Rhett Butler Gives A Damn

If it weren’t for high-end-hardware impresario E.R. Butler, reports Corey Seymour, untold architectural treasures would be gone with the wind.

It’s quite possible to visit the Prince Street showroom of E.R. Butler & Co., in New York’s NoLIta neighborhood, and have no real grasp of the company’s essential business. Four enormous vitrines containing a rotating collection of tableaux vivants occupy the building’s front windows, and would seem to indicate some eccentric admixture of gallery, boutique, and high-end jeweler.

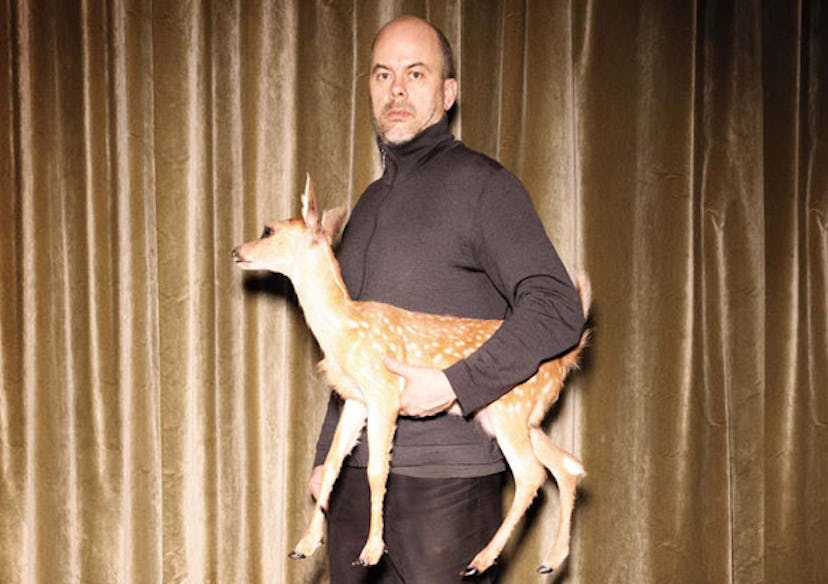

After ringing the bell, one is greeted by an employee and ushered into an obsessively restored landmark building, which in the 19th century functioned as the silver manufacturing headquarters of Tiffany & Co. On elegant display is the work of decorative artists and artisans curated by the company’s 48-year-old owner and founder, Rhett Butler. (Though his first name is Edward, his parents called him Rhett. “I’m sure there was a sense of humor involved,” he says today.) Butler’s current inventory includes hand-turned candlesticks by Ted Muehling; gold, iron, and steel bracelets, earrings, and pendants from Philip Crangi; and one-of-a-kind pieces by the German-born jeweler John Iversen.

Hidden in plain sight in a series of bronze-and-glass display cabinets, however, are the objects of Butler’s true vocation: scores and scores of knobs and pulls made variously of steel, silver, brass, bronze, dendritic agate, coral, ebony, amethyst, mother-of-pearl, porcelain, jade, amber, and mercury glass. Butler is the proprietor of the world’s largest collection of fine architectural hardware—countless doorknobs and knockers and cabinet pulls, along with gilded hinges, hand-chased bronze finials, thumb latches, strap hinges, and their every conceivable variant. And if such a thing simply doesn’t exist in his more than 30,000 catalogs, designs, blueprints, molds, and finished objects dating from the 1600s, he’ll make it for you. If you desire, say, a bespoke hand-patinated solid bronze ladder for your library ($800,000) or a historically accurate renovation of a $400 million Virginia horse farm—in short, if you’ve graduated from Restoration Hardware to the big leagues—Butler’s your man, though he’ll also happily refit a simple, smallish apartment. Butler’s friend Sofia Coppola has leaned on the hardware maestro for inspiration and assistance on several films. (The flurry of faxes about a home renovation sent to Bill Murray by his wife in Lost in Translation were on E.R. Butler letterhead, and included Butler’s renderings.) More recently, he’s consulted on Roman Polanski’s next film, God of Carnage, currently filming in Paris.

A few minutes later, Butler emerges from his offices in the back of the building. I ask him about a collection of decorative bronze rectangles arrayed atop a display case. Are they paperweights? A puzzle? Raw ingredients for a modular, ornamental trivet? “All of those things,” Butler says before filling me in on their intended use as a box chain for a chandelier that conceals the hanging cord inside itself. He designed it after noting that most chandelier chains are “inferior to what they could or should be,” as he puts it. “There’s such a dearth in the market of anything other than a series of oval links that I just started playing around.” Although Butler has the history of an industry on his shoulders, play seems to be his modus operandi.

From top: Butler’s inventory of vintage and contemporary doorknobs; Deborah Ehrlich–designed lighting for Blue Hill at Stone Barns.

“You ready?” he asks, and we head outside and around the corner, where we hop in his BMW for a 15-minute drive, across the Manhattan Bridge to the Brooklyn waterfront. Here lies the heart and soul of his operation: a 130,000-square-foot circa 1887 former foundry that is part nuts-and-bolts factory, part archives and inventory, and part home (he lives in an adjoining carriage house). As it turns out, trying to understand Butler’s vision without seeing his Red Hook Works is like trying to understand Jay Gatsby without knowing about the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock—or trying to plumb the soul of Willy Wonka without visiting his Chocolate Factory.

The Works began, like most things central to Butler, as a kind of dream. “For years I had a very specific fantasy about finding a compound on or near the water with a smokestack and a pinwheel layout, with a courtyard and a factory,” he says. At the time Butler’s manufacturing operation on Spring Street was proving untenable, so starting in 1996 he spent two solid years doing little else but driving around looking at real estate.

When he first saw the huge redbrick compound we’ve just pulled up to, it was covered in additions and fencing, and was being used in part as a storage facility for large-scale garbage containers. “Once I got inside and started walking around, though”—one floor was filled with scores of people working out of tiny cubicles; a hospital occupied another section—“I realized the place had really great bones.” He has since torn down four structures and stripped everything to its original state, along the way crafting a garden and a reflecting pool out of what was once a work yard. As if to commemorate the achievement—which, in keeping with the Butler ethos, is still very much a work in progress—the compound’s smokestack has been affixed with a large gilded B on the side facing the water.

Walking through the large central building, we pass a number of idiosyncratically furnished semiprivate alcoves, home to artisans, designers, archivists, and finishing artists. (Butler, who started out working for his father’s architecture restoration business, now employs about 60 people and has projects in a dozen countries.) Row after row of floor-to-ceiling shelves dominate the space and contain hundreds, if not thousands, of identical gray boxes with labels reading key escutcheon and crystal shell shanks and olive knuckle trim rings. Near an enormous pagoda chandelier made by the Viennese glassmaking masters J. & L. Lobmeyr (the piece was used to show off Butler’s box chain in the Prince Street vitrines) is a room filled with plans and research and molds for his restoration of the historic Tweed Courthouse in downtown Manhattan. “All the hardware had been stripped,” Butler says. “They had nothing. And then they found two small pieces of metalwork—an escutcheon plate and a key escutcheon—on a door sealed inside a massive wall. We had to extrapolate all the information from that.”

Our walk-through continues past giant scales salvaged from the Denver Mint; a carved easel that interested Butler only for the metal medallion placed at its center by another long-defunct company; a plain-looking wooden screen, which upon closer examination reveals a rare hinge that he is, after five years of research, on the verge of reinventing for modern use; prototypes for a lighting series designed by Deborah Ehrlich for Blue Hill at Stone Barns that Butler is manufacturing; and a small room filled with taxidermied birds and animals (“I bought the collection from the daughter of the chief of the Mohegan Indian tribe,” he says). The building next door houses a half-million-dollar Japanese laser-cutting machine and another contraption capable of focusing water jets the width of a human hair at pressures high enough to cut through six inches of solid steel. The mind, frankly, starts to reel: Is Butler a hardware salesman, an entrepreneur, or a latter-day Wonka, spinning gold from a trove of eccentric obsessions?

“I’m very influenced by the confluence of art and science and the idea of the kunstkammer,” Butler says, using the German word that translates as “theater of the world” or “memory theater.” Butler prefers “cabinet of curiosities,” and expands the concept to describe his motivating philosophy. “There was a certain age when man was more interested in understanding the world around him—exploring foreign lands, discovering and cataloging different materials and metals and life forms,” he says, gathering steam. “People were literally blowing, in glass, sea creatures and botanicals and microbes and things you could only see under a microscope, so these beautiful things wouldn’t just wither and die.” When he isn’t busy creating them himself, Butler makes a point of seeking out current-day kunstkammers of all sorts—“rooms of scientific instruments, microscopes, telescopes, taxidermied animals, cameos, medallions, coins—anything people would collect to demonstrate natural wonders. It’s a great motivator,” he says.

Back among the stacks, the labels on the gray bins have veered away from describing bolts and hinges and levers, and now read medical-grade silicon rubber and vaginal jewelry and mechanical vibrators—raw material and research, it turns out, for Butler’s design and production of “instruments of pleasure” for boudoir-couture specialist Kiki de Montparnasse.

The research has taken Butler back to old medical texts that prescribe self-stimulation as a clinical cure for neuroses and to eBay for early examples of sex toys. He has traveled to the Netherlands, to the only manufacturer capable of making monofilament strong enough for his black onyx–detailed restraining cords. These days, though, he is experimenting with the design of a tubular stainless steel mechanism as the linchpin to an entire restraining system. “If it doesn’t work for them,” says Butler, “we’ll sell it to the U.S. prison system.” I laugh. He waits a beat and looks me square in the eye. “I’m not kidding.”

As Butler and I exit the building in the shade of its smokestack and get in his car for the drive back to Prince Street, he tells me about a recent REM experience (“I do a lot of problem solving in my dreams,” he says). This particular dream was so vivid it caused him to wake up and sketch out—he keeps a pad and pencil next to his bed—an elaborate collaboration involving Andrew Zega and Bernd Dams, Paris-based architectural watercolorists who pursue on paper what Butler realizes in brass, metal, bronze, and glass. Zega and Dams had just completed a monumental project, rendering Chinese-inspired garden pavilions around the world in watercolor, and Butler envisioned a very specific partnership: “The next day I e-mailed them: ‘Had a dream. You design chinoiserie-inspired birdcages. I make them to the level of Fabergé. What do you think?’ And they wrote back: ‘We’re in.’”

The plan is to make one birdcage a year for the next 12 years, culminating in a book and a museum show. “It’s total fantasy—rock-crystal columns, everything gilded and interlocked like a puzzle, all materials precious or semiprecious,” he says. “It’s like nothing that’s been done since Louis XV.” The first cage was used last summer as part of an LVMH-sponsored arts program, The Art of Craftsmanship Revisited, on Governors Island, just across the water from the Red Hook Works. (Butler then donated the cage to the Institute of Classical Architecture & Classical America for a benefit auction, where it’s expected to fetch somewhere north of $75,000.)

“The birdcage is a story of making absolutely wonderful but useless items,” says the man whose business rests on absolutely wonderful and useful items. Butler then insists on showing me the second cage in the series, for which he has just finished detailed renderings. It will be held together by exactly one screw, and seems to be either his own personal Rosebud or his Everlasting Gobstopper. “The project is completely esoteric to our business—and at the same time I think it encompasses everything we do,” he says, now back at Prince Street among the strap hinges and knockers and knobs. “It’s literally a kind of insanity project.”