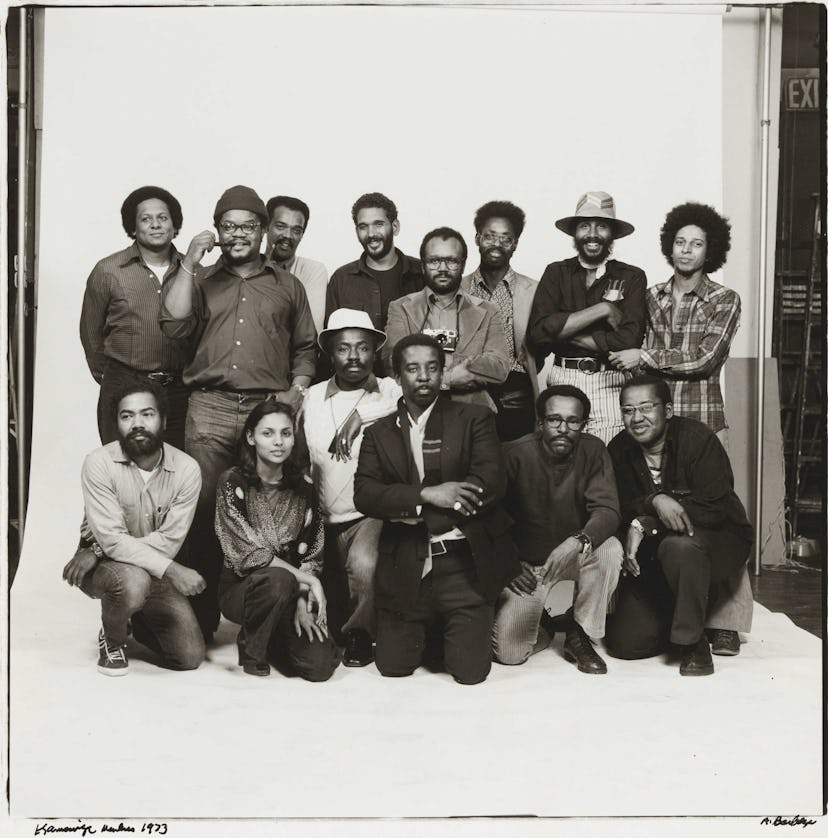

A New Exhibition Explores the Legacy of the Kamoinge Workshop

The curator of the Whitney Musuem show and surviving members of the Black photography collective reflect on the group's mission and impact.

The photography collective Kamoinge Workshop has been quietly documenting life for the last 50 years. The 14 artists who founded the group in 1963 had varying practices and visions, but were united by a desire to discuss, critique and improve their work. A culture of mutual care and investment came out of the Black communities these artists were raised in: Kamoinge’s purpose was to build together.

This month, an exhibition devoted to the Kamoinge Workshop opens at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The show, an emotive collection of roughly 140 photographs, traveled from the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, where it was initially organized by Dr. Sarah Eckhardt and her team. Eckhardt and Kamoinge crossed paths fortuitously in 2012, when founding member Lou Draper’s sister, Nell Draper-Winston, came to her with a box full of images and a story. “I fell in love with his photographs immediately,” Eckhardt says. “This story needed to be told, but it also needed to be told with Lou Draper’s voice.”

Shawn Walker, Easter Sunday, Harlem (125th Street), 1972. Courtesy of the artist and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Photography Committee, the Jack E. Chachkes Endowed Purchase Fund, and the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation 2020.61.

“Kamoinge” means “a group of people acting together” in the Kenyan Kikuyu people’s language. Taking action was central to this group. They met irregularly, sometimes every week, and within this loose structure, ideas and support blossomed. In the 1960s, in New York City and in the cities where Kamoinge’s various members hailed from, Black people were becoming more of a “social interest.” But the people assigned by magazines and newspapers to capture elements of Black life were rarely Black. “Who can better talk about us than us?” says Tony Barboza, one of the living members. Claiming agency for themselves was vital, both historically and spiritually. “It wasn’t so much that we had to get noticed. It was more so that we loved what we were doing.”

Nine of the original members (Draper, Barboza, Adger Cowans, Daniel Dawson, Al Fennar, Ray Francis, Herman Howard, Jimmie Mannas, Herb Randall, Herb Robinson, Beuford Smith, Shawn Walker, Ming Smith, and Calvin Wilson) are still active. To them, the representation of their own community was less of a political statement, and more of a moral necessity.

Adger Cowans, Footsteps, 1960. Courtesy of the artist and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Aldine S. Hartman Endowment Fund, 2018.201.

Barboza found Kamoinge at 19, right before a stint in the Navy. He was drafted and unwillingly answered. With good fortune—and a touch of sophisticated maneuvering—Barboza spent much of his time in the Navy refining his skills behind the camera and in the darkroom. “After a few months in the lab, they made me the photographer for the station newspaper,” says Barboza. “I would spend my free time photographing around the neighborhood that I lived in.” Back in New York, Barboza couldn’t find a position with any white photographers, so he decided to strike out on his own. “My first job was working for Harper’s Bazaar, on the shop by mail section. They paid me $125 a month, but I did it. I was the first Black photographer at Harper’s Bazaar,” he says, matter-of-factly.

Ming Smith, America seen through Stars and Stripes, New York City, New York, printed ca. 1976. Courtesy of the artist and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 2016.241.

The members of Kamoinge weren’t concerned with validation, or being the first. There was and is no culture of exceptionalism. “I was all about the beauty of us,” Barboza says. The core focus was the work. The work, and the people. That extends to the next generation as well. “I believe in teaching us,” he says. Ming Smith has a similar song to sing. “Kamoinge introduced me to photography as an art form,” she says. “They talked about composition and light in terms I had never heard before. I started researching other photographers: Brassaï, Cartier-Bresson, W. Eugene Smith. [Kamoinge] gave me all the tools to become an artist or look at things from an artist’s viewpoint, not just a person who would take snapshots.”

Smith, Barboza and their brothers and sisters depicted Black life in all its facets, as an antidote to the brutal, inaccurate fantasy that white photographers applied to it. In the show, you get glimpses of life in New York City in the 60s, 70s and 80s. Friends turning corners on Harlem streets, church aunties in their Sunday best, children playing together inside and on sidewalks. We see intimate moments of Black love, tenderness, poetry and silence. We also see the artists themselves, in groups and alone (a particularly fun self portrait taken in a convex mirror, by Shawn Walker is included).

Beuford Smith, Two Bass Hit, Lower East Side, 1972. Courtesy of the artist/Césaire and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2017.36.

Joy is expressed through music, in numerous portraits of Jazz musicians in particular. One extremely special outlier is a 1978 portrait of Sun Ra by Ming Smith, showing the artist and his audience in blurred motion. Visitors can enjoy the whole gamut of Kamoinge’s work—from an early 1970 portrait of Grace Jones by Tony Barboza to entirely abstract photographs like Lou Draper’s Congressional Gathering (1959), which hints at the foolish and frightening hoods of KKK members. Working Together locks the visitor into the present through contemplation of the past. An incredibly wide range of human emotion and experience is displayed, with text guiding the viewer through a self-authored and impactful collective history.

The essence of Kamoinge’s mission is summarized simply in a statement they released alongside their first portfolio, in 1965, which is included in the exhibition catalogue: “The Kamoinge Workshop represents fifteen black photographers whose creative objectives reflect a concern for truth about the world, about the society, and about themselves.” Truth is what is to be found in this show—much needed at a time when the nature of truth is so hotly contested.

Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through March 28, 2021. Extensive archival materials have been digitized and are available on the Whitney and VMFA websites.