The 4th Prospect New Orleans Triennial Is Full of Black Art, But Does It Make Enough Noise?

For some time now, identity has been the driving force of contemporary art, which has felt the heat of America’s blood boiling for years before Donald Trump’s election sharpened the edges of those feelings, gave them a foil, and drew the bitter lines. But New Orleans, where the fourth Prospect triennial opened this past week, is a more blurry place. It’s at once the most African, most European, and probably most Caribbean city in the U.S. And the mix isn’t smooth like a roux—it’s more a jambalaya. Things are complicated there.

On the one hand, there are the sunny lifestyle reports on the rapidly gentrifying parts of the city, on the other there is the dark forecast for neighborhoods that still haven’t fully recovered from Hurricane Katrina, more than 10 years later; on the one hand, there is the pleasing scent of the city’s reputation as a Creole-flavored melting pot, on the other there is the bitter after taste of the white supremacist protests, and the counter-protests, following the removal of four Confederate statues in New Orleans just this year.

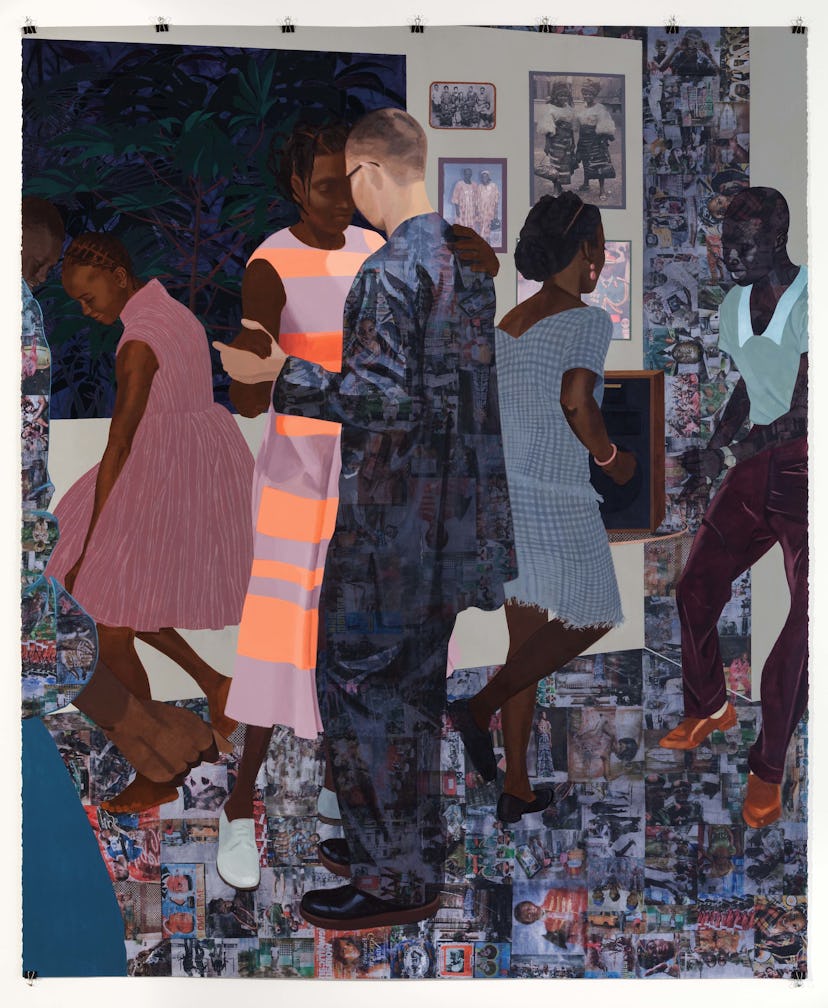

Artists who make art in the first person—in both the “I” and “we” forms—seem to have also arrived at a crossroads of public image these days: either the art is seen as an act of protest or it is seen as an act of celebration of self. With some notable exceptions, the most visible artists at Prospect.4—titled “The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp” and put together by Trevor Schoonmaker, an established curator from the Nasher Museum at Duke University—have opted for the latter.

Derrick Adams in Louis Armstrong Park.

“Everything I do is about that,” said Derrick Adams, who has revived interest in black artists like the cult fashion designer Patrick Kelly by featuring them in his own work. “As an artist, you have the ability to talk about so many things. For me, I don’t want to acknowledge direct relationships to oppressive structures—I know other artists are already dealing with that. I want to make people aware of brilliant things that exist in American culture that aren’t talked about, and to bring light to it in a way that enhances its discovery.”

We were sitting in Louis Armstrong Park near the French Quarter, where Adam was showing a video work featuring his own discovery: a duo of street dancers, cousins Torrance and Derrick Jenkins, who with youthful ingenuity had nailed crushed soda cans to the bottom of their Air Force 1s to reinvigorate one of the oldest black arts, tap dancing. Adams happened upon the kids by chance two years ago while visiting New Orleans for a friend’s birthday—and then had to work hard to find them again for his Prospect commission. “They didn’t have phones even,” he said.

Eventually, after driving around the Quarter for hours, he located the Jenkins cousins, and paid them handsomely to film what was by definition public domain. “I was paying them to do this street performance, but other people were walking by us, just filming it on their phone and posting it,” Adams recalled. “And I’m laughing. But I wanted them to know I was investing the time and money to do this presentation of the piece so that people who see it in New Orleans will have a totally different appreciation for this art form, whereas they may have overlooked it as a tourist attraction.”

Watching Adams’s *Saints March*, 2017.

The video, Saints March (2017), is an attractive formal rendering of a happenstance art, with a slow and mournful a cappella version of Louis Armstrong’s “The Saints Go Marching In” soundtracking the tapping sneakers. Originally, the video was meant to be projected inside street trolleys, but there were technical difficulties—probably for the best, Adams suggested, since the noise and crowds in a trolley would’ve drowned out the contemplative work.

That raises one of the central questions of every Prospect: How to make public art stand out in the streets of a city already overflowing with it?

Out in Algiers Point, visible across the Mississippi River from the French Quarter and reachable by a 10-minute ferry, there were some answers. Historically, it’s known as the site where African slaves first landed in New Orleans, before being taken and sold in the Quarter. The firebrand artist Kara Walker, last seen presenting the severed head of Donald Trump to New Yorkers, was commissioned to create a riverboat calliope—a pipe organ like those on old steamboats—along with the MacArthur-winning jazz pianist Jason Moran. The work was ambitious, a little too much so—it wasn’t ready for the opening of Prospect.4, but likely will be for its closing ceremonies in 2018, which happens to be New Orleans’ 300th birthday. Walker, however, did give a preview of it last week on her Instagram. Still a work in progress, it looks to be, like the best of her work, both spectacular as a visual and devastating as commentary.

Less cutting but also eye-pleasing is the work of the artist Odili Donald Odita, a Philadelphian by way of Nigeria. For Prospect, he adapted his identity-based abstract installations—the colorful fields and geometric shapes of his wall murals are metaphors for the different people who come together in one place—to places like the ferry at Algiers Point, one of the 14 sites across the city where his brightly-hued flags fly high. Though the ferry flag tells the narrative of slavery at Algiers, it is not a starter of conflict—it’s too well-designed and well-balanced for that—but an argument for the open and heterogenous mixing of colors and histories.

As Odita and I chatted at the dock by the French Quarter, our conversation was constantly interrupted by the bleating of the ferry horn. There was a lot going on, in general, on the boardwalk, and I feared that his flags might get swallowed up by the noise of the city. To the public eye, these weren’t conversation starters, exactly—they didn’t scream, as Marilyn Minter’s do, “Resist.” It made me almost hope for a little controversy. In fact, yes, I wanted there to be something to talk about. (Maybe I wanted the Kara Walker.)

Odili Odita’s flag on the Algiers Point ferry.

Despite being in a city where there is so much public art, or because of it, Prospect.4 feels a little unsure out in the open (save for the blistering plein air guitar performance created by the artist Naama Tsabar and put on by a group of 21, most of them women, in Washington Square Park). This triennial is still very much for its core art world audience. One of my favorite Prospect discoveries is the rising star Genevieve Gaignard, a kind of mixed-race Cindy Sherman who re-designed two rooms into a combination salon and chapel, with old furniture, church pews, found photos, mirrors, and wallpaper that works in the schematics of slave ships. The installation was located in the lobby of the Ace Hotel, where many of the artists were staying, not to mention guests of Serena Williams’s wedding, which took place in New Orleans at the same time. Gaignard’s made-over room and her inventive self-portraits were vibrant and fresh and felt right in their place. It was something that people were talking about—and not just because Beyoncé was spotted admiring it.

Genevieve Gaignard at her installation in the Ace Hotel.

Related: The Obamas and the Inauguration of Black Painting’s New Golden Age In America