The Lil Peep Movie, Everybody’s Everything, Splices Together a Tragic Picture

The Lil Peep movie is about to be released (as is an album of the same name).

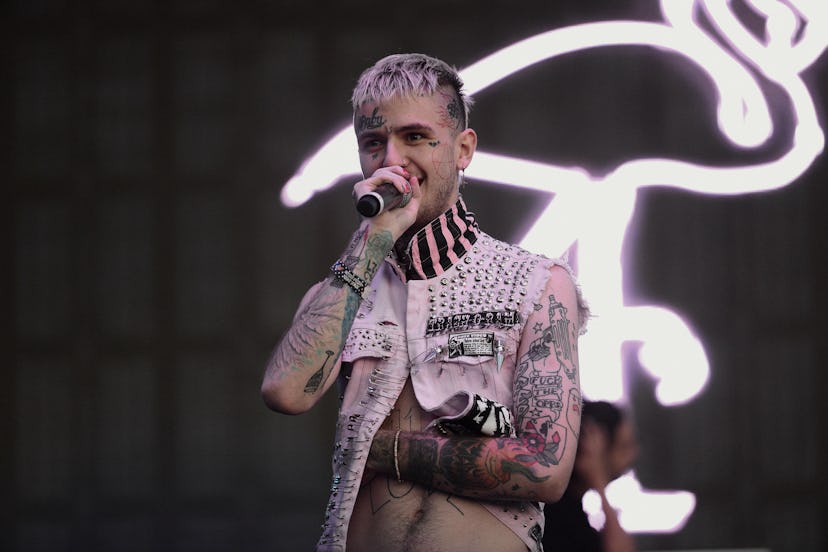

In Everybody’s Everything, the new documentary out on November 15 about the late Gustav “Lil Peep” Åhr, it is said that the ill-fated musician—who died of an accidental overdose of fentanyl and Xanax in November of 2017, just after he turned 21—was anti-capitalism, and that he had aspirations to dismantle the commercial hierarchies of the music industry.

That sentiment can (and often does) come across as a naif battle cry of the young and, even if scantly, the privileged.

But for a few moments in the film, the conviction feels real, or as real as something can be when shrouded in hazily colorful, messily voyeuristic entropy; Lil Peep initially gained popularity through the hosting and streaming service SoundCloud, entering the music business through a non-traditional (albeit more and more common) access point. He garnered a passionate fan-base, from suburban Long Island, New York (where he grew up) to Kazakhstan, before he had any sort of big-name management or record deal. He had never conformed, nor did it appear he ever would. He was able to carry and, even if shakily, commercialize the universal pangs of abandon and alienation into something self-acknowledging yet optimistic, something people within his reach could hold onto in an increasingly fraught post-2016 election world.

Yet the sentiment starts to lose its loft when it becomes apparent just how profound Åhr’s misinformed actions were. Everybody’s Everything is full of testimonials from those who were around the man, most everyone saying how special and gifted he was. But it’s a lot of telling, and far less showing. Here, at least, Åhr does not get a chance to live up to it.

What the viewer sees is a downward spiral from the starting block, a yielding to the negative trajectory as opposed to Peep’s potential, and, distressingly, very few people (if any) stepping into help. Drug use is shown, and drug use takes on a celebratory quality within Peep’s songs. For example: the track “Witchblades,” featuring Lil Tracy, features the sound-bite “cocaine, all night long / when I die, bury me with all my ice one.” Quite a few in his circle, rather, try to attach themselves to the Peep show train without attempting to pump Peep’s self-destructive breaks. It’s not a new phenomenon (Avicii comes to mind), but it is a sad reminder that it continues to happen.

Åhr was onto something—the nexus of “SoundCloud rap,” the prescient ability to combine musical stylings of a more emotional, pained wail of rock with hip-hop and trap, the face-tattoo-as-mainstream—but one is left feeling that, at the baseline, the things he said and the things he did were immature more than anything else. Even the doc’s title, taken from an Instagram post that Peep uploaded shortly before his death, hints at someone who had not yet understood the vast impossibility of the statement. Then again, how could he have? He was only just 21.

The saving grace of Everybody’s Everything are intermittent voiceovers of letters written by Åhr’s grandfather, and ostensible lifelong father figure, Jack Womack. Some may see them as a grayly saccharine binding structure, but the man is eloquent and reasonable. He felt for Peep. He did not judge Peep. And, through his words, the audience gets a sense of care and stability—maybe the only permanently stable figure Åhr had ever known. An early line is recited slowly and with audible concern, enough to make one feel the force of Åhr’s tragedy: “My tattooed poet and sweetheart.”

Related: They Came From SoundCloud: Lil Uzi Vert and the 6 Rappers Who Could Be Rock Stars