Everyone gets one gift, and for Lyor Cohen—the charismatic, six-foot-five chairman of Warner’s Recorded Music division—that gift is presence. Spending an evening with him is like climbing aboard a bullet train: Stories, people, cityscapes go streaking by, with only Cohen’s face and voice in focus.

I’ve just walked into the 52-year-old’s six-story town house right off Fifth Avenue in the East Nineties. Thirty years ago, Cohen washed ashore in Manhattan with nothing in his pockets; now, having taken hip hop from dance halls and dub tapes to international ubiquity, he has become a card-carrying member of the New York social scene, largely due to his relationship with preppy-luxe designer Tory Burch. I’ve come to see him on the other side of the rainbow.

He puts a drink in my hand and heads down the hall, gin in fist. “I’m gonna give you a treat,” he announces, settling into his champion-size living room and crossing his long legs. In an exquisite, Bond-villain moment, he presses a keypad: bulbs dim, blinds lower, and the only light in the room shines on a Gerhard Richter painting—a nude descending a staircase. “If it was four in the morning? And we had just listened to a good piece of vinyl? And we were really, really happy? She looks like she’s walking downstairs into the room.”

During Cohen’s initial two years in New York—he arrived via the bohemian Los Angeles enclave of Los Feliz in 1982—he slept on the floor of a welfare hotel. Some evenings he toured the Upper East Side’s leafy, quiet streets; the journey from sidewalk to master bedroom still surprises him. “I used to walk by these town houses—you know, they’re so beautifully lit—and ask myself, Who lives here? How is this possible?” Years later, after he bought one of his own, his social-activist mother toured the place with a scowl: “‘This is not how I taught you to live.’” But that’s not all she said, Cohen is quick to note. “After she berated me, she says, ‘Okay—where am I sleeping?’ My mother loves staying at my house.”

On Cohen’s office wall is a framed edition of Captain America, issue No. 100. “He was invented to kill Hitler,” Cohen explains. “By a Jew.” He steers me to a photo of himself at 13, with a big head of curly hair: “A four-day bar mitzvah, in the Sierra Nevada. My dad was the rabbi.”

Around the same time as the bar mitzvah, Cohen began visiting his older brother, a teacher in South Central Los Angeles. At halftime during the school’s basketball games, kids would roll out a drum set and a bass, and Cohen would receive a kind of insider trading tip: an embryonic version of rap. “I knew something important had happened,” Cohen says. He went East for college, returned West to take a job in a Beverly Hills bank, and worked promotions on the side. Borrowing $700, he booked Run-DMC at the Stardust Ballroom in Hollywood, pocketed $35,000 in a single night, and headed back East again—he’d spoken to a man named Russell Simmons who was starting a music label.

From left: Speaking at his bar mitzvah in 1972 (the rabbi is his father); working as Run-DMC’s road manager.

At Simmons’s company, Cohen set about making himself indispensable, toting boxes, answering phones. Rap was the music of the city, but major labels weren’t interested. The members of Run-DMC were heading to the airport for a European tour when their road manager vanished into the drugs-and-parties ether. Cohen said, “I have a passport,” and spent the next three years on the road as the group’s manager, learning the industry from the ground up. “Three years, nonstop, all over the world. We never missed a gig. Flying coach, back of the plane. Staying at the worst hotels.” Within a few years, Simmons’s Def Jam Recordings began to run up the scoreboard with a string of hits by the likes of LL Cool J, the Beastie Boys, and Public Enemy. In 1988 Cohen became its president.

Here’s the sort of thing he learned to do: In 1986 Run-DMC released a track called “My Adidas.” No special reason; they simply loved the sneakers. Cohen phoned the sportswear giant’s head of American marketing and invited him to a Run-DMC show at Madison Square Garden. From the stage, Run made a request, and an arena of 30,000 people raised their Adidas shoes in the air. The Adidas man found himself crying, and Cohen signed rap’s first endorsement deal—for a million bucks.

He walks me into his bedroom. It’s the bedroom—the house—for anyone who’s ever dreamed of living full-time in a hotel: impeccable taste without being anyone’s specific taste. I tell him it’s beautiful. Cohen nods. “Isn’t that nuts? It’s nuts.” And I realize I’m in a novel, standing beside Jay Gatsby while the young tycoon, with a touch of wonder, shows me his marble staircase, his Savile Row shirts.

In 1999 Def Jam was sold to Seagram for $135 million; Cohen, at 39, was a rich man. He stayed on as the new company’s president and bought this house; Newsweek called him “Rap’s unlikely king.” In 2004, Seagram’s former chief, Edgar Bronfman Jr., wooed him to Warner Music.

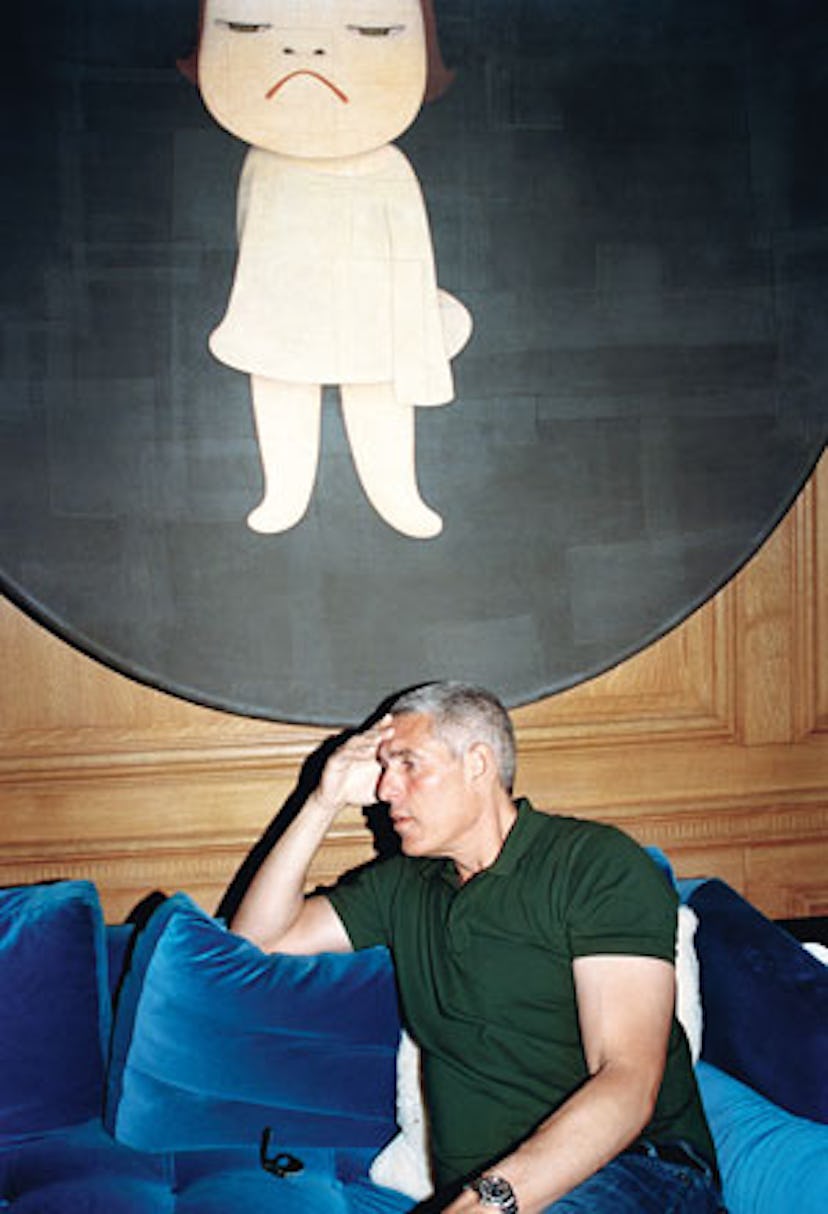

Cohen brings me into his daughter’s room: a telescope, a painting by Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara, a poster of Houdini. However, since Cohen and his wife of 13 years, Amy, split in 2006, he has lived in the house alone. “You can smell it, too—that no one’s here,” he says. Most nights, he heads down to the Pierre hotel, where Burch lives.

In 2009 Cohen and his ex-wife sold another property they’d owned together, an Upper East Side duplex. Almost symbolically, it went to an executive from Google. The change to digital has chewed through the music industry. Characteristically, Cohen sees the shift as an opportunity. “I’m excited,” he says, “because I used to do a mickey on you, right? I used to produce one hot joint, and I locked it up on a $19 CD. You can bifurcate my shit now. The digital era is simply power to the consumer. So I can just sell the hit, or I can go into long-term artist development and build something really sticky and important. The creation of the real stuff, the good stuff, is the thing that will yield.”

From top: Cohen grabs a pre-gig bite at Katz’s deli; from left: with Tory Burch at this year’s American Ballet Theatre opening gala; Gerhard Richter’s Ema (Nude on a Staircase) in a corner of his living room.

This leads to the second response to digital—a strategic approach called 360. The idea is essentially this: When an artist signs with Warner, the company becomes his or her partner in everything. The concept came to Cohen five years ago at a concert at Madison Square Garden, and it’s a management story that sounds like a parable: “I’m with my son, Az; he’s 12 years old at the time. The whole place is sold out, and he says, ‘Dad, I’m so proud of you. Look at all these people. Look at the action you’re getting a piece of.’ I lean over and say, ‘I don’t have any action.’ And he looks at me with such disappointment—it was ridiculous. So we leave the venue, and he goes, ‘Dad, they’re 10 deep at the merch booth. Don’t worry—at least you have action there.’ And I felt that small. That’s when it all just clicked for me; that was the end of that bullshit.”

Under 360, 10 percent of Warner Music’s revenues now come from what the business press calls “nontraditional” sources. This past May the company was sold to Access Industries, a conglomerate headed by Russian-born Len Blavatnik, for $3.3 billion in cash. Blavatnik is a Cohen friend, and Cohen came with the company.

We’re now back in his living room—a room, Cohen tells me, where Neil Young danced after his brain aneurysm surgery with “cords coming out of his head.” I ask to hear more about Cohen’s business approach. This time, what comes out is the Bible. “I show up,” he says. “When God first introduces himself in the Bible—now, can you imagine the guys who wrote that book? You think they just randomly came up with the words? Or do you think it took weeks, months, maybe years to figure out, What is God going to say to man?—first words he says: ‘I am here.’ I am here. Imagine. And that is so powerful now, in the digital world, where you don’t have to show up. It’s inconvenient. It’s far away. It oftentimes doesn’t fit into your schedule. But there’s so much information there. I show up. Period. End of subject.”

A Cohen day is a crowded day. It’s after nine, and he needs to attend a concert by Death Cab for Cutie, whose new album he has just released. We pile into a chauffeured Mercedes minivan—“This is not my car,” Cohen says, without further explanation—where I experience the thrill of watching Cohen swallow music. “So now I’m gonna play you a joint,” he says, and his whole delivery changes: His big ears seem to expand; his head swings side to side. When we pull up at the Bowery Ballroom, the bouncer—a slab-shouldered African-American with a Dostoyevsky beard—knows Cohen on sight: “What’s up, brother?” They shake. Cohen asks, “Is this the fastest way through? I wanna go right into the show.”

At a Coachella show earlier this year.

Once inside, Cohen threads his way to the VIP balcony. Not long afterward, though—far before the lights come up—he has vanished: another show, another call, another obligation. A Warner executive downstairs grins: “He poofed on you, huh? That’s what Lyor does—he’s always got someplace else he needs to be, and he vanishes. He goes poof!”

A week later, Cohen is at an Upper East Side benefit for the arts and education charity Boys & Girls Harbor. Men and women, suits and jewelry, hail him from across the room. “Lyor! Lyor! I want you to meet—” and Cohen becomes a handshaking machine. Waiters circulate through the crowd with silver trays crammed with hors d’oeuvres like tiny, unclosable suitcases. He has brought his mother and son. Az has his father’s height and features, his watchfulness. Cohen’s mother is formidable; you understand how rough it might be to have her disapprove of your house. Cohen seems to be running for office—either to be Cohen or to be allowed to stay Cohen. When he looks my way at all, it is with pity: Why aren’t I extracting as much fun, as much interest from life as he is?

Guests file into the Heckscher Theater, and the performances start. An earnest boy and girl sing Pippin’s “Corner of the Sky”; Yo-Yo Ma plays. Then a teenage student steps onstage. A ripple goes through the crowd: The girl, statuesque and beautiful, emits a star quality. Cohen sits up straight, leans over, and whispers, “Don’t let her sing like Mariah Carey and have me sign an act tonight.” The girl takes a breath; Cohen listens closely. She sings, and as the applause begins, he turns and says with a smile: “Not gonna happen. But you never know. You have to show up, right?”

Cohen at Katz’s and his home: Graeme Mitchell; Coachella: Theo Wenner; Cohen with Run-DMC and Bar Mitzvah: Courtesy Of Lyor Cohen; Burch and Cohen; Rodin Banica/AP Images