Nicky Haslam

In his dishy new memoir—and over a lunch interview—the English interior decorator and social titan spills the beans about his celebrated friends and lovers.

It’s a brisk September afternoon in London, but as Nicholas Haslam makes his entrance into the Wolseley, a fashionable café, he is still golden brown, a vestige of his holiday the month before on the Greek island of Corfu. A house party that included cabinet ministers, billionaires, movie stars and aristocrats, his vacation received banner coverage in the British press.

Haslam’s just-published memoir.

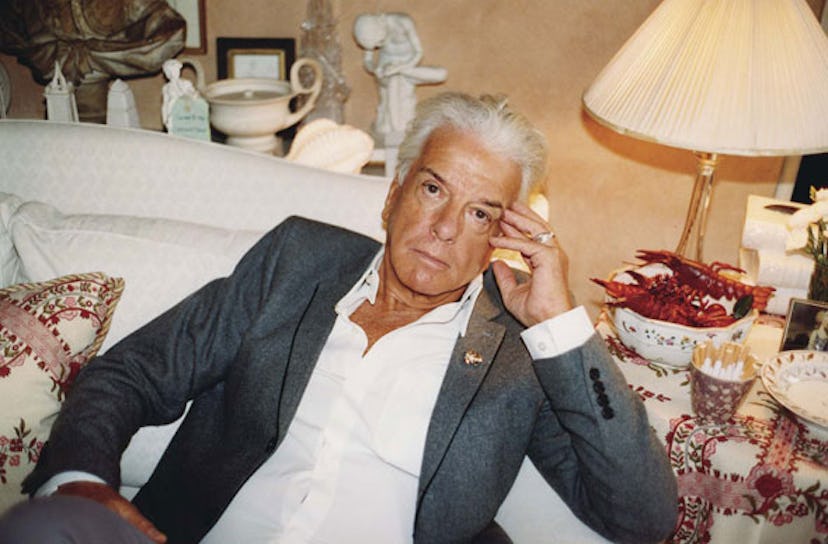

Haslam, a celebrated English interior decorator and bon vivant, is one of those people who always seem to be at the center of the action. This much is obvious after one reads his highly entertaining new memoir, Redeeming Features (Knopf), brimful as it is with tales of his famous friends. The list is endless and stretches from the Duchess of Windsor and Cole Porter to Mick Jagger and Paris Hilton. Thus it seems only fair to open the interview by asking Nicky, which is what everyone calls him, how he feels about being labeled “the star-f—er to end all star- f—ers”—an oft-repeated description first applied to him years ago by his best friend, Min Hogg, the founding editor of The World of Interiors. Haslam—a trim, energetic 70-year-old with a shock of white hair, who is wearing skinny jeans tucked into boots, a loosely constructed gray jacket, and green beads around his neck—becomes slightly indignant. “I’m absolutely not a star-f—er,” he protests. “I could care less if it’s Mick Jagger or the man on the street. I just like interesting people, and I happen to know a lot of stars. But if you want to know the truth, most stars f— me.

“A lot of stars can be ghastly!” he continues. As proof, he cites a recent introduction to “one of the most unpleasant men I’ve ever met in my life. He’s called Sacha Baron Cohen. He was so horrible. I hated him. Wretched mind, with dirty hair and dirty new clothes.”

The encounter took place on Corfu in August, during Haslam’s vacation at the estate of financiers Lord Rothschild and his son, Nat. A media firestorm erupted in the UK when word leaked that the Rothschilds’ guests also included cabinet minister Lord Mandelson, whom some see as the Lord Voldemort of British politics due to his coolly calculated power brokering, as well as billionaire David Geffen, who pulled up on the Rising Sun, the world’s seventh-largest yacht. The Sunday Times of London had all the details on the gathering—thanks, it seems, to Haslam. “We had a very nice evening, the food was delicious,” the decorator told a Times reporter before disclosing that “Peter [Mandelson] was up all night…. He’s always on the phone.” The confluence of political power, big money and upper-class privilege set the press speculating about the deals Mandelson might be hatching, though nothing, in the end, seems to have transpired.

Haslam in New York in the Sixties.

Today Haslam elaborates on the guest list. “Qaddafi’s son was there too,” he says nonchalantly. “He’s called Saif. He’s a big bruiser of a boy, quite good-looking, in a way.”

Haslam proceeds to swoon over Agnelli heir John Elkann, who was also in attendance. “He’s the most adorable boy I ever met in my life,” he says. “Exquisite, unbelievably sweet, the most beautiful clothes and manners. And he adored me, I rather think.”

Growing up in a stately 17th-century manor house in rural Buckinghamshire, where he spent three years immobilized in bed due to polio, Haslam was privileged as a young man but at a far remove from the glitzy milieu he would later inhabit. His father, heir to an industrial fortune, and his aristocratic mother, a granddaughter of the Earl of Bessborough, were Victorians, “but they were very forward-looking,” their son says today.

As a student at Eton, he managed to befriend such luminaries as Cecil Beaton and Lady Diana Cooper. As is demonstrated repeatedly in Redeeming Features, celebrities just come to him, at least by his telling. In 1953, when a then 14-year-old Haslam went on holiday to New York with his mother, he picked up a handsome boy on the subway, who, after a few days’ acquaintance, invited Haslam to spend the weekend in the country with Tallulah Bankhead. (“Of course you must go,” his mother said when he asked permission.)

In the late Fifties he befriended budding photographer David Bailey and supermodel-to-be Jean Shrimpton. One evening, Shrimpton’s sister brought along her housecleaner, “a skinny young lad,” writes Haslam in his book, who wore a tight suit with a T-shirt and exuded magnetism. “‘What’s his name?’ we whispered,” Haslam recounts. “‘Mick,’ she said. ‘Funny surname—Jagger.’” The future rock star became one of Haslam’s closest friends.

Within a fortnight of his second visit to New York, in 1962, Haslam had moved in with Philip Johnson (“who appeared to find me irresistible,” Haslam writes) and landed an interview with Condé Nast editorial czar Alexander Liberman, who gave him a job as assistant art director at Vogue.

In those days the Vogue office housed an astounding cast of characters, ranging from grand aristocrats such as Baron Nicky de Gunzburg to an odd young illustrator named Andy Warhol. The junior staff included copywriter Joan Didion. “She was wonderful-looking, in this waiflike way. She was always coming in in the morning crying, after some disastrous evening. Then during the day she would gradually remake herself and then go out for another evening,” Haslam recalls.

Haslam scored a major coup when he passed along to editor Diana Vreeland a newspaper clipping his father had sent about a fledgling pop group from Liverpool. “They’re too adorable, get them photographed immediately,” she ordered. He’d soon produced the first photo of the Beatles in an American magazine.

With friend Mick Jagger, 2004.

Haslam’s account of Vreeland’s reaction to President Kennedy’s assassination is priceless. After hearing the news on the radio, he writes, he rushed out to tell Vreeland, who was waiting for him at a restaurant. She was momentarily stunned but regained her business sense in a heartbeat: “My God, Lady Bird in the White House! We can’t use her in the magazine.”

“She was ludicrous but wonderful,” he says of Vreeland now.

As Haslam was blossoming creatively, he was hired away by Huntington Hartford, who made him art director of an entertainment magazine called Show. He left a year later, when the mercurial millionaire sold the publication, but during his brief tenure Haslam attracted attention with his smart graphics and innovative ideas, such as hiring a young Diane Arbus to photograph Mae West and getting Barbra Streisand, already a major star, to do a fashion shoot, wearing Rudi Gernreich.

Fortunately, when his job at the magazine ended, Haslam didn’t need employment; he was dating the handsome and rich Jimmy Davison. The pair led a charmed life on a vast ranch they bought in Arizona. When they sailed for Venice in the summer of 1965 on the SS United States, they took with them a stretch Mercedes, a Jaguar, three dachshunds, a Pekingese, mountains of luggage and two manservants.

Their relationship ended at the beginning of the Seventies when Davison dumped Haslam for a hitchhiker. Haslam retreated to Hollywood, where doyenne Jean Howard took him under her wing and he palled around with everyone from Zsa Zsa Gabor to Natalie Wood. In 1972 he returned to England and reinvented himself as a decorator, after his friend Lord Hesketh, impressed by Haslam’s natural good taste, asked him to do up one of his houses. In the decades since, Haslam’s client list has included Ringo Starr, Rod Stewart, Princess Diana and Charles Saatchi. His work, he says, differs from “the rubbish one sees now, which is not decorating, just styling, like piling four trunks up and putting a lime on top.” Haslam prides himself on his individual approach: “I think I have a stamp but not a style. I believe every room speaks, tells you what to do to it. You have to listen to that.”

Although Haslam briefly discusses design in his memoir, the book is heavier on the author’s love life, which has indeed been busy. He records flings with, among others, Jerome Robbins and Bill Blass. He admits today that his motives were not always pure. “His apartment was so beautiful I wanted to be in it,” he says of his one-night stand with Blass. The sex itself was “pretty bad,” he adds. But his accounts of his “very brief romance” in the Fifties with Antony Armstrong-Jones and a lengthier liaison later with Roddy Llewellyn are the real page-turners. The former, of course, married Princess Margaret, and the latter became her lover. The Princess, with whom Haslam was close, suddenly developed a froideur toward him when, he suspects, she was tipped off to his history with Llewellyn. “Oh dear, I thought,” he writes. “Wait till she finds out about my earlier one with Tony.”

Over lunch, the author grows wistful when the conversation turns to his first memories of Lord Snowdon, the title given to Armstrong-Jones after his marriage to the Queen’s sister. “Tony was more fun than anyone in the world, so impish and naughty,” says Haslam, who recently became godfather to one of Snowdon’s grandchildren. “He was heaven on earth.”

In the UK, Redeeming Features kicked up a stir even before its release there on November 5. Haslam’s outing of Snowdon, 79—who he also claims had a premarriage romance with Tom Parr, later a principal in the design firm Colefax and Fowler—has attracted the most buzz.

Rumors of bisexuality have long circled Snowdon, who has fathered five children with two wives and two mistresses, so the revelations were not exactly shocking. But Snowdon initially denied the story. “It’s not true as far as I’m concerned—and I should know,” he told the Daily Mail in mid-September. Two days later, however, the same paper quoted him saying to a friend, “Nicky’s got a book out, and he has got to sell it. I really don’t mind a bit.”

Haslam, for his part, professes not to understand what all the fuss is about. “One did go to bed with people then,” he says. “Lots of people played around. It was a completely normal way of going on. If you thought someone was attractive, there were no boundaries of male or female. The only scandal was sleeping with someone not of your class. That was scandal.”

In the course of his memoir Haslam also bluntly discusses the late David Hicks’s sexuality. Though it was common knowledge in English society that the eminent designer had gay inclinations, he did have a long marriage to the very grand Lady Pamela Mountbatten, with whom he produced three children. But when I make a reference to Hicks being heterosexual, Haslam expresses incredulity: “David not gay? David Hicks was the gayest person who’s ever been!”

This discussion segues into the longtime affair that flamboyantly gay Beaton conducted with Greta Garbo. “Well, the fact that she was Starbo, as well as Garbo, helped,” Haslam surmises. “But I think she was attracted to him, too. And just the other day a woman told me Cecil was very good sex.”

Although Haslam writes amusingly about Beaton’s rivalry with Garbo’s Russian fixer and lover, George Schlee (whom Beaton deliciously put down as a “sinister little road-company Rasputin”), he claims the famously bitchy Beaton wasn’t that nasty. “He was malicious when he needed to be, when the occasion demanded it,” Haslam says as he flags down a waiter to return his steak tartare. “It’s too stringy, a bit gristly,” he notes and orders a glass of champagne instead.

With the lunch rush on, it becomes difficult to keep the interview on track, as Haslam, seated in the first banquette, needs to greet the large proportion of fellow diners he knows, usually with an effusive “Hello, darling!” After each acquaintance passes, Haslam launches into a rundown of their social, professional and romantic statuses.

A reference to the royals leads him to a soliloquy on Princess Diana, whom he describes as his “second cousin twice removed.” After praising her “huge generosity,” he observes she was “sort of schizophrenic.” And he insists her demise was no accident. “I think there was someone who did it,” he says, growing solemn. “I know who it is, but I can’t say.”

It should not come as a surprise that Haslam’s chronic inability to zip his lip has landed him in trouble at times. “Oh God, yes,” says Hogg. “But he has this extraordinary habit of getting forgiven. It’s his charm. When he decides to charm you, there’s not much defense.”

“We’ve all got Nicky stories,” says documentary filmmaker Hannah Rothschild (daughter of Lord Rothschild). “But you have to pardon him whatever he’s done, because he’s such a life enhancer. While you’re with him, it’s like the sun comes out.”

Over the past year, Rothschild had her stamina tested while filming Haslam on his endless rounds of social events for her forthcoming documentary Hi Society: The Wonderful World of Nicky Haslam, which will air on BBC Four in the UK on November 21. “I’m nearly dead from following him around,” she says. “Nicky can’t bear to miss anything.”

“He is often outrageous,” says Picasso biographer John Richardson, a longtime friend. “But he remains hugely popular because he’s a figure of fun. It’s in his nature to want to go everywhere and know everyone.”

As anyone who has known Haslam has observed over the decades, he has constantly transformed his look, kicking off, in the process, several sartorial revolutions. In the early Sixties he practically invented the mod look, with his tight black trousers, leather jackets and pointy boots. Later that decade, inspired by his Southwestern life with Davison, he pioneered denim, becoming, he claims, the first person to be allowed to wear jeans in the Paris Ritz. (It helped, he thinks, that he and Davison were booked in Barbara Hutton’s usual suite.) In the Eighties he wore beautifully tailored bespoke suits from Savile Row.

Then, late in the Nineties—after the breakup of his 11-year relationship with Paolo Moschino, a handsome Italian student he’d met at a bar in London—Haslam gave himself a complete makeover. The results were startling. Pushing 60, he dyed his hair jet black and spiked it with copious gel and clipped rings to his nose and ears. The postpunk, rough-trade wardrobe he adopted featured ripped-to-shreds jeans and leather trousers. The goal, he stated at the time, was to look like Liam Gallagher. “I thought he was so, so…ravishing,” he said in an interview. “I decided I wanted to be just like that.”

A full-on facelift aided the effort. His last memory on the operating table, he recalls in the book, is whispering into his surgeon’s ear, “Do more than we agreed.”

“I wanted to be up-to-date. I didn’t want to be in the past,” Haslam says of that phase. “It’s terribly easy to be well dressed. It’s much more difficult to be badly dressed.” Within the past year or two, he has moved on from punk, let his hair go white and acquired a less radical look, though one still youthful in spirit. “It’s all from Topman!” he says proudly of his ensemble today. “I get it all free!” he adds gleefully, citing his friendship with Topshop owner Sir Philip Green.

Perhaps the latest redo was sparked by Haslam’s 70th birthday, this past September 27. He celebrated the milestone unofficially—and a year early—last October, by throwing a ball that was widely described as the party of the decade. Outside London, in a mansion built by one of his ancestors in 1760, Haslam constructed a set with a revolving dance floor and 12-foot silver trees inspired by the 1946 film Ziegfeld Follies. Since he dislikes birthday parties, he decided to give the fete in someone else’s honor and chose Janet de Botton, a philanthropist who is on everyone’s A-list but seldom socializes. The arrangement, he says, also made it easier to pare down his guest list. “It’s a slightly good excuse to say to someone, ‘If you’re not a friend of X, you can’t come.’ One can’t invite the whole world.”

Haslam ended up asking 900 of his nearest and dearest. The shame felt by those who did not receive a stiffy to the event was humorously expressed by society wag Christopher Simon Sykes in “The Nicky Haslam Calypso,” a song he composed and performed (and later posted on YouTube) as he sat at home on the night of the ball. “Currently across the English nation, there’s only one topic of conversation,” Sykes sang of the bash, which he said brought “great cheer to those who have been invited and misery to those who feel that they have been slighted.”

Among the chosen were Lee Radziwill, Princess Firyal of Jordan, Lucian Freud, Lord Rothschild, Sarah Ferguson, Daphne Guinness, François-Marie Banier, Keanu Reeves, Claus von Bülow and Paris Hilton—who seems to be Haslam’s latest crush. “I adore her,” he says. “She’s very tender and loving.” Of all his guests, he says, she was one of only two (the other being artist Tracey Emin) to send him a handmade thank-you present instead of another costly store-bought item. Hilton’s gift was a collage of photos of the party. “Mostly of her,” Haslam concedes. “But it probably took her five hours, and it came wrapped in a thick box with a big pink bow. I thought that was very touching.”

After almost 70 years of relentless socializing, is there anyone he still longs to meet? “There’s this wonderful lesbian on the radio Saturday mornings, Sandi Toksvig,” he answers. “She’s far funnier than Noël Coward ever was.” And what about his current look? Are there further changes planned? “It’s just for the moment,” he says. “You never know where it’s going to go next.” With Nicky, that’s for sure.

Book: Courtesy of Alfred A. Knopf; Haslam on bed: WWD Archive; all others: Courtesy of the Nicholas Haslam collection