Like most little girls, Osanna Visconti di Modrone loved playing grown-up, teetering around in her mother’s high heels, smearing on her red lipstick and piling on heaps of her flashy baubles. Yet unlike her young friends, Visconti was plucking Lucio Fontana, Salvador Dalí and Mario Ceroli pieces from the jewelry box of her avant-garde, well-to-do madre.

Today this early introduction to such contemporary artists informs Visconti’s own jewelry line—modern designs with quirky textures—which debuted two years ago and has found fans in Silvia Venturini Fendi, Allegra Hicks, Bianca di Savoia Aosta Arrivabene and Chantal Hochuli, Prince Ernst of Hanover’s ex-wife.

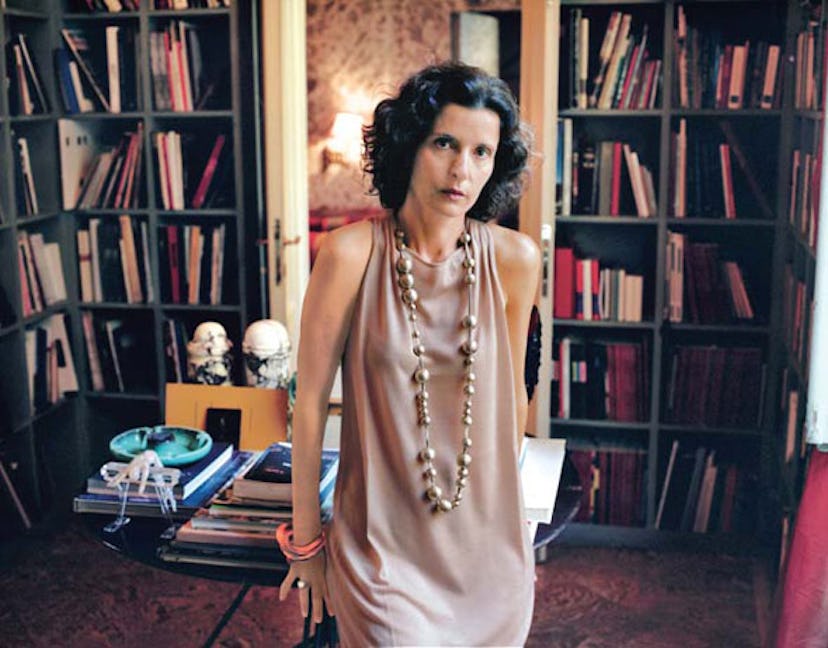

Art also fuels the relationship of the Rome-born Visconti, 45, and her husband, Giangaleazzo Visconti di Modrone, whose noble lineage stretches back to the Middle Ages. In 2000 he opened a contemporary art gallery in Milan, where the couple resides with three of their four children, ages eight to 15, in a sprawling apartment near the Duomo. (The Viscontis’ palazzo is pure classicism, though a flying saucer–like Anish Kapoor sculpture above the fireplace provides a contrast to the frescoed ceilings and striped armchairs.) Progeny permitting, Visconti joins her husband on trips to the Venice Biennale or Art Basel Miami Beach.

While Visconti describes her collection, sold in more than 30 stores worldwide, as conceptual and contemporary, her first priority, she says, is for “women to wear my jewelry and feel good in it.” Over-the-top jewels, she adds, are “unflattering and difficult to wear.” Her pieces, rather, are bold but lightweight and sans a trace of bling. Or as Arrivabene gushes, “They are like small sculptures. I wear them day in and day out because they look just as good with a shirt and jeans as over a black cocktail dress.” (Visconti’s double-strand silver coin necklace is Arrivabene’s current favorite.)

In her studio, a former stable with terracotta floors and paint peeling from the walls, Visconti works with a crop of seasoned artisans who hand-assemble each piece. Besides matte 24-karat gold, which Visconti describes as “extremely ductile,” the designer typically employs silver, in its original color as well as gold-plated, burnished, copperized and bronzed. Once treated, the metal is cut into strips and coiled into rings, or shaped into flat loops, leaves, spirals or coins for necklaces, bracelets and earrings. Save for the occasional raw rock crystals or untreated diamonds, Visconti prefers to stick to metals. “All you need is a slight change in volume or thickness,” she says, “and the piece looks completely different.”

Her affinity for the pure and simple may stem from the 20 years she spent in Rome perfecting her craft under goldsmith Teresa Schwendt, who taught Visconti the traditional cutaway wax technique—fusing metal with a wax mold—that the designer still employs. Prior to her work with Schwendt, Visconti studied costume and jewelry history at Rome’s Accademia della Moda e del Gioiello, later moving to New York, where she interned in Christie’s fine jewelry department. There, Visconti crossed paths with Andy Warhol, who, she recalls, would marvel over the trays full of gems she held out for him, some of which were “sapphires the size of a swimming pool,” she says.

From top: Osanna Visconti di Modrone’s gold-plate and blackened sterling silver bracelets, $2,980 each, at Adam, New York, and 24k gold leaf earrings, $890, at 10 Corso Como, Milan.

Such razzle-dazzle ornaments may not be up her own alley, yet Visconti is a firm believer that jewelry should always be part of a woman’s regimen. “It’s a bit like makeup,” she says. “You wear it to look more beautiful.”