Josh Brolin

A year after his breakthrough performance in No Country for Old Men, this Hollywood renegade moves on to a role of presidential proportions.

When Josh Brolin last got into a fight—before, that is, his recent much publicized arrest in Shreveport, Louisiana, in July, at a wrap party for Oliver Stone’s hotly anticipated George W. Bush biopic W.—the then 27-year-old was in his rural hometown of Paso Robles, California. Times were different.

“Fighting used to be okay,” says a jocular Brolin, 40, over a breakfast of two fried eggs, sunny-side up, in a Westwood, California, diner. “My hometown is one of these places where you used to be able to fight, make up, then hang out with the guy and make a new friend.”

Brolin shaved his head for the filming of W. to accommodate various presidential hairpieces.

What happened in Shreveport isn’t exactly clear, other than that Brolin was arrested and sat in the holding tank until sprung on a $334 cash bond. The press originally described the incident as a bar brawl involving Brolin, costar Jeffrey Wright (who plays Colin Powell) and crew members. In the days following, blurring the overall picture, reports explained that Brolin was booked not for fighting but on the misdemeanor charge of interfering with an arrest. (Brolin had already been categorized as something of a brawler, and not without cause. In 2004 his wife, actress Diane Lane, called the police to their house during a domestic dispute. Brolin was hauled off and booked on misdemeanor spousal battery, although Lane never pressed charges and the couple later described the incident as a “misunderstanding.”)

The full disclosure may have to await Brolin’s arraignment in Louisiana on December 2, six weeks after W., in which he plays the title role, hits theaters. Brolin says with a rascal’s grin that he wants to tell his version of events “badly.” In fact, he mentions his jail stay within seconds of sitting down for breakfast, contrary to the normal celebrity-interview protocol of leaving touchy subjects until last. But after bringing it up, Brolin then says he can’t talk about the matter at all. “Let me put it this way,” he says, like a blackjack player sitting on an ace-king combo. “It was nice to be in jail knowing that I hadn’t done anything wrong. And it was maddening to be in jail knowing that I hadn’t done anything wrong.”

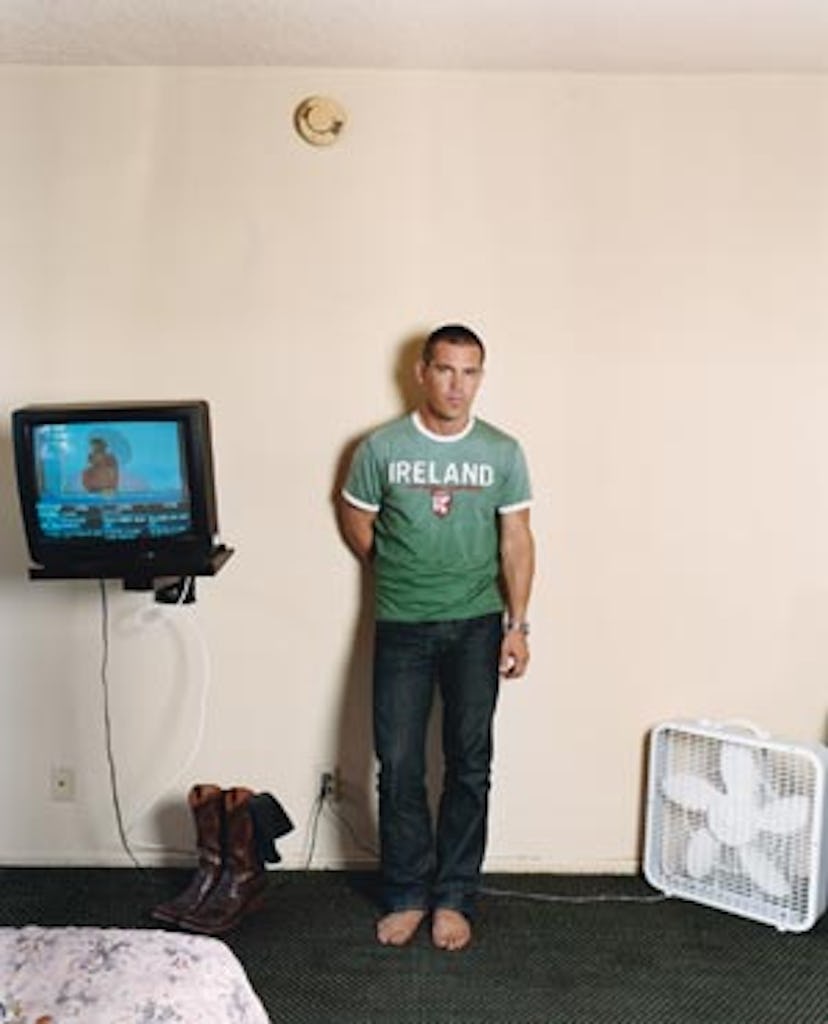

Exactly two weeks after the arrest, Brolin still looks jailhouse-tough. He lost 30 pounds to play Bush as a frat boy at Yale—“not because it’s cool to lose weight, but because it makes you look younger,” he notes—and his body appears sinewy beneath his tight T-shirt. He shaved his head to ease the discomfort of wearing various Bush-style hairpieces in the sweltering Louisiana heat, and with his hair still fuzz-short, he could pass as an offensive-line coach at an NCAA powerhouse. But if Brolin comes off as a good ol’ boy, he’s actually a Hollywood scion, the vigorous sprout of a six-foot-four tree named James Brolin. “My dad is probably one of the handsomest guys ever,” says Brolin. “I was making a joke and I said, ‘If I was a chick, I’d f— you.’ He was like, ‘You can’t say that! Shut your mouth!’”

As a young man, Brolin was far less sanguine. His father and mother, onetime casting agent Jane Agee, divorced in 1986. He says there was a “whole shadow thing” with his dad but nonetheless joined the family business, becoming a stage actor and cofounding a theater festival in Rochester, New York, in 1990. He married an actress, Alice Adair, in 1989, and the couple had two children before their divorce three years later. (Brolin and Lane wed in 2004.) During the five years that Brolin spent in regional theater, he recalls, he and his father figured out how to be friends again. Then, in 1998, “he goes off and marries Barbra Streisand,” Brolin adds with a guffaw. He says he enjoys “hanging out” with Streisand and his father at their Malibu estate and reports that the three even had an unplanned family reunion—at the hospital. Brolin was in to get a cortisone shot for a back injury, while the other two were there for a test he euphemistically describes as “an older person’s thing.”

“It was genius, man,” he adds. “I had this great conversation with them because they were both coming off the morphine or whatever cocktail they were given. It was good to see her without a few filters.” Contrary to a recent gossip report that Streisand was angry at her stepson for playing Bush, Brolin says, “She seemed very intrigued by the whole thing, really happy about it.”

Brolin as George W. Bush.

Despite his rugged appearance, Brolin has a demeanor as friendly and direct as a bluetick hound. It’s a wonder with his combination of talent and good looks that he didn’t hit it big years ago. Perhaps his pedigree worked against him in some way, causing Hollywood casting directors to, in Dubya’s own infamous expression, “misunderestimate” his potential. After debuting in The Goonies in 1985, Brolin spent the next 20 years playing small parts in good movies (Flirting With Disaster) and big parts in lousy ones (Mimic, Hollow Man). A spur-jangling appearance as Jedediah Smith in the Steven Spielberg–produced television miniseries Into the West hewed closer to his brawny image but did little for his big-screen stature.

Director Paul Haggis, who first met Brolin on the short-lived 2003 TV drama Mister Sterling, counters that the actor was just waiting stubbornly for the right role to come along. “He’s a picky son of a bitch,” says Haggis, who directed Brolin in 2007’s In the Valley of Elah and is planning to produce a feature version of the short film X, which Brolin wrote and directed. “Josh turned down roles other actors would leap at—big commercial roles—because he didn’t feel a connection with the character or the material. Even when he was going begging, he’d still say, ‘No, no, I can’t do a good job with that,’ and turn it down. Sometimes I felt like slapping him: ‘What do you mean you turned it down!’ But he was right. He had to do something that you’d remember him in.”

That indelible, careermaking performance came in the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men. Although Brolin wasn’t nominated for an Oscar to cap the film’s eight nominations (it won four), his tight-lipped performance drew nearly universal critical acclaim. Finely wrought appearances in Ridley Scott’s American Gangster and In the Valley of Elah—he played police officers in both—further bolstered the notion that this former Hollywood also-ran had emerged as a potential leading man. “Things are very, very, very different,” Brolin acknowledges. “I just had a meeting with my agent, and there was a moment as we were going through the projects when I was like, Wow. Wow! This is a very different place than I’ve been. Tony Scott wants to do this. Ridley Scott wants to work with me again.” Brolin was even offered the chance to earn a life-changing paycheck—to say nothing of the opportunity to connect with a blockbuster audience—by playing John Connor, one of the storied action heroes of modern cinema, in next summer’s Terminator Salvation.

Still, early this year, he passed on the part—Christian Bale eventually took the role—for what may amount to juicier screen time in smaller movies. November will see the release of Gus Van Sant’s Milk, about the late San Francisco city supervisor Harvey Milk (played by Sean Penn), the first openly gay man elected in American politics. Brolin plays Dan White, who murdered Milk in 1978. During the trial, White’s lawyers concocted what came to be known as the Twinkie defense—claiming that the defendant had been temporarily deranged after OD’ing on sugary junk food. “It’s interesting when you turn down a movie like T4, how many angry people there are suddenly,” reports Brolin, who took Milk to work with Penn, an old friend, and Van Sant, a directing hero of his. “They tell you, ‘Who do you think you are?’ I’ve gotten that forever, and so I’m fine with that.” Brolin pauses and shakes his head as if remembering some particularly energetic browbeating. “I love it,” he says with a broad smile.

From the outset, Brolin says, Penn confronted the potential nervousness of a group of actors playing flamboyantly gay characters by just steamrolling over it. (Diego Luna, Emile Hirsch and James Franco appear in the film as members of Milk’s entourage.) At their initial cast dinner, recalls Brolin, “the first thing [Penn] did was, he walked right up and grabbed me and planted a huge one right on my lips.” Brolin’s retelling of the moment registers as a tribute from one alpha male to another alpha’s impressive bravura.

As he talks, Brolin is spontaneous, funny and energetic, so it comes as a surprise when he confesses that he feels physically and emotionally spent after this year’s relentless shooting schedule. He explains that he went from the San Francisco set of Milk to Louisiana, where, for the first time, he had the responsibility of carrying a movie: As President George W. Bush, Brolin shot 103 of the film’s 108 scenes. The story derives its impact in large part from the young Bush’s almost mythic struggle to win his father’s approval and, later, to make his own mark on the world by conquering the old man’s geopolitical nemesis, Saddam Hussein. Brolin says that Stone approached him out of the blue with the role. “He just said, ‘I want you to do this movie,’” recalls Brolin, who figured the public wouldn’t want to see any more of their unpopular president at the cineplex, especially when presented by Oliver Stone. “My initial reaction was, ‘Are you nuts?’ There was a point where I actually grabbed Oliver’s head and said, ‘No!’ It was like I was talking to a dog or something.” Stone persisted, and when Brolin finally read the script, he found a richer and more intriguing interpretation of the Bush presidency than he had expected.

“It always seemed to me that he was the right person,” writes Stone in an e-mail, of his decision to cast Brolin. “Although classically handsome, I think he would consider himself a character actor first and foremost, and it was in this context that I thought of him as W. Josh certainly has star appeal and could be a leading man, but I don’t think he necessarily wants to be that. I think he really enjoys disappearing into a character.”

While avid readers of The New York Times op-ed page may hold the opinion that the two-term Bush presidency has been a tragedy, W. turns that political analysis upside down. “The thing I kept saying to Oliver was, ‘It’s a comedy, it’s a comedy, it’s a comedy,’ even though it’s not,” Brolin explains energetically. “You go through every emotion with it. It’s pathetic. It’s absurd. It’s darkly humorous. It’s exaggeratedly humorous.”

The script reads as a relentless and sometimes outrageous drama of an administration in love with neocon ideology and arrogantly dismissive of facts. But Brolin promises the film will rousingly and sharply satirize the Bush era. (“I‘d call it, if anything, something mixed between serious and buffoonish— a form of farce,” offers Stone.) Brolin mentions that the first day he played a scene in full Bush regalia, the crew actually cracked up, which he considers a high compliment. Still, the actor insists that he wanted to avoid making W. into a feature-length Saturday Night Live skit. He obsessively pored over news footage and scoured Bush biographies for insights into the president’s mind. To his surprise, he wound up liking the man behind the presidential seal, especially after Stephen Mansfield’s book The Faith of George W. Bush drew him deeper into the story of Bush’s religious conversion. As Brolin connected with what he boldly describes as Bush’s “humanity,” he came to believe that his earlier view of the president was superficial.

“It’s the most compelling story because you see this guy trying to find his niche. You see him fail and you see him succeed,” says Brolin. “Like it or not, good or bad. It’s perfect drama.”

When it’s suggested that Bush’s harshest critics may not agree and argue instead that the president succeeded only because of his surname, Brolin’s friendly demeanor goes suddenly stony. “That’s an impossibility,” says Brolin, with a hard and suspicious look in his eyes. “That’s like people saying that I have my success because my father was an actor.”

He acknowledges with a terse “of course” when asked if he can identify with Bush’s struggle to come to grips with a famous family name. But then, relaxing a bit, Brolin points out W’s ability to communicate with voters in the 2000 election, a skill that set him apart from his dad. In a final comment on the subject, one that seems to resonate with the echo of his own oedipal striving, Brolin adds: “He had more oomph than his father had.”