No Country for Old Men

In the Coen brothers’ lethal western No Country for Old Men, Tommy Lee Jones, Javier Bardem and Josh Brolin tell a bleak tale of dust, dread and dire laughter.

The border-land terrain of Cormac McCarthy’s novel No Country for Old Men is an emptiness of raw plains cratered with ancient calderas, where the manmade lines that mark legal boundaries are but lightly scratched in the earth and the contest between good and evil does not have a sure outcome.

In Joel and Ethan Coen’s minutely faithful film adaptation, in theaters in November, the barren landscape glowers with an almost mythological grandeur, less a backdrop than a physical presence to be reckoned with by the film’s macho acting trio of Tommy Lee Jones, Javier Bardem and Josh Brolin. While shooting in the summer of 2006 near the small towns of Marfa, Texas, and Las Vegas, New Mexico, the set was haunted by violent storms that rumble in the film’s background like some cosmic tumult.

“That thunder is real,” says Bardem, who plays hired killer Anton Chigurh, an unstoppable reaper living by his own darkly rational principles. “We’d have 50-miles-per-hour wind come up out of f—ing nowhere,” adds Brolin, whose Llewelyn Moss becomes Chigurh’s target when he stumbles upon a suitcase of drug money and opts to keep it. “We’d have the dust devils come in, or it would rain like a monsoon for 10 minutes and then be gone.”

Jones with costars Josh Brolin and Javier Bardem.

The Coen brothers are known to be exacting and scrupulously efficient on the set, but they hadn’t wanted overcast skies and had scheduled their shoots according to the weather forecast. “The reports were for blue sky,” Brolin says. “Obviously, it didn’t work out. And it ended up being amazing.”

“Amazing,” agrees Bardem.

As they talk, the two actors are sitting at a round table in an otherwise empty Toronto hotel room, smoking cigarettes and tipping the ashes into their empty glasses. It’s the end of a long promotional weekend at the Toronto Film Festival, where No Country had its North American premiere before a rapturous audience a few nights earlier, and the men have evidently enjoyed their time here. Bardem tells a pungent story he asks not be printed out of concern that his agent would “fire” him, while Brolin recounts the fun of a day spent with Sean Penn, Eddie Vedder and Woody Harrelson, who has a small role in No Country as a 10-gallon popinjay murdered by Chigurh.

The pair’s jovial banter makes a surprising contrast to the film, in which their intense performances—a battle between Brolin’s fierce survival instinct and Bardem’s lethal focus—are so seamless as to appear to be typecasting, not acting. The film’s remarkable verisimilitude is even acknowledged by Jones, an eighth-generation Texan whose manner of speech tests the limits of understatement. (And that’s when he chooses to state something at all: Brolin says half jokingly that Jones “doesn’t feel the need to uphold his end of the conversation.”) “I was impressed with Josh Brolin’s use of the language,” Jones says a day earlier in a different hotel’s dining room. “Josh’s character is supposed to be from San Saba, Texas, which is where I was born and where I live. And you could imagine Josh’s character driving around town in his pickup.”

Bardem’s character, Anton Chigurh, is an unstoppable—and possibly inhuman—killer.

It’s a startling breakthrough performance from the 39-year-old Brolin, who, despite his numerous film credits—including fine work in Paul Haggis’s recent In the Valley of Elah, David O. Russel’s Flirting With Disaster and Ridley Scott’s upcoming American Gangster—has not shouldered the dramatic weight of a similarly pivotal role. His Llewelyn Moss is a dusty everyman, a professional welder who lives in a trailer with his sassy young wife, played with a pitch-perfect accent—says Jones—by Scottish actress Kelly McDonald. As the movie begins, Moss has been hunting antelope on the open plains, and it is while tracking the blood spoor of an animal he shot that he happens upon the carnage of a drug deal gone bad and, in a moment of lonely reckoning, makes his fateful decision.

“When I open up the satchel and I find the money, I look up and I go, ‘Uh-huh,’” says Brolin, explaining that he ad-libbed the crucial “speech” after discussing with the directors a range of options for registering the moment. “We actually talked about and rehearsed that one word, and Ethan always laughs when he hears it [in the final cut].”

The Toronto audience also burst out laughing—which surely says something about the proximity of laughter and dread in the cinematic experience. Throughout its taut two hours, No Country percolates with the unspeakably black humor the Coen brothers perfected in Fargo. Jones gets the best lines and makes the most of them, like a Shakespearean actor who creates dire mirth among the slaughter. Now 61, Jones plays Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, in whose jurisdiction the film’s mayhem occurs, and he looks as if he were pried from the same dry ground. Bell’s wit is equally parched. In one scene, he recounts to his deputy a story he’s read in the morning papers, about a couple in California who took in elderly boarders and then murdered them for their Social Security checks. “They’d torture them first,” says Bell, dismayed at such signs of evil in the world. “I don’t know why. Maybe the television was broke.”

“We were looking for the humor, but you can’t put on a clown nose,” says Jones, who majored in English as a Harvard undergraduate and today studies his favorite novelists deeply enough to read the critical literature about them.

At his interview, Jones is dressed for town in a suit and lace-up shoes, but as he grips a tall glass of beer, he looks as if he’d much rather be back home. His massive hands prove it’s no empty boast when he says that he enjoys working on his ranch north of San Antonio, and the one question he answers with pleasure is about his cattle-breeding operation. “We’re constantly trying to refine the conformation of the Brangus cow, a combination of Brahma and Angus,” he explains.

One of the peculiarities of No Country is that neither Brolin nor Bardem shares a moment’s screen time with Jones. The tense chase sequences between the younger two—classic shoot-’em-up stuff—are counterweighted by a quieter character study of Sheriff Bell as he tries to comprehend the lawlessness and struggles with the profound questions of his own soul. As a result, the three spent little time together around the set, and they got together for dinner just once, after their first day on location. They met up for the 30 minutes it took for the portraits that accompany this story, but Jones didn’t participate in an interview with Brolin and Bardem. He insists they got along “just fine” on set—“They’re two very fine actors, and I happen to like actors”—but the younger men make light reference to the phenomenon of “Tommy’s tension,” which describes an atmosphere that dissipates whenever Jones leaves the room.

Be that as it may, Jones at least comes by his rangeland gruff honestly, and one could say that he is the Coens’ guarantee of authenticity. But to say that alone would be to underrate his performance. His stark speech that ends the film, in which Jones faces the camera across a plain breakfast table and simply recounts a dream about his late father, may be the best two and a half minutes of acting onscreen this year.

How many takes did it require?

“One,” drawls Jones.

Was it tough to do?

“Naw,” he says. “I’d been practicin’.”

The 38-year old Bardem, who was nominated for an Academy Award in 2001 for Julian Schnabel’s Before Night Falls and garnered international attention for his sensitive portrayal of a quadriplegic in The Sea Inside, was hardly the most obvious choice to play a relentless killer in the American West. But according to Joel Coen, he was their first and only choice. “The character in the book, while very vivid, is almost not described, and not at all physically,” said Coen the day of the Toronto premiere. “The approach in the novel is almost coy. [McCarthy] intentionally withholds the nature of the character. We knew it had to be someone who would command attention and hold attention in the movie. Javier is somebody you can’t take your eyes off of, in person and onscreen.”

Brolin gives a breakthrough performance as Llewelyn Moss, a dusty everyman hunted by Chigurh.

Chigurh is the most mysterious character in the film, someone who wreaks death at every turn and has an almost supernaturally lethal competence. His otherworldly danger is telegraphed at first glance by a peculiar pageboy hairstyle. (It’s not a wig.)

“It was a pretty good moment when they did a haircut,” recalls Bardem, “because I saw it, and I said, ‘Well, this is very insane.’ Chigurh is someone who is not really comfortable in day-to-day life with basic things.”

“There’s something a little off-camber about him physically,” adds Brolin, elaborating on the thoughts behind Bardem’s sometimes awkward English. “And the haircut represents it so well. It’s a guy who has no concern at all about how he comes across, which is so frightening.” Bardem reports that McCarthy invented the character’s strange name and admits he is not entirely sure whether the novelist intended the killer to be human or a force of fate that “happens,” as he says, to the other characters.

“That’s the worst thing,” says Bardem. “You see that Chigurh is going to happen, and you do want that to happen. But I think the story works so well that you don’t even question for a second if it’s important that the guy is flesh and blood or not.”

The role required Bardem to master two important props that were foreign to him—guns and cars. He found guns easier. “I can drive as long as it’s straight,” he says, laughing at Brolin’s avid agreement. “But just don’t ask me to turn, man.”

As for the guns, Chigurh wields them in every caliber, but his preferred means of dispatch is a bolt gun of the sort used in slaughterhouses. No Country’s extreme bloodshed, on a par with anything from Sam Peckinpah to Quentin Tarantino, may be roused by McCarthy’s philosophical themes, but even so, it could be potentially off-putting to audiences.

“It’s a very violent story from a very violent novel,” acknowledges Joel Coen. “We tried to be true to the intention and nature of the novel.”

Still, despite the onslaught of gruesome deaths and the fast-paced action sequences, Brolin credits the Coens with having made a movie that is “quiet.” Working again with their longtime cinematographer, Roger Deakins, they have created a spare visual environment, he says, that favors a minimalist acting style, with gestures that register only on the periphery. Late in the movie, for instance, Bardem emerges from a house where he had lain in wait to settle a score. The only indication that he has killed again is that he checks the soles of his boots for blood—just a glance observed from across the street.

“The Coens are trusting the audience that they’re going to pick up on that,” says Brolin. “I think a lesser director would have done the close-up of the foot or something. They keep it wide, and Javier doesn’t have to overdo it.”

“Joel and Ethan wanted an observational feeling to that scene,” explains Deakins. “We know each other well, and we spend a lot of time together before the filming. By the time the camera rolls, we are really in sync, and there is little to talk about regarding the work.”

Brolin’s character with the fateful satchel of money in No Country for Old Men.

At the time the three actors received scripts for No Country, Bardem didn’t know the novel, while Brolin had read it previously on Sam Shepard’s recommendation. As for Jones, he had already read McCarthy’s complete oeuvre, considered by many to be the most significant of any living writer. He had even asked Sony Studios if he could direct All the Pretty Horses, only to learn that Billy Bob Thornton already had the job. (The movie, starring Matt Damon, was released in 2000.) Jones immediately suggested filming the early McCarthy novel Child of God, about necrophilia in the hills of East Tennessee, but the studio balked. Sony executives did agree to let Jones adapt McCarthy’s magnum opus, Blood Meridian, for the screen but then couldn’t stomach the violent script he handed in nine months later.

“But there are a lot of violent movies made out of simple prurience,” scoffs Jones. “I don’t know why this one can’t be made. It’s about something—it’s about everything. Since then, Cormac and I have become friends.”

Many a literary scholar would envy the friendship, because McCarthy is a notorious recluse who had granted only two interviews in the past 15 years before appearing on The Oprah Winfrey Show earlier this year to discuss his recent best-seller, The Road. Spending time with “Cormac” grants one of the rarest cultural credentials around, combining the macho appeal of, say, drinking with Hemingway with the intellectual tang of entering the secretive world of Thomas Pynchon. Jones says that he and McCarthy don’t talk about books but that the author does keep him abreast of his research into arcane matters: “He has figured out what makes a curveball curve.” Brolin also came to know the novelist, after he somehow tracked down his number and called to invite him to the No Country set in New Mexico, an hour’s drive from the Santa Fe Institute, the high-powered scientific research center where McCarthy spends time as the only literary figure in residence. “He wasn’t going to come to the set,” reports Brolin. “The Coens didn’t know him, and they hadn’t talked to him. I called him, and he didn’t call back. And finally, I got a little mad on the phone, and he called me back.”

When they spoke, McCarthy accepted Brolin’s invitation and then enjoyed himself enough to ask to return the next day. “He was just one of the sweetest guys I’ve ever met,” says Brolin, who adds that McCarthy professed to being a big fan of the Coens’ movie Miller’s Crossing. “He’s a brilliant, brilliant guy, and very amicable and open.”

According to Brolin, McCarthy has since seen a final print of No Country with friends from the Santa Fe Institute. “Very good movie there,” he told the actor.

How two cerebral New Yorkers like Joel and Ethan Coen could have such a firm grip on the tropes and manners of a hypermasculine world is not an easy question to answer, but they have managed to find yet another way to make the western fresh, perhaps by embodying the frontier virtue of taciturn competence. Brolin teases that there is more talking in the movie—which is not a lot—than there ever was on set. Which naturally suited Jones just fine.

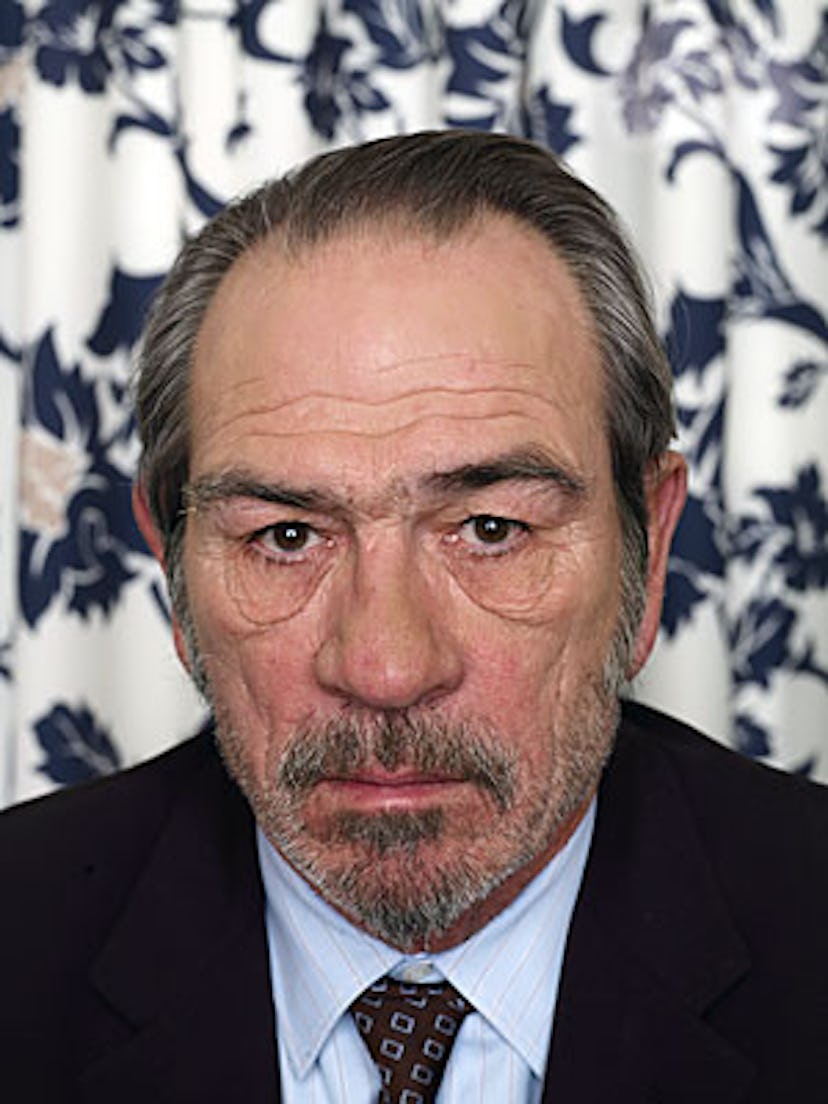

Portrait: Tommy Lee Jones, shot at the Toronto Film Festival, plays Sheriff Ed Tom Bell in the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men.