back, and I will, but it’s not like a yearning.”

In retrospect, Horn says, Iceland started to feel “less compelling” once foreigners started visiting in droves in the mid-Nineties. “Maybe a lot of Iceland was just about me being inexperienced,” she says. “I sometimes wonder if the first place I hit was Italy, whether Italy would have been my Iceland. Iceland is great for weather and solitude, but food is a problem. Italy is definitely more my thing for food.”

After her inaugural trip to Iceland, Horn worked for a year before matriculating at Yale for graduate school, “because I was very young,” she says, “and I was trying to, you know, get old. The problem with being precocious is that your connection is with the older generation because that’s your mental generation. You’re in this awkward relationship to your peers.”

At Yale she entered the sculpture department. “It’s not because I thought, Oh, sculpture, great,” she says. “I was always much more interested in painting. But I think when I went to Iceland, that helped me understand what my intuition was about. One of the things that interested me was that sculpture wasn’t a medium, and so you have pretty much all the mediums available to you, unlike painting. Painting is paint.” While at Yale, Horn also began her drawing practice, which she describes as “absolutely essential to me, although not to my viewer. My drawing was always about my relationship to it, not the audience’s.”

Artist Robert Ryman, whom Horn met at Yale, tipped off a German curator to her work. Ever since, she has had a stronger following in Europe. Until the September opening of London-based Hauser & Wirth gallery on the Upper East Side, she had been without New York representation for four years. Fiercely independent, Horn has self-financed much of her work. To raise the money to produce Gold Field (1982), a haunting sculpture of a micro-thin sheet of gold that, when folded over itself, gives off an orange glow akin to a burning flame, she admits she labored briefly for a “seriously shady” businessman. “The way I looked at it was, it would be worse if I wasn’t able to do this piece than to deal with the consequences of these actions if I should be caught,” she says. “I feel that these [artworks] should really be out in the world. Look, I didn’t have close to that kind of money to produce it, and I didn’t know anybody to ask for it. I had nothing. I just knew I had to do this.

“When I was really young I made a commitment to myself that money would never be a factor in inhibiting my options,” she continues. “I just managed to get things done no matter what.”

That kind of determination has earned Horn a reputation for single-mindedness. Every colleague and friend interviewed for this story mentions her precision and exacting standards. “She knows exactly what she wants,” Barney says. “She’s very clear. Very, very clear. She’s willing to hold out to avoid compromise.”

When it comes to dreaming up a piece, though, Horn says she relies heavily on her gut; it’s not all plotted beforehand. “It’s a lot of open-ended things that evolve,” she says. She began photographing Bird (1998–2007), a series of starkly compelling taxidermied bird heads, some seen from behind and veering into abstraction, while scouting for another piece, without any clear idea of what to do with them. “If it’s still kind of itching at you over a period of time, you’ve got to deal with it. It’s very subtle, actually, the point at which an idea becomes something worth pursuing,” she notes. Humor also comes into play: Clowd and Cloun (2000–01), alternating photographs of a clown’s face and puffy white clouds, “started as a misunderstanding of [the Stephen Sondheim song] ‘Send in the Clowns,’” she admits wryly, adding in her defense, “I did a poll, and a lot of people thought it was ‘Send in the Clouds.’ So I wasn’t alone.” The odd spellings, she says, are archaic, “but they’re also this wonderful crisscross of identity.”

Horn’s subjects may range from water to gold, but the mystery of identity is what lies at the heart of her oeuvre. She has called Asphere a self-portrait. “You go in thinking you know what you’re looking at, but it isn’t,” she says. “But it’s not really anything else, either.”

Therein lies Horn’s genius, in De Salvo’s mind. Even her choice of materials can toy with the concept of identity. Citing Horn’s cast glass sculptures, De Salvo notes that glass may appear to be a solid but is actually always a liquid. Horn is consistently “really questioning what something is,” De Salvo says. “Is it one thing, or is it another?”

Horn was close to the artists Félix González-Torres and Donald Judd, who was an early booster, before their deaths. She has an impressively accomplished circle of friends today, among them Helmut Lang, Douglas Gordon and Juergen Teller. Lang describes her as “straightforward, witty and incredibly loving.” But Horn insists, “I’m not a very social person. I’m outgoing when I have to be, but where I like being is alone. I love the solitude in my studio.” There it’s just her and her thoughts. Asked if, despite her reputation for confidence and certitude, she ever struggled to find her voice, she laughs. “Oh, for about 20 years,” she answers. “I don’t think it was ever really easy for me. It was an endless chasm of doubt. Full, full of doubt.

“There’s still a lot of doubt, definitely,” she adds. “But now I have probability on my side.”