Malcolm David Kelley, Little Boy From Lost, Washes Up As a Young Man in Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit

The 25-year-old actor who broke out as Walt Lloyd in Lost is back, and definitely grown up.

It’s been 15 years since the actor Malcolm David Kelley made his feature-film debut in Antwone Fisher, eight years since his last film role, in Mississippi Damned, and six years since his last starring role on a screen of any sort, in Teen Nick’s Gigantic. So with his turn in Kathryn Bigelow’s new historical drama Detroit, the 25-year-old actor—still perhaps best known for playing the child castaway Walt on ABC’s Lost—is making an auspicious return to the big screen.

In Detroit, which premiered Friday, Kelley plays Michael Clark, one of nearly a dozen young black men staying at the Algiers Motel during the Detroit riots of the summer of 1967. One night, while Clark and several other men are playing music and playing with a starter pistol in a motel room, a contingent of Detroit police officers raids the hotel in search of a shooter. Over the course of a single evening, the cops embark on a reign of terror, playing what’s later referred to as a “murder game” that leaves three dead. Kelley features alongside a cast that also includes John Boyega, Will Poulter, Hannah Murray, Anthony Mackie, and Samira Wiley. The Algiers Motel incident, as it has come to be known, is the central drama of the brutal, claustrophobic Detroit, whose power lies in its unblinking appraisal of details that evoke more recent incidents of police brutality—the gun the police were allegedly searching for (just a toy), the victim purportedly lunging at an officer’s gun (shot in the back).

“It’s definitely a mirror reflection of what’s going on today,” Kelley said, drawing parallels between the acquittal of the three officers in the Algiers Motel incident and recent failures to indict. Even as Detroit was filming last summer, the country confronted the daily onslaught of new such cases like deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. “The court systems are still not helping us be able to see justice, so it’s frustrating,” he said. “We’ve made a little progress,” he added, but still, he wondered, “How are we still living in this reality right now?”

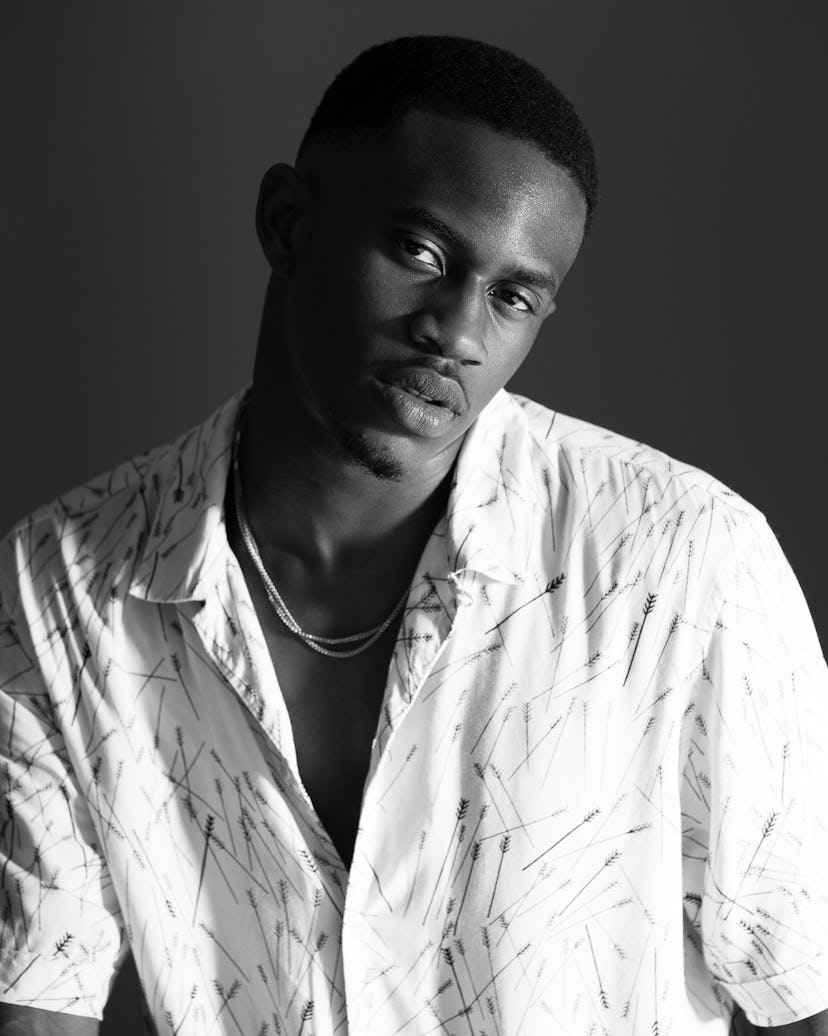

Photo by Myles Pettengill for W Magazine, styled by Gabrielle Langenbrunner.

Detroit might be Kelley’s first part in years, but during his acting hiatus, he hadn’t gone entirely dark: Instead, he retreated from the screen—only accepting the occasional guest spot on television—to write, record, and tour as one-half of the pop outfit MKTO with his Gigantic co-star Tommy Oliver. He had aspired to be a musician from a young age, and the five years he spent in the studio and on the road with MKTO “also gave me time to grow up from that boy-to-man stage,” he said, which “can sometimes be awkward—coming from being a young actor.”

Indeed, Kelley remains perhaps best known for parts like Antwone Fisher, in which he played the title character at age seven (observing Denzel Washington making his directorial debut, Kelley reported, whet his own aspirations to go behind the camera). Then there was Lost, the hit ABC drama in which he played Walt Lloyd, one of the original castaways of Oceanic Flight 815; Kelley had edged out other young hopefuls, in part, because of his performance in Antwone Fisher. (He filmed both before he even hit puberty.) He departed Lost before it finished its run in 2010, turning to Gigantic and then MKTO—and now, a new slate of grown-up roles, including Detroit and a guest spot on Issa Rae’s Insecure.

Kelley had just returned to Los Angeles (a Long Beach native, he now resides in the San Fernando Valley) during a lull in MKTO’s touring schedule when casting director Victoria Thomas, fortuitously, called him in to audition for what was then simply known as Untitled Kathryn Bigelow Project. He read scenes from movies like Ray, the project still shrouded in mystery—“It was kind of unorthodox,” Kelley recalled—and soon, he was performing a screen test for the director herself. They improvised a scene from the film (at that point, he knew the film dealt with police brutality), but it wasn’t until Kelley had boarded a plane en route to the shoot in Boston that he received his script and grasped the full scope of the project.

Despite recent criticism—Detroit, a film about the horrors an overzealous, predominantly white police force inflicted on black Americans in 1967, was written and directed by Mark Boal, a white man, and Bigelow, a white woman, and some observers have noted a lack of depth to the narrative of its black characters—Kelley said he had no qualms about the direction of the film: “Understanding the platform Kathryn has,” he said, “I think it’s beautiful she decided to take on a story like this. This is her type of work.”

Observing Bigelow at work has also been informative for Kelley’s own directorial aspirations. She and cinematographer Barry Ackroyd arranged the set lighting in a way that required fewer cuts between scenes, immersing the cast in the action. “We were really living it,” Kelley recalled.

But in addition to getting behind the camera, Kelley has leading-man ambitions: He has his eye on a variety of genres including comedy, war drama, and Marvel blockbusters. (He cited Black Panther, which is Marvel’s first feature film to star a black superhero, as particularly boundary-pushing.)

“Being a part of a film like Detroit,” he said, “People are like, ‘Oh, what’s next?’”

Chris Hemsworth thinks Charlize Theron should be the next James Bond: