How Michael Bargo Became New York’s Go-To Interior Designer

With his mix of midcentury classics and works by rising talents, Michael Bargo is fast becoming New York’s go-to interior designer.

The New York decorator and design dealer Michael Bargo’s home and gallery space is located on the third floor of a five-story brick building in New York’s Chinatown. Like many tenements on the Bowery, Bargo’s has a storied past (it’s a former flophouse and was the subject of a Depression-era photograph by Berenice Abbott) and a rather unremarkable future (the building shares a block with restaurant supply stores and a karaoke joint). It’s a strange location for someone who traffics in a kind of timeless, blue-chip elegance—Bargo’s primary obsession is French midcentury furniture from the likes of Charlotte Perriand and Jacques Adnet—but the new digs are nothing compared to his previous ones in a mall on East Broadway underneath the Manhattan Bridge, where the floors shook every time a train rumbled overhead. Before that, Bargo was selling out of his former apartment in Brooklyn Heights, a tonier neighborhood that would seem better suited to his high-profile fashion-world clients, who prefer to remain nameless. But Bargo enjoys the contrast his gritty environs provide. “The street is so hectic, you come into this bizarre building with a kind of dingy entryway,” he says, “and then you enter what I hope is perceived as a peaceful, serene, beautiful space.”

Galerie Michael Bargo, as it’s called, is indeed serene—high ceilings, painted white floors, lots of natural materials, and sunshine that streams into the by-appointment gallery in front and the bedroom in the rear, petering out halfway through the moody, lamp-lit living room in the center. A corner, painted black and built out by the artist Luke Todd with bookshelves and a chocolate brown sofa, further divides the space. When Bargo found the 2,000-square-foot rental early last year, it consisted of three small bedrooms and a galley kitchen; Bargo somehow convinced his landlord to defy the conventions of New York real estate and turn it into the open, loftlike aerie it is now.

Bargo, top right, sitting on a Penta chair by Jean-Paul Barray and Kim Moltzer, with his friends and collaborators (from left) Ian Felton, sitting on his Mullunu coffee table; Luke Todd, on a cantilevered raw steel table of his own design; product designer Brett Robinson; Arley Marks of MAMO, with glassware done in collaboration with Jonathan Mosca; and Marisa Competello, founder of Metaflora, beside a custom floral arrangement. The cane daybed and the couch in the background are by Pierre Jeanneret.

When I visited in late summer, the front room was filled with a mix of pieces that would be familiar to anyone who has spent time perusing Bargo’s Instagram account, which he updates with sometimes alarming frequency: a tubular steel Mathieu Matégot lounge chair, a quartet of compass-legged chairs by Pierre Jeanneret, a selection of African figurines, carved wooden stools by the up-and-coming design duo Green River Project, and a settee upholstered in the kind of animal hide Bargo favors for both its neutral palette and its ability to deter pets. (Bargo, who jokingly refers to himself as “the zookeeper,” has two cats, Scotty and Ossie, and Temo, a Chihuahua mix with a broken spine who ably skitters on two front legs and rear wheel supports, but whom Bargo prefers to cuddle in his arms.) “I have a client in L.A. right now, and he always jokes that there’s a ‘Michael Bargo starter kit’—these designers, these colors, these textures,” Bargo says, gesturing around the gallery. “I think this room right now is a good representation of it, especially the colors—or lack thereof.”

The living space features a similar mix of mostly French pieces with a few wild cards thrown in, like a jet black seat by the Finnish designer Yrjö Kukkapuro; a wool ’30s-era Marian Pepler rug; and a Donald Judd–inspired plywood sofa designed by Bargo’s friend Nick Poe. “Everything in the gallery is for sale, whereas back here are items that the cats can destroy, artworks I don’t want to part with, or things that aren’t necessarily provenance but that I just love having,” he explains. Though the living quarters are separated from the gallery by an ocher silk curtain, even Bargo admits that the boundary is porous. “When clients come for an appointment, I’ll have the curtain closed, but they always want to see what’s in the back. I’ve realized that unless they’re decorators, people need to see how you can live with the pieces.”

Stools and a sconce by Green River Project

An arrangement of 20th-century African figures.

The concept of a hybrid space in which he could live and work always appealed to Bargo, but the road to opening an official gallery evolved organically. “I’m really social and I love entertaining,” Bargo says. “I love to have people here who aren’t even necessarily shopping for anything and who just want to chitchat about furniture. When I was in Brooklyn Heights, a lot of decorators or architect friends would come over and be like, ‘Oh, I love that table!’ And I’d be like, ‘Well, it’s available!’ I don’t really have a sentimental attachment to objects, so I can live with something for just a few months. It became a thing where people would email or text and ask if they could come by on a Tuesday afternoon, and we would sit and have tea. That’s kind of how the dealing part came about.”

His career as an interior designer took a more traditional path. Bargo grew up in Corbin, Kentucky, a tiny town of eight square miles near the Tennessee border. When he was in fourth grade, his parents moved into a new house and hired the only decorator in town. “I was so fascinated by the whole idea,” Bargo says. “I sat in on every meeting, and I still distinctly remember the smell of the wallpaper and Scalamandré fabric books he would bring.” Bargo’s parents weren’t aesthetes—at the time, his father was a state police officer and his mother a schoolteacher—but soon the entire Bargo clan had the decorating bug. “My mom started getting Architectural Digest and Southern Accents, and I would take boxes, wrap them in white printer paper, and tape rug or furniture ads from the magazine to make these little dollhouses. And I repainted my room every year. Before I left for college, it was all hunter green and Ralph Lauren tartans—so not my aesthetic now.”

Bargo, with his dog, Temo, and Mary T. Smith’s The Way to Be Good, 1980, as well as a 20th-century African stool, a Mathieu Matégot chair, and a Pierre Jeanneret screen.

Bargo wears a top and T-shirt from the Row; Hermès pants; Vans sneakers; his own hat.

Bargo, with his dog, Temo, and Mary T. Smith’s The Way to Be Good, 1980, as well as a 20th-century African stool, a Mathieu Matégot chair, and a Pierre Jeanneret screen.

Bargo wears a top and T-shirt from the Row; Hermès pants; Vans sneakers; his own hat.

Bargo moved in 2004 to New York to attend the New York School of Interior Design, and after graduating worked for the decorator Thomas O’Brien at Aero Studios. O’Brien’s sensibility tends to run more mainstream than modernist, but for Bargo the experience was invaluable. “At that time, Thomas had a staff of about 35 people and was doing a Target collection, fabrics for Lee Jofa, and several furniture lines. It was through him that I truly understood that interior designers could also do product development or licensing, that there were stylists, editors, and people who produced the stories. That’s when I started thinking about different avenues I could get into besides decorating.”

Bargo doesn’t have much interest in product development, though. He once designed an angular pine side chair and painted it glossy black, but “I’ve shown it to people and no one’s actually ever wanted it,” he says, laughing. “I think people come to me expecting things from cool designers or significant name pieces, and when I’m like, ‘I did this,’ they’re like, ‘Erm, okay.’ ” In the past few years, however, Bargo has begun exploring a new phase of his career: fostering young talents like Joseph Algieri, Tino Seubert, and Ian Felton, through a rotating series of exhibitions in his space.

In Bargo’s living room, a custom sofa, a table by Gio Ponti, 20th-century African figurines, a Danny Kaplan Studio lamp, a 20th-century African stool, and a chair by Jean-Paul Barray and Kim Moltzer.

The first one was a solo show by Green River Project, a New York furniture studio cofounded by the art-world expats Aaron Aujla and Benjamin Bloomstein, whose conceptual, hand-hewn pieces often riff on works by Bargo’s beloved French favorites. “Aaron and I met on Instagram, as one does these days, and we became fast friends,” Bargo says. “I knew I was leaving the space on East Broadway, so I said, ‘Why don’t you do your first show here?’ It turned out to be a hit.”

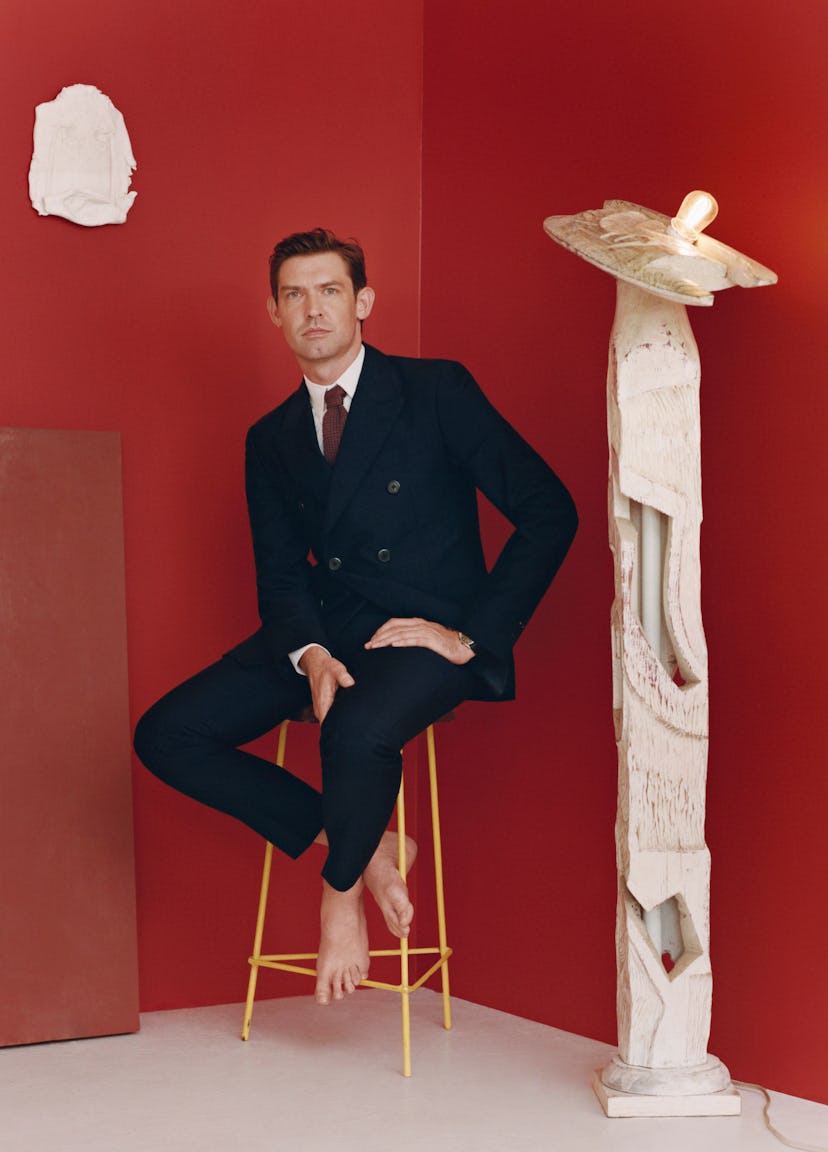

Michael Bargo wears a Prada suit; the Row T-shirt; Falke socks; his own watch and sneakers.

The reference point for the exhibition was Le Corbusier’s Cabanon, a seaside cabin that the Swiss-born French architect built for himself in 1951 on the Côte d’Azur. “We imagined someone living in a remote setting and all the things they’d need,” Aujla says. “We designed a daybed from lacquered wood and patinated brass, and a desk from the same materials; a Formica wardrobe with a bamboo hanging rod; an icebox for champagne; and a screen. Michael gave us free reign for what we wanted to make, and then we came back together about styling it and how things would be situated in the space.”

After the event, the three continued to work closely, with Bargo hiring Green River to work on his own kitchen with Corbusier-inspired laminate panels glued to the fridge and hand-carved cabinet pulls from Green River’s forthcoming hardware line. They’re currently planning a second show for later in the fall, and Aujla sees Bargo as a forever collaborator. “There’s a certain elegance in his approach that really feels like it’s missing in New York City,” Aujla says. “There’s a time and a place that Michael romanticizes—French midcentury—and what he does best is to imagine what that would look like today.” Aujla isn’t the only one to praise Bargo; to scroll through Bargo’s Instagram posts is to encounter a string of heart-eye emojis from friends and clients.

A sitting area in Bargo’s apartment, with Roger Herman’s vase *Untitled, 2007*, a Serge Mouille lamp, 20th-century African masks, a Charlotte Perriand table, and Pierre Jeanneret chairs.

With his cleft chin, permanent stubble, and penchant for casual clothing, Bargo has a tendency to look somewhat aloof in portraits, but in person he has a quick smile and a gracious, self-deprecating manner. During the course of our conversation, he frequently uses the word “wild” to describe not only the way furniture looks but also how he got to this point in his career. You get the feeling that Bargo will always feel like what he calls “the little guy in this business.” When asked if he aspires to participate in the bigger fairs, in light of a 2018 showing at Collective Design, he shakes his head no. “I can’t compete, and I don’t want to,” he says. “I don’t want a big gallery space with huge overhead and a big staff. I like having a smaller operation; I like being close to my clients. I would love to live in Europe at some point, but I’m having so much fun right now. I’ll ride this as long as I can.”