Retro Action

The man had a serious stutter but was saying something about selling clothes that once belonged to his friend’s famous father. Mark Haddawy, co-owner of Resurrection, didn’t ask questions and simply offered the stutterer about $4,000 for the leather getups, most of them fringed, studded and slashed in one way or another. “A few days later, a friend came by who’s really into music and looked at them and said, ‘Where did you get all of Sly Stone’s clothes?’” Haddawy says, recalling the 2001 encounter, adding that soon after, he found six silver bullets in one piece’s pocket. Turns out, another item—an embellished, bat-sleeve motorcycle jacket—had a starring role on the cover of Fresh, Sly and the Family Stone’s 1973 album, on which a toothy Stone is dressed in the number and doing a rock kick, his chest bare and his afro sky-high.

Those garments, which were custom made for Stone by an obscure Bay Area leather designer, will be up for auction October 30 at Christie’s in London along with about 250 other pieces from the private collection of Haddawy and Katy Rodriguez. They opened their first vintage boutique, Resurrection, 12 years ago in a former mortuary in New York’s East Village but quickly began amassing goods that were simply too special to sell. “I love the energy of the stuff,” says Rodriguez. “It represents youth and possibility. A lot of the designers were really at the pinnacle of their careers.”

While one could argue that, given the sluggish economy, now is not the best time to cash in at auction, the duo begs to differ. “Great material is still at a premium, and I just think there are enough people who are still willing to participate,” notes Haddawy, who indeed knows a thing or two about the gavel: In 2006 the Chicago-based Wright auction house sold off his Los Angeles home, the famed Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House No. 21, for $3,185,600.

As for the Christie’s auction, its lots feature majors such as Pierre Cardin, Paco Rabanne, Vivienne Westwood, Yves Saint Laurent and Norma Kamali. A 40-look preview will be held in New York from September 2 to 4. Simon Andrews, Christie’s specialist of 20th-century decorative art and design, breaks the sale into four categories: avant-garde Pop (Sixties); romanticism rebirth (early Seventies); discord and disorder of punk (mid- to late Seventies); and designer wear (Eighties and Nineties). “These are garments that represent the synthesis of fashion and design,” says Andrews, noting that the auction is Christie’s first single-owner vintage clothing sale; its total estimate is about $600,000. “It’s interesting what the clothing says about society as much as what it says about fashion.”

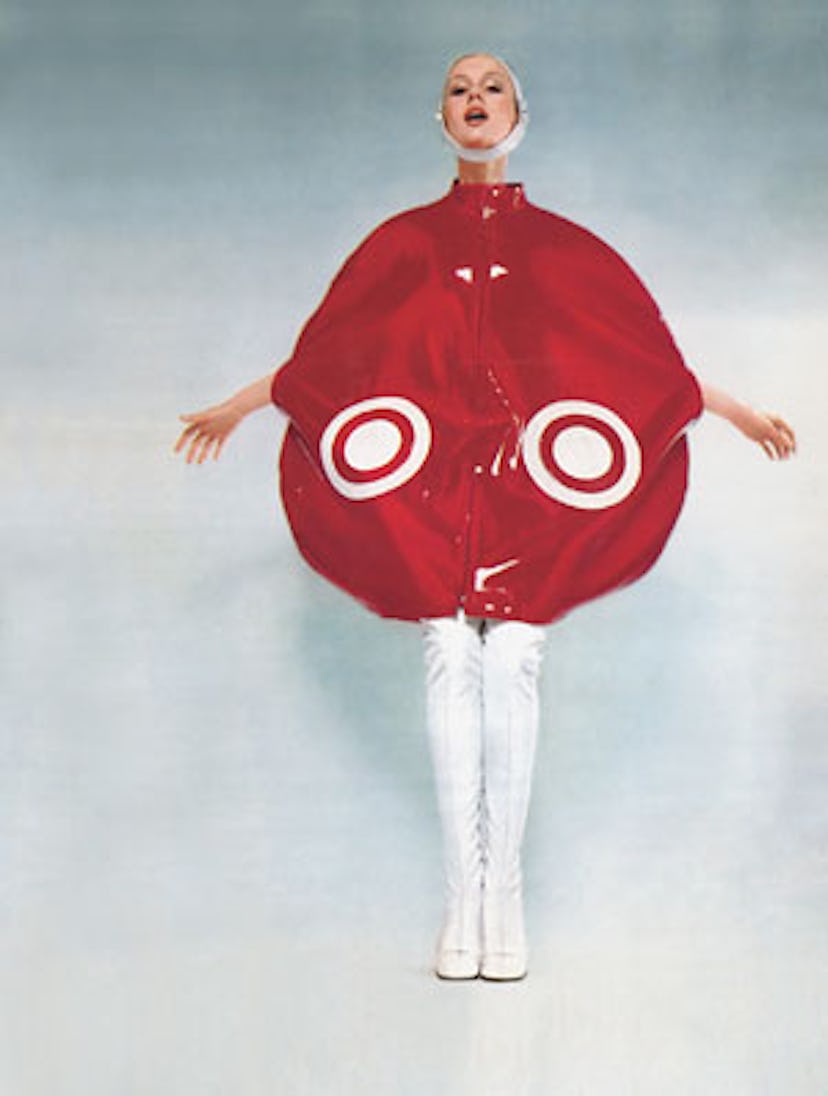

Indeed, Pierre Cardin’s Satellite bubble cape, circa 1969, fuses ideas of Pop art and futurism into one jumbo slice of crimson vinyl. Or take Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s Sex and Seditionaries T-shirts (1975–78). Emblazoned with images such as Union Jacks and upside-down crucifixes, or phrases like god save the queen and destroy, the layered muslin tops were made famous by the Sex Pistols. Such iconography, much of which was created around Westwood’s kitchen table with her artist friends, came to symbolize the anarchic ethos of the decade. “The pieces have a lot of soul. They’re so lived in, and there’s such depth,” remarks Haddawy. “That clothing is truly from the street.”

Growing up in San Francisco in the Seventies and Eighties, Rodriguez was obsessed with fashion. She plastered her walls with magazine pages and idolized her neighbor—a cool “female Mick Jagger” type who worked for Fiorucci—from afar. After studying fine art photography at San Francisco State University, she hightailed it to New York, where she briefly worked at a “s—ty clothing store” on the Upper West Side. She knew she was ready to do her own thing and invited Haddawy, her ex-boyfriend, to join her. “Vintage felt accessible. I wanted to do something fun and have cool clothes and didn’t want to have a boss,” recalls Rodriguez, who now designs her two-year-old ready-to-wear line in a studio upstairs from the Los Angeles outpost of Resurrection. (That store opened on Melrose Avenue in 2000, two years after the one on New York’s Mott Street. The pair closed the original East Village shop in 2001.)

For Haddawy, who then was dealing in pre-Columbian art in Berkeley, fashion wasn’t exactly on his radar, but he jumped at the chance for change. “We didn’t think that much about it; we were naive enough to do it, and being a little naive was better than not,” says Haddawy, who, in addition to running Resurrection, moonlights as an architectural consultant. “I obviously needed to learn about clothing from that moment forward.” Rodriguez schooled him by circling items in magazines and scribbling atop, “Buy stuff like this!” or “Don’t buy stuff like this!” Before he moved to New York, she mailed the inspirations to him in California. “Sometimes he would send me back photos of stuff he was buying. I can still see those pictures now: hideous, matronly Fifties party dresses,” Rodriguez recalls with a laugh. “But he learned very, very quickly.”

Case in point: Haddawy soon found himself bidding on Pierre Cardin’s nickel-plate cuff necklace (1969) against none other than the designer himself, who wanted it back for his archives. Haddawy won the piece, albeit at a hefty $8,000 price. “That was a lot of money for us, but it was incredible. There are probably two of them in the world,” he says of the bauble, which hangs from neck to abdomen, with large clear bulbs at each end.

Yet at this particular auction, the Paco Rabanne garments are expected to fetch the highest bids. There’s a cutout aluminum frock (1966), which looks more armorial than sartorial, and a leather and metal biker jacket the designer made for Brigitte Bardot in 1967. Still, Patricia Frost, Christie’s specialist of textiles and couture, predicts that Rabanne’s wedding gown, made from slivers of white leather held together with only metal rings, will take top billing; its presale estimate is about $15,000. “His design is diametrically opposed to the normal idea of a wedding dress,” Frost says of the garment, which was commissioned in Paris in 1967. “It says that the bride is a strong, independent person, wearing what looks like chain-mail armor. She is going into battle and is no shrinking violet.” It comes as little surprise, then, that the wedding was called off. The bride’s sister held onto the dress for decades but finally sold it to Rodriguez and Haddawy in 1999.

While Frost is a huge fan of the Rabanne lots, she also is quick to rave about those by Rudi Gernreich, an innovative designer whose quartet of modernist jersey gowns (1975) features sculptural attachments, designed and signed by jeweler Christopher Den Blaker, which wrap the neck, shoulders or arms. “It’s not a mass production thing,” adds Frost. “It’s really wearable art.”

In the end, such is Rodriguez’s hope for the collection: that the clothes are bought to be worn. “That was always one of the messages behind Resurrection. It was never supposed to be this ultra-rarefied thing,” says Rodriguez, who, prior to the sale, often donned much of the garb. “That’s what’s been so cool…. There’s been this tremendous energy because people wear the clothes. And that’s what they’re designed for, you know?”

courtesy of Vendome Press