In Bong Joon Ho’s World of Domestic Bliss, Cho Yeo Jeong Is the Star

A conversation with the Parasite director about Alfred Hitchcock and the famed house in his latest film—plus, a behind-the-scenes look at the photo shoot he led.

In his film Parasite, the director Bong Joon Ho depicts the parallel universes of two families of four—one rich, one poor—who infiltrate each other’s lives. When the son of the impoverished family is employed to tutor the young daughter of the affluent one, he senses an opportunity, and in short order his sister masquerades as an art therapist for the well-off family’s withdrawn son; his father becomes the family’s chauffeur; and his mother displaces a beloved housekeeper. From their flood-prone semibasement apartment in a slum, the Kims ascend to the Parks’ sleek mansion on a hill.

The movie deftly seesaws between empathy for one side and the other: The tonal shifts in Parasite happen so subtly that victims become aggressors—and vice versa—with fascinating speed. Director Bong, as he is known in South Korea, his native country, creates a lacerating, highly entertaining commentary on class resentment and envy. “Parasite is a comedy without clowns, a tragedy without villains,” Bong has said. It’s a film in which the moral high ground does not hold.

Cho Yeo Jeong wears a Celine by Hedi Slimane jumpsuit, sunglasses, belt, and boots.

Parasite-mania began in May at the Cannes Film Festival: Check out #bonghive for posts by a devoted group of followers of the director’s films, including The Host, a monster romp; Snowpiercer, a futuristic epic of class warfare on a train; and Okja, about a girl and her giant, genetically modified pig. At Cannes, Parasite won the top prize, the Palme d’Or, which cinephile fans rechristened the “Bong d’Or.” Since then, Parasite has grossed more than $150 million worldwide and received six Oscar nominations, including for Best Picture—a rare achievement for a foreign-language film, and a first for Korean cinema.

Louis Vuitton dress; Bulgari earrings; Tiffany & Co. necklace; the Row sandals.

After Parasite’s first screening at Cannes, the audience’s enthusiastic reaction surprised Bong. “It is a great joy when people give you a standing ovation,” he told me through his translator, Sharon Choi. “But it is also very complicated. They put a camera on you and they want you to speak. At that moment, I saw that Parasite was having a different impact than my other films. I was happy. But I was also hungry. I looked at my cast and said, ‘Let’s go and have dinner.’ ”

Prada dress; Tiffany & Co. necklace; Vex Clothing gloves.

Bong smiled. He and I were in a restaurant at the Four Seasons Hotel in Los Angeles, just moments after Parasite had been honored at a lunch held by the American Film Institute. Brad Pitt had made his way to Bong’s table. “My cast took photos with Brad Pitt!” he reported. “And also Jamie Lee Curtis!” Bong, who is 50, was dressed all in black: black suit, black shirt, black tie. He is tall, with a mop of unruly hair and a handsome, boyish face that seems to always have an air of bemusement. He has a big laugh, but says he is haunted by the complex anxieties of the world: climate change, income disparity, social decline. “I can’t cry every day, so I make films,” he said. “And humor comes from my fears, also. We are all trying to find our way.”

Loewe dress.

Initially, Bong studied sociology at Yonsei University, in Seoul, but in 1992, during his junior year of college, he started making short films. From the very beginning he was meticulous about his work, carefully storyboarding every shot, just like Alfred Hitchcock had. “I love Hitchcock,” Bong said. “Before making Parasite I watched Psycho many, many times.” It’s no coincidence that in Parasite, like in Psycho, a long staircase leads up to a house filled with secrets. But although many eager fans have searched for the modernist masterpiece in Bong’s film, it was actually a set. “In the movie we show a photo of a well-known Korean architect who has rich, young clients, but that architect did not design it,” Bong says, laughing at his in-joke. “And now people in Korea are trying to buy the Parasite house.”

Loewe dress.

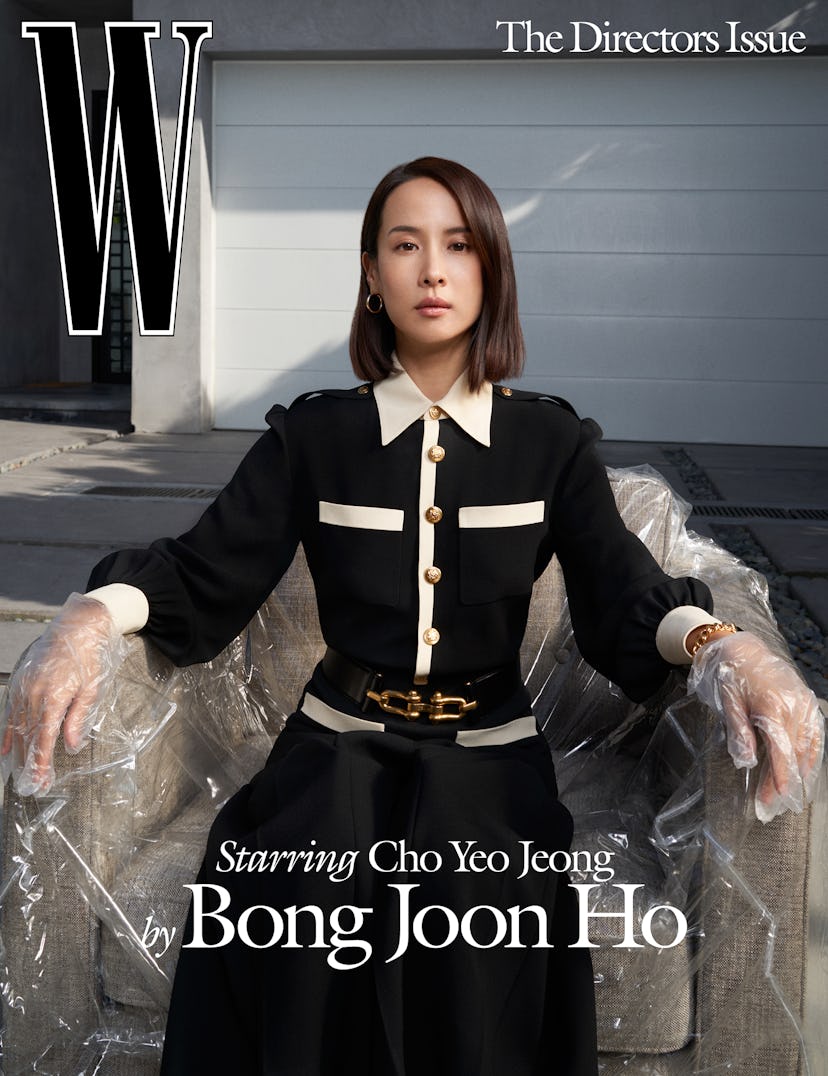

When W asked Bong to create a photo portfolio, he wanted to find an actual house that was very similar to the one in the film. “I would like to create a kind of sequel to Parasite,” Bong explained. His plan was to focus on the wealthy matriarch of the Park family, the naive young mother, played by Cho Yeo Jeong, who won the South Korean equivalent of the Academy Award for Best Actress for her work in Parasite. “The rich mother dreams of a world that is bright and very fresh,” Bong explained. “But she’s actually trapped in this glass box that she’s made for herself. She’s obsessed with her young son, but she never hugs him. There’s no physical intimacy between them, regardless of how much she adores him. That tension and fear was what I wanted to show in the movie, and now, even further, in these pictures.”

The Row jacket and skirt.

Bong took out his iPad and scrolled through some inspiration images for the W shoot, which was to be held the next day. “I like this very much,” he said. It was a still from his film Mother, which was made in 2009 and which many critics believe to be Bong’s masterpiece. It is about a woman who must fight for and protect her mentally challenged son when he is accused of murdering a schoolgirl. Mother delves into complex emotions, but, as in Parasite, there is also exuberance and humor. In the photo Bong showed me, the mother’s face was obscured by thick glass. “Do you notice the tiny drops of water on the front?” he asked, while gently waving his hand across the iPad. Bong paused, as if contemplating not only what the viewer would see but also what the subject might be observing from behind the thick pane. “I’d like to try and capture something like this.” He then asked if he could see my bracelet, which had alternating translucent aquamarine and citrine stones. He put the blue gem up to his eye. “The world looks very beautiful through this color,” he said. He tried the yellow citrine. “Not so good,” he said. “Maybe we’ll think about blue.”

Maison Margiela coat, headpiece, belt, and key ring; Vex Clothing gloves; the Row sandals.

The next day, a bright but chilly Saturday, Bong was speaking to Cho in rapid Korean. She was standing in a narrow alley on the side of a modernist house in Hollywood, wearing a white Louis Vuitton dress. As Bong spoke, Cho made tiny adjustments to her posture—a hand held closer to the face, a finger arched just so. “I want to focus on the idea of touch, of contact,” he explained. “She has a fear of being contaminated by the world. Her house is so clean, but she is afraid of being invaded in some way.” As always, Bong tackled this terror of the unknown with an unexpected twist. He imagined his heroine wearing high fashion and thick kitchen gloves, scrubbing her already spotless floor.

Giorgio Armani tuxedo; Vex Clothing mask; Tiffany & Co. necklace.

“I want to make everything complicated,” he said, as he walked around the house. He motioned to the photographer, Lee Jae Hyuk, who is also South Korean and worked with Bong on the poster for Parasite—a seemingly conventional portrait of both families (the Kim clan is barefoot), except that in a corner there is a mysterious pair of legs. “In the film, the people with smaller eyes are the ones tricking the people with bigger eyes,” Bong said, as he gestured toward Cho. “The rich wife has large doe eyes—very expressive.” He laughed again. “Before Parasite, she usually did roles with more sex appeal. Now, suddenly, she’s in a series of coffee ads in South Korea, playing her character in Parasite!”

The Row jacket, skirt, and sandals.

Bong took out his iPad again. “What if we did this picture?” he asked Lee. (It must be noted that everyone in Bong’s orbit calls him Director Bong—and the same goes for Photographer Lee. Even in America, Korean manners hold sway.) It was a photo of Tilda Swinton in –Snowpiercer. She was sporting giant false teeth, enormous glasses, and a fright wig. There was a filthy sneaker balanced on her head. “I want something dirty next to her face!” Bong exclaimed. “Something that she can’t possibly erase by cleaning.”

Dolce & Gabbana jacket, bodysuit, and skirt; Maison Margiela headpiece; Vex Clothing red gloves; stylist’s own apron.Directed by Bong Joon Ho; Photographed by Lee Jae Hyuk; Styled by Sara Moonves.Hair by Bryce Scarlett for Moroccanoil at the Wall Group; makeup by Emi Kaneko for Chanel at Bryant Artists; Manicure by Michelle Saunders. Set design by Gille Mills at the Magnet Agency. Produced by Wes Olson at Connect the Dots, Inc.; Production manager: Jane Oh at Connect the Dots, Inc.; Lighting director: Zac Hahn; Photography assistants: Brian Elioff, sash Popovic; Digital technician: Daniel Kim at Milk Studios; Retouching: D Touch Creative; Fashion Assistants: Allia Alliata di Montereale, Nadia Beeman, Julia McClatchy; Production Assistants: Nikki Patrlja, Jeremy Sinclair, Zack Higginbottom; Hair Assistant: Michelangelo Arevaloe; Makeup Assistant: Misa Kanbe; Manicure Assistant: Pilar Lafargue; Set Assistants: Bucky O’Connell, Doug Stearns, Brian Rothlisberger; Tailor: Hasmik Kourinian at Susie’s Custom Designs.

In Korean, he carefully outlined the character he wanted Cho to play: She is very lonely, but craves personal contact; she is afraid of water, but must use it to clean; she longs to hold her puppy, but can’t feel its fur through her gloves. “In the end, she is braver,” Bong said, sounding hopeful for his character. “We all try. We all want to be brave.”