In Bed With Roberto Cavalli

Lauren Collins checks in at Casa Cavalli—complete with a mouth-kissing monkey, a Persian cat named Pussy, and an iridescent purple helicopter—and lives to tell the tale.

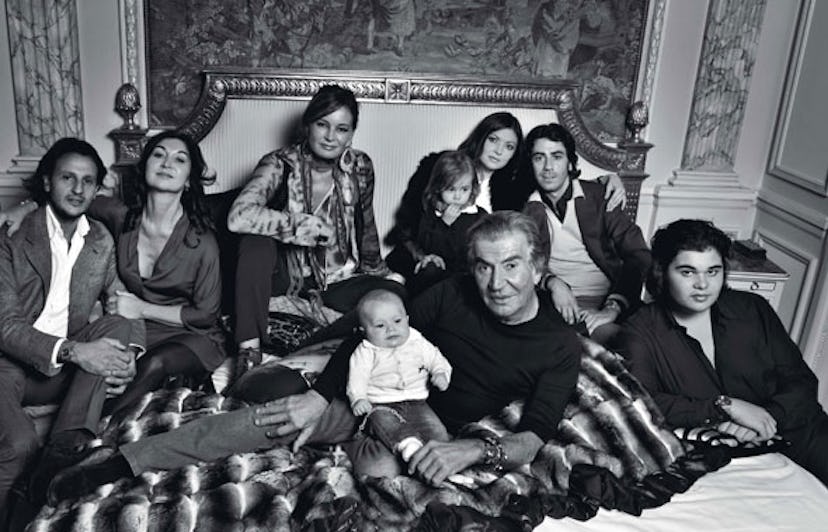

Roberto Cavalli walked in the door of his house on a recent Friday night and slung a black leather bag onto a chair—a salaryman, settling in for the weekend, in tight jeans and Cuban heels. He pushed his aviator glasses up the bridge of his nose and ran a hand over a gray-stubbled cheek. The day’s commute had been long: He’d flown from Jordan—where he attended Queen Rania’s birthday party—to Milan, and then home to Florence in his iridescent purple helicopter, the Cavalli equivalent of Metro-North. Now it was 10 p.m., dinnertime in Italy, and the table was set. Assorted Cavallis—his wife, Eva; their children Daniele, 24, and Rachele, 27; Cavalli’s daughter from his first marriage, Cristiana, 45; and a slew of significant others and grandchildren—were ready to talk and argue and drink and feast. But Cavalli, not willing to surrender the attention his homecoming had afforded, was brandishing a souvenir from his travels: a pair of pink plastic Barbie mules, edged in marabou, and a matching pink plastic Barbie cell phone. “Vuoi un regalo?” he said, drawing close to Rachele’s two-year-old daughter, Maria Eva, and enveloping her in a bear hug. She nodded. Cavalli knelt down low, placed the shoes on her feet, and showed her how to dial. “Amore, dammi un bacio,” he said, exacting his tribute.

The Cavalli estate occupies 36 undulating acres on the city’s outskirts, with indoor and outdoor swimming pools, a wine cellar, and a helipad. In addition to the main house, there’s a futuristic bachelor’s studio, built in 2008 by architect Italo Rota, with a tanning bed, a DJ booth, and a bed laden with stuffed animals. (The family also owns a 134-foot yacht, the RC.)

Cavalli began his career as a fabric printer, and above all else, he is famous for slathering animal prints on everything from red-carpet gowns and espresso cups to doggie clothes. Some find this delightful (“I wear him right down to my underpants,” the London-based retailer Mohamed Al Fayed has said), others distasteful (The New York Times likened his 2007 collection for H&M to “what you might find under the ‘streetwalker’ section of the costumes on sale at Ricky’s”). At Casa Cavalli there are enough animals, real and simulated, to rival the Serengeti. On the patio four parrots shrieked in their cages, recalling a medieval torture chamber. Cavalli keeps a miniature monkey (he has been known to kiss it on the mouth) and a giant, coddled Persian cat. “Do you know the name of my cat?” he asked. “Pussy! It doesn’t mean what you think—I am much more clean—but I tell you, she is very sexy!”

The Cavallis take pleasure in taking pleasure. They are the rare rich family that appears to actually enjoy itself, rather than merely accumulating the accoutrements by which it might. “When I go to a restaurant and they say, ‘We’re fully booked,’ I say, ‘It’s Roberto Cavalli,’ and they say, ‘I will check,’” Cavalli said, clapping his hands with relish. “I love it!” (The other great perk of fame, he said, is getting his doctor to make house calls.)

The family’s habitat is opulent but unfussy—less a still life than a music video. Incense filled the air; oranges, draped with strands of pearls, sat on a chunky silver cake stand. The room where I’d been invited to spend the night was a surprisingly cozy, wood-beamed in-law suite. There was the requisite leopard-print bedspread. But there was also a winningly uncurated selection of books and knickknacks and a medicine cabinet full of random ancient toiletries. Wandering by the pool I noticed an empty bottle of limoncello wedged into the hull of a tiki torch. In the parlor a table, upholstered in green velvet and surrounded by Philippe Starck chairs, was set up for poker. All the vices were covered. If the Rockefeller family motto is “None are more faithful,” the Cavallis’ might be “None are more fun.” The overall effect was something like the House of Usher crossed with Club Med.

Cavalli, who turned 70 in November, is an old-fashioned capofamiglia—not just the head of a $250 million fashion company, with 65 stores in 23 countries, but also the sire and cynosure of a tight-knit clan, the vital provider whose every wish must be met. “His personality is very strong,” said Cavalli’s son Tommaso, an unassuming father of three who runs the family’s stables and vineyard in nearby Panzano. (He was absent from the aforementioned dinner because he was entertaining clients. Likewise Cavalli’s youngest son, Robin, 16, who was away at school.)

Tommaso displayed on his desk a framed photograph of himself as a boy with his father, on which Cavalli had written, “My eyes follow you, little big man.”

With the exception of Tommaso, all of Cavalli’s adult children have gone into the family business, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. Cristiana manages the company’s budding hospitality arm, Rachele leads the accessories division, and Daniele works on the men’s wear team. It was always obvious to Cavalli that he would have a family—it is only surprising, given his love of women, that his fruitfulness has remained more or less linear. “I tried immediately to have a baby because I was so afraid not to have a baby in my life,” Cavalli said, settling, kinglike, into a baroque leopard-print chair. “My first child was born nine months, 10 days after the wedding. For me, I would expect to have 10! I never understand why God give the possibility to have children just to woman,” he continued, clutching theatrically at his belly. “Oh, my God, my dream would be to have a baby!”

Eva, by contrast, is understated and reserved, emanating a quiet self-possession. She met Cavalli in the Dominican Republic in 1977. He was a judge at the Miss Universe contest; she, an 18-year-old Miss Austria, was first runner-up. Shortly thereafter she drove from her home in Austria to Florence in a sky blue Citroën convertible, her prize from the pageant, and never left. The pair married in 1980, and she has been Cavalli’s business partner, collaborator, and all-around helpmate ever since. Speculation about the state of the couple’s marriage has swirled around the fashion industry in recent years (the construction of Cavalli’s bachelor pad hasn’t helped), but the pair, like Renaissance monarchs, present a united front. Whether or not the romance has cooled seems less important than the fact that they remain committed co-rulers of both the family and the empire.

The reigning sensibility at Casa Cavalli is a sort of Proustian maximalism, a memorialization, in lamé and Lycra, of hot things done by cool people in warm places. For the dinner Eva had transformed the family room—where crucifixes and Madonnas mingle with a flat-screen TV—into a sort of pop-up dining room, draping a tapestry-print sheet over a sprawling square coffee table and decorating it with all manner of bric-a-brac: tusks, ashtrays, crystal balls, sprigs of ceramic coral, lizard figurines, palm tree candles, bedazzled crabs and shells. The centerpiece was a golden orb that brought to mind the World Cup trophy. A fake peony sat next to each gilt-rimmed plate. Eventually, one of the Barbie mules ended up on the table; it did not seem discordant. “I never like to eat in the same place,” said Eva, who once staged a dinner party in the family’s steam room. “I like to have lots of things around, because they instantly remember me something.”

Cavalli is a man of appetites. He loves racehorses and soccer. He speaks of women in an exuberant, connoisseurial way, as a particularly passionate collector might discuss baseball cards or model cars. As plates of pasta emerged from the kitchen (“Eat with me!” he commanded. “I don’t want to be the only one who becomes fat!”), the conversation progressed from reproduction to past loves. His first marriage, to Silvanella Giannoni, the daughter of a wealthy Florentine, ended in 1974. “I was 18; she was 20,” Cavalli recalled. “I think I give her the first kiss after six months. But I was not innocent—we would go in my Fiat 500! We make love when we married. I remember the first night, our wedding.”

Puffing on an electronic cigarette as the rest of the guests smoke Murattis and Marlboros—by now the room resembled a miniature Eyjafjallajökull—Cavalli began to reminisce about his childhood. When he was 10 years old, he was infatuated with a neighborhood girl. Every day he would follow her to the tram, but he never had the courage to reveal his feelings. Last year, he said, he was watching a television show that reunited contestants with people from their pasts. “Sometimes I think I would like to be on that show,” he mused dreamily. “The long black hair! The skirt down to here, with flat shoes. I remember what kind of bra she use! Is my first erection!”

Eva, who grew up in a middle-class family in the Austrian town of Dornbirn, is the practical enactor of her husband’s visions, the straight woman to his romantic jester. “I come from a very simple family,” she said. “This, what we are living now, is very complicated. When my father came here, years ago, we had dinner one night, and he said, ‘Eva, what is happening? I’m worried. What is all this shouting?’ I said, ‘Don’t worry. Everything is fine. We are just talking.’”

As a parent she is the cool, rational crust to Cavalli’s volcanic, emotional core. Said Cavalli: “Sometimes, because of my success, I am afraid that I was not a good father. With the first two I was too strong, and with the other three I was too weak. I told Tommaso, ‘Take a Ferrari and go to Monte Carlo!’ He said, ‘If I drive a Ferrari, it will be when I am able to buy it myself.’ I say to myself, Okay, Roberto, maybe you were too strict. But Daniele, he take everything. He destroy my Porsche in the highway!”

Cavalli, an inveterate gossip, regaled the table with news. “I saw him kissing another guy!” he said of the husband of a gay celebrity. And remarked on his 40th-anniversary show, which was to take place in two weeks in Milan: “I will invite the other designers, but they won’t come—they are all shit.” Eva, who has been working 15-hour days—while Cavalli was partying in Petra, she had passed out in front of the television, fully clothed—seemed more stressed than he did about bringing off the show. The children talked mostly among themselves. Rachele’s younger daughter was to be baptized the next morning at the Basilica di San Miniato al Monte; Cristiana was pregnant with her first child by her fiancé, Francesco Agostinelli. “They’re not married!” Cavalli exclaimed as the table went quiet. “As an Italian father, I say, ‘How dare you?!’”

“I don’t like big marriages,” Cristiana said.

“It doesn’t have to be a big marriage,” her father replied before breaking into a mirthful baritone. “I’m joking! I’m joking! Do what you want!”

Cavalli was born in a suburb of Florence in 1940. His maternal grandfather, Giuseppe Rossi, was an Impressionist painter of some renown. (His work is on view in the Uffizi Gallery, and also in the Cavalli poker room.) His mother, Marcella, was a seamstress, and his father, Giorgio, worked as a surveyor for a mining company. On July 4,

1944, Giorgio was killed by German soldiers, the victim of a retaliatory attack against the Italian Resistance. Young Roberto developed a stutter. He was shy and unfocused in his schoolwork. “I was a disaster child,” he said. “I remember I make very often my mother cry.”

Like so many successful Italian men, he was motivated to make something of himself by his deep hunger for a Ferrari. (He has three now, along with a zebra-striped Ducati; Eva drives a sensible Audi.) As a teenager, Cavalli entered the Istituto d’Arte in Florence, where he studied textile design. Soon he was zipping back and forth to the textile workshops of Como, where he developed a technique for printing on sweaters, a novelty at the time. Krizia and Hermès placed orders. By the end of the Sixties, he had figured out a way to print on leather, attracting more prestigious accounts. Cavalli, who conducts his affairs from a 15-year-old Nokia cell phone the size of a shoe (“I bought all of the ones on eBay,” he said), is more of an ideas than a details man, and he prefers to concentrate on the creative side of the business, leaving much of its day-to-day operation to Eva and to Gianluca Brozzetti, the latest of several CEOs. (In 2003 Cavalli went on trial for tax evasion, and was convicted in 2006. He received a 14-month suspended sentence.) In 2005 the company hired a general director, Roberto Jorio Fili, who quit after little more than a year, comparing the experience to a marriage that “was never consummated.” Cavalli’s take on management is casual. “Sometimes incompetence is useful,” he once told The Wall Street Journal. “It helps you keep an open mind.”

Prints—some so intricate as to resemble mosaics—remain the heart of Cavalli’s identity. He is one of only a few designers who maintains in-house printing operations rather than outsourcing the process. Whereas less exacting factories will print many colors at once, causing the pigments to blur, Cavalli’s craftsmen run each piece of fabric through a dyeing machine seven times, a painstaking process that results in the crisp, deep patterns his customers crave. Recently, Cavalli has taken to obsessively cataloging images, most taken from nature, that catch his eye on his digital camera. “It is always about the animal,” Slobodan Mihajlovic, Cavalli’s knitwear designer, told me. “You always have to be ready to find an animal—or even to come up with a new one.” Having exhausted the bounty of the world’s skies and savannahs, Cavalli has invented ligers, snish, and beetleflies. “The leaf of every flower is like a fingerprint,” he told me.

Cavalli presented his first fashion show at Porte de Versailles in Paris in 1970. By 1972 he had opened a boutique in Saint-Tropez called Limbo; Brigitte Bardot and Sophia Loren were fans of the boho-luxe leather jackets and crocheted silk sweaters. But the Eighties, with the advent of power dressing, were an unhappy and unprofitable time for Cavalli. He retreated into obscurity. He thought about shutting down the business. Even now he talks about the era as though it were a moral crime. The Working Girl look, he said, “tried to destroy the femininity of a woman. It try to make the woman feel like a man, to feel important.” Happily, his luck changed in the Nineties—thanks in part to the development of Lycra. In 1993 he began working it into denim, a technological innovation that many women of the era deemed right up there with the Hubble Space Telescope. (If jeggings are second-generation stretch jeans, then Cavalli actually has not five but six grandchildren.) Then, in 1998, he met Franca Sozzani, editor in chief of Italian Vogue, at the Ritz Hotel in Paris. Cavalli asked for her advice, and Sozzani suggested that he approach Anna Dello Russo, who was fashion editor of Italian Vogue at the time, to consult. “I met Roberto and Eva in Florence, and I was surprised to learn that Roberto Cavalli was about prints and not just leather,” Dello Russo recalled. “They started doing clothes made for Hollywood. In 10 years Cavalli became important for the red carpet.”

In the interest of keeping the company flourishing, Cavalli has always been happy to take help where he can get it. “To keep up with the tam-tam of fashion”—he mimics a drumbeat—“we need help from stylists. For Armani, is enough to change one lapel on one jacket. From us the people expect new design, new style, new way to attract the new boyfriend.”

And so, in Milan, the night before the 40th-anniversary show, the Cavallis convened again, in the company’s showroom on Via Senato. The air of a cram session prevailed. Blinds were drawn. Shoes, coffee cups, cell phones, and half-naked skinny people were strewn everywhere. Cavalli sat with Eva and Rachele near a makeshift catwalk, drinking white wine and debating last-minute alterations. “We are in a hard moment,” Eva said. “I don’t know why it happens that we are so late all the time.” By the next morning, however, everything was in place. The Arco della Pace, a neoclassic arch commemorating the unification of Italy, had been bedecked in mirrored tiles, like a disco ball—a monument Cavalli-fied. Half an hour before the show, Cavalli was perched atop a pair of white cubes, greeting well-wishers and dignitaries. Behind him giant gold palm fronds and metallic pepper plants loomed.

Soon, to thunderous bass beats, the show began, a retrospective of trompe l’oeil effects (leather feathers, sequined hides) and artisanal details (laser-cut leather jackets, laced bodices reminiscent of Florentine bookbinding). The clothes—low-slung, whipstitched trousers and webby cutaway gowns in a simple palette of gray, black, and bone—were strong but not bombastic. Natalia Vodianova and Laetitia Casta made valedictory appearances on the runway as Rachel Bilson, Taylor Swift, and Leona Lewis watched from the front row. When it was all over, Eva seemed relieved. Cavalli, blowing kisses and cocking thumbs at photographers, was ebullient. “We both love fashion, and we both love the woman,” an Italian reporter said to him backstage. “We are the best, we are the best!” Cavalli replied. “The next will be 50—I promise, I will be here with you!”

Eva was smoking a Muratti and drinking a glass of white wine. “There are lots of emotions,” she explained. “I was in Austria for my mother’s 90th birthday last month, and she got out some pictures of me and Roberto from 30 years ago.” What did they make you think about? I asked. “How beautiful we were.”

A couple of days later, in Paris, the celebration continued. At the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, people in jungly tribute outfits lined up around the block. Inside, among the Michelangelos, a tableau of mannequins were outfitted in Cavalli’s greatest hits, and guests dined on caviar, risotto, champagne, and prosciutto, shaved on a Berkel meat slicer just like the one in the Cavallis’ kitchen. A burlesque troupe performed, as did Kylie Minogue. As confetti rained from the rafters, a woman jumped out of a towering cake. “You have such a vision,” Heidi Klum yelled into a microphone. “You make us look so beautiful, and I know the guys don’t mind either. Roberto Cavalli!”

In Florence, as the family dinner wound down, Cavalli had mentioned that, late at night, he was writing a sort of memoir. His life in fashion was part of it, but more important to him was the way he had fashioned his life. “I don’t know what to write in the last 15 years,” he said. “What model I have in my fashion show?

“I have so many dreams,” he continued. “I design an unbelievable rubber boat. And I was thinking, with this big dinghy, maybe to arrive in India by myself.” You must be joking, I had replied. Cavalli took a drag on his cigarette and looked me in the eye. “How much you bet?”

In Bed With Roberto Cavalli

Roberto Cavalli’s silk macramé dress; suede and metal hairpiece, necklace, and bracelets.

Roberto Cavalli’s silk chiffon dress; suede and metal hairpiece, bracelets, and necklace.

Roberto Cavalli’s embroidered silk dress and python bra; suede and metal hairpiece and bracelets.

Roberto Cavalli’s silk chiffon and suede dress and crocodile and python jacket; suede and metal hairpiece, necklace, and bracelets.

Hair by Sam McKnight; makeup by Gucci Westman for Revlon; manicure by Yuna Park at Streeters. Model: Frida Gustavsson at IMG. Photography assistants: Jimmy Mettier, Fred Bealet, and Gael Bouryneau. Fashion assistant: Kathy Lee.