Liv the Life

In 1975, while making her Broadway debut in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, Liv Ullmann learned that Ingmar Bergman was coming to town to see her. Bergman’s muse, collaborator and former lover, Ullmann had starred in many of the Swedish auteur’s greatest films, and knowing that her new friend Woody Allen idolized Bergman, she offered to introduce them over dinner. But when she, Allen, Bergman and Bergman’s fifth wife, Ingrid, sat down to eat, the two “geniuses,” as she calls them, barely spoke. “Seriously! They did not talk,” she says. “Ingrid and I kind of talked about food or whatever, and they looked at each other, eating and smiling.” She was a little surprised, then, when afterward in the car, Allen confided to her how thrilled he was. “He almost cried,” she says with a gutsy laugh. “And then the moment I got home, the phone rang and it was Ingmar, saying, ‘Oh, Liv. Thank you. That was really great!’”

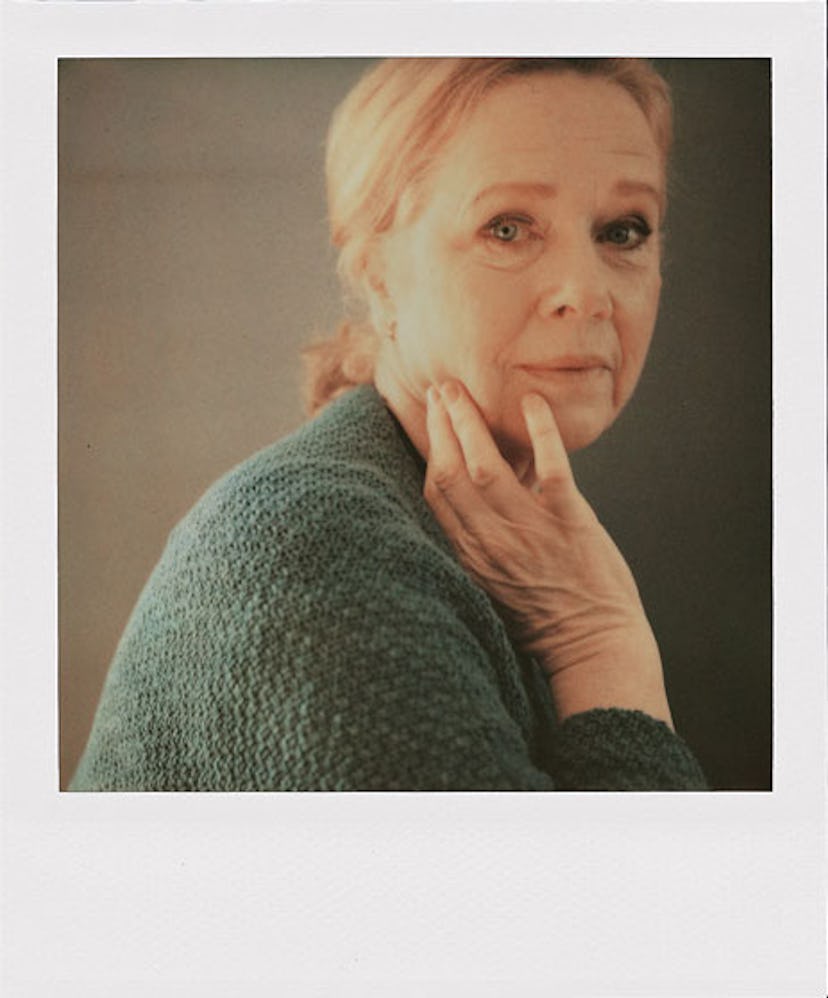

Thirty-four years after that evening, Bergman stories still pepper Ullmann’s conversation. Given the pair’s history, it’s not surprising. The two fell in love while making their first film together, the groundbreaking Persona (1966), and though their romance lasted only five years, their alliance continued until his death, in 2007. Now a feted director in her own right, Ullmann is in New York on this summer afternoon to begin work on her revival of A Streetcar Named Desire, which stars Cate Blanchett as Blanche DuBois and marks Ullmann’s American stage directorial debut—at 70.

Her seasoned perspective, says the native Norwegian, gives her insight into the play and the doomed, delusional Southern belle at its core. “I have the experience of age and suffering,” she says, seated in an office at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where Streetcar arrives in November after its U.S. premiere at the Kennedy Center. “I have a well they can use.” Like the trapped housewife Nora in A Doll’s House and the deceived spouse Marianne in the film Scenes From a Marriage—two of her best-known roles—Tennessee Williams’s characters, she observes, struggle to be understood. “Most people feel they are looked at and not seen,” says Ullmann, who looks you straight in the eye when she speaks, lulling you into an easy intimacy. “If you are not recognized, you sometimes do strange things to be seen.”

Ullmann had planned to direct Blanchett in a film adaptation of A Doll’s House, but funding fell through. Then one day over breakfast in London, Blanchett’s husband, Andrew Upton, proposed they do Streetcar for the Sydney Theatre Company, where Blanchett and Upton serve as artistic directors. “There’s a nakedness to Liv—a very thin membrane between her and the world,” says Blanchett midway through rehearsals in Sydney, where Streetcar is due to premiere in September. “Often as actresses move through their careers, the mask can get thicker and thicker, but Liv keeps that very febrile, raw relationship to emotions and relationships and encourages that in her actors.”

Though now lined, Ullmann’s face retains the beauty it had when Bergman scrutinized it with his camera to record the vulnerability and sensual intelligence she so naturally projects. Aging, however, has affected her career choices. She confides that when approached to play Mikhail Baryshnikov’s ex-wife on Sex and the City and George Clooney’s ex in one of the Ocean’s films, she turned down the roles because she feared seeming too old for them. “I didn’t want to get off the plane and see the shock on the directors’ faces, thinking, My God!” she says, laughing but not kidding.

It’s the kind of confession you’re unlikely to hear from a film star, but then little about Ullmann is conventional, beginning with her relationship with Bergman, with whom she had a daughter, Linn, in 1966, while married to someone else. Ullmann was 27, Bergman 48 and already the father of eight children by five women. The pair lived together for three years on the remote Baltic island of Fårö, in a house Bergman built, and each day, on the door to his study, they inscribed hearts, tears and other symbols of their feelings for each other. There they also made two more classics, though the director’s need for control proved suffocating. “Violent and without bounds,” Ullmann later wrote of his jealousy in her memoir, Changing. “Nothing existed outside ourselves.” Looking back now, she says, “We had a little child there, and he didn’t want people to visit, and he didn’t like me leaving either. It was very tough.”

Her passport to Hollywood came via another Swedish director, Jan Troell, whose The Emigrants (1971)—about a Swedish couple newly arrived in 19th-century America—won her a Golden Globe and the first of two best actress Oscar nominations. (The second was for Bergman’s 1976 Face to Face.) Ullmann landed on the cover of Time and shot four movies in quick succession, most of them duds. “I made poor choices,” she concedes, like the bizarre musical Lost Horizon (later nicknamed “Lost Investment”) and the silly 40 Carats, in which the 34-year-old Ullmann was cast as a frustrated older woman dating a much younger man. “The guy meant to be 20 years younger than me [Eddie Albert Jr.] was only about one year younger,” she says. “Everything was wrong.”

Soon after, she returned to Europe and followed up with the searing Scenes From a Marriage (1973), the semiautobiographical Bergman work she deems closest to her heart, playing a woman who learns her husband is having an affair. The film was shot on Fårö, where Bergman was then living with Ingrid. When asked if it was difficult to make, given the subject matter, she replies, “It was a great time,” noting that despite Bergman’s reputation for bleakness, “he had a wonderful sense of humor. Of course many people can’t believe that, seeing his films, but he had a big, strange laugh and he wanted to laugh. We who worked with him were all playmates. For Ingmar, this was so important. On his sets there was so much joking around. We told each other everything about ourselves. I have a picture from that time and Ingmar has written on it, ‘Here we are playing again.’”

She feels lucky to have been “seen,” as she puts it, by Bergman, who she says often used her in his work as his alter ego. (He even intended for her to play the mother in his Oscar-winning Fanny & Alexander, but she turned him down to do a Norwegian film, a decision she regrets.) “In most partnerships, you never get to have a complete understanding of the other person and use it creatively,” she says. “And he did that with me, even if he stole some of my life for Scenes From a Marriage.” Recently she discovered that for a devastating scene in which the husband falls asleep while his trusting wife reads her diary to him, Bergman had taken the words directly from a journal she had left for him to read while they were living together. “It made me cry when I realized it,” she says. “I had no idea.”

Given Bergman’s long shadow, Ullmann says she once worried that “I’m nothing outside of him,” but eventually came to see how she stood out on her own. She raised their daughter, now an acclaimed novelist and one of Norway’s leading journalists; starred on stages around the world; and worked as a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, later cofounding an organization for refugee women and children. These days she divides her time among Oslo, Boston, and Key Largo, Florida, and reportedly lives with Donald Saunders, the Boston real-estate developer she married in 1985, divorced a decade later and reconciled with the day after the papers were signed. (Though Ullmann refuses to discuss him, Saunders accompanies her to today’s interview.)

In 1992 Ullmann turned to directing and freely admits that she drew on many of Bergman’s lessons, “mainly that you can play, use fantasies, everything you did as a child,” she says, noting that she never valued how creative she’d been in front of the camera until she moved behind it.

“Even though she has this vast body of work and a depth of experience that’s almost unparalleled,” says Blanchett, “she’s still able to keep that sense of wonder alive in her work.” Streetcar, Blanchett points out, “sits in the shadow” of the 1951 film version starring Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh: “You have to remove all the preconceptions and clichéd relationships one has to it and come to it fresh. I can’t imagine any other director doing that as fearlessly as Liv has done.”

Ullmann’s first two features were lavish period pieces, but she achieved international renown as a director when she tackled two Bergman-penned screenplays, both drawn from his life. Private Confessions (1996) looked at the unhappy marriage of Bergman’s parents, and Faithless (2000) at the destruction wrought by a woman’s affair with her husband’s best friend. Faithless starred Ullmann’s Scenes From a Marriage costar Erland Josephson, and between takes, the two old friends would joke around as their former characters, Marianne and Johan, imagining them demented 30 years later. “We shot a few scenes [of themselves as Marianne and Johan] and sent the footage to Ingmar, and he loved it,” she says. “But after a year there came this script, and it wasn’t funny anymore. It was as dark as any movie he made.” The resulting TV film, Saraband (2003), was Bergman’s last. Ullmann reprised her role as Marianne, who visits her ex at his summer home after 30 years apart. When he asks why she has come, she replies, “You called for me.” “I just loved that,” says Ullmann.

When Bergman was dying on Fårö, Ullmann traveled from her cottage in Norway to see him. He died soon after she arrived, but she made sure to tell him, “You called for me.” Says Ullmann, “I got to say goodbye to him. I don’t know if he knew I was there, but it was important for me.”

She still longs to do her first comedy and says Bergman kept promising to write her one. But it’s doubtful there will be many laughs when she plays the drug-addled Mary Tyrone in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night at the National Theatre in Oslo in 2010. She’s excited about returning to her roots on the Norwegian stage after a 39-year absence and even about touring the north of the country by bus with the production, something she hasn’t done since she was a fledgling actress. “It will be wonderful,” she says with girlish glee. “A kind of return and farewell. I will have come full circle.”