The Agony and the Ecstasy

Joaquin Phoenix, Bradley Cooper, and their very different takes on the business of being an actor.

“What are we doing?” Joaquin Phoenix asked me, with a mix of confrontation and self-disgust. “Is this what we’re doing? It’s nothing about you, but I don’t know why we’re doing this.” It was a beautiful Sunday afternoon in mid-October, the day after the New York Film Festival premiere of Her, in which Phoenix is wonderfully appealing, romantic, and vulnerable as a man who falls in love with his computer’s operating system. Phoenix, 39, was dressed in beat-up jeans, a dark zip-up hoodie, and boots that were untied. His hair was shoulder length for his role in Paul Thomas Anderson’s ’70s period drama Inherent Vice, which had just finished production in Los Angeles. As usual, Phoenix seemed both jumpy and curious. He was lighting up one American Spirit after another, which was part of the reason we were meeting on the patio of the hotel where he was staying, the Greenwich. I was there to interview Phoenix; he was there to smoke. Or so it seemed.

Phoenix was polite, especially to the waiter who brought us tea, and strangely endearing, but his code of personal authenticity does not abide talking to journalists. When I complimented Her, he waved me off and said, “I don’t want to hear it. You sound insincere.” When I protested and maintained that I genuinely loved his performance, he winced. Feeling hurt, I changed the subject and asked what films had influenced him as a child, when he began acting in commercials and on television shows like Murder, She Wrote. “I don’t know anything about movies,” Phoenix replied. “I’m not trying to censor myself, but I really don’t know anything.” I then tried to be practical and inquired about audience reaction to the Her screening. “I don’t know, since I didn’t watch the film,” Phoenix countered. “I usually see a rough cut of the movie if the director asks me to, but I won’t see it after that. There’s a danger that watching the movie might cause me to wonder if I was good or bad, and that might mess me up in some way. I don’t want to risk it. Awards shows are excruciating. They show a clip out of context, and I won’t watch. I look at the ground.” Phoenix sighed. “You come up with reasons for doing interviews,” he said finally. “But I don’t think those are the real reasons.” This was a hint, perhaps, that he believed the true motivation for an actor doing press might have less to do with supporting a film than with ego and a desire for attention. “You fucker! You fucker!” Phoenix then said, out of the blue. I must have looked shocked. “I’m sorry,” he said, laughing. “That’s a line from Inherent Vice. I keep saying it.” He laughed again. “I have to go to the bathroom,” he said, standing up. I wasn’t sure he would come back.

Nearly two months later, on a Thursday night, I was at the Greenwich Hotel again, this time to interview Bradley Cooper, who was staying there while in New York for the premiere of American Hustle, in which he plays an ambitious FBI agent. When it comes to promoting his films, Cooper, who is also 39, may be the polar opposite of Phoenix. Cooper is a film lover who thinks like a businessman; he will enthuse about, say, how much he admires The Royal Tenenbaums and how it’s a crime that Wes Anderson, the director, never won an Oscar. What’s more, he doesn’t hesitate to fly to any city anywhere to meet and greet and to present at a premiere or a film festival. He seems to view doing press as a form of campaigning, and it works: Last year he was nominated for an Academy Award for best actor for his part in Silver Linings Playbook, a dark comedy about a love affair between two mentally unstable people. Cooper, who didn’t start acting until after he graduated from Georgetown University, has a kind of puppyish zeal for every aspect of filmmaking. Even though he is quite accomplished and is no longer required to audition, he will make a video of himself to prove to a director that he is right for a part. Cooper is so enthralled by the process of acting that it doesn’t even seem to bother him when directors turn him down. “I read for Scorsese for The Wolf of Wall Street,” Cooper told me. “But the part went to Jonah Hill.” As usual, he sounded upbeat.

In the many months between the release of Silver Linings and the Oscars, Cooper crisscrossed the globe several times to publicize the film. “I loved it all,” he said, plopping down on a velvet couch in the corner of the hotel’s cozy bar. He was wearing jeans and a navy sweater that zipped at the neck and accentuated his bright blue eyes. That afternoon, he had flown in from Hawaii, where he was shooting Cameron Crowe’s latest film, in which he plays a military contractor. “The way I look at it is, I always dreamed of being in the room with actors like Daniel Day-Lewis and Robert De Niro, so how can I mind being there?” Cooper said. “If I’m a kid and my whole fantasy is to be part of this world, and then I’m actually doing it with my heroes, shame on me if I complain about having to do an interview on the red carpet.” He paused and took a sip of mint tea. “Although it is a helluva grind.” Cooper was, perhaps, thinking back to the many, many forced flirtations on the awards circuit when TV entertainment reporters asked him to speak French or dance or dish about his Silver Linings costar, Jennifer Lawrence. Whatever the request, Cooper was a gentleman throughout: He knows the value of media attention. “There were times when I felt like a fucking monkey,” Cooper said now, laughing. “But most of the time, it was amazing! I love Q&A’s. I love talking to people about films. I can do it for hours and hours. And I wanted the film to be seen.”

During the campaign for Silver Linings Playbook, which made more than $236 million internationally at the box office, Cooper, who has an almost fanlike enthusiasm for actors and filmmakers, grew very close to David O. Russell, the film’s writer and director. “Bradley became like my brother,” Russell told me at a party for their latest collaboration, American Hustle, a loose retelling of the ABSCAM sting in the ’70s. “He has a rare ability to think of the whole film and not just his performance. Most actors concentrate on their part, and that’s fantastic, but Bradley can hold the entire movie in his head. I started to ask him what he thought about certain scenes in Silver Linings, and the next thing I knew, I had asked him to be in the editing room.”

Unlike Phoenix, Cooper has no problem watching himself. “I don’t give a fuck about my character—I love storytelling,” Cooper explained. “In the editing room, you have to be vicious. You’re sitting in a cave for 12 hours, and you get the knives out and carve out the story together. But don’t get me wrong, it’s not a selfless thing: If I’m great in a bad movie, it doesn’t matter. But if I’m good in a great movie, then that’s good. All I care about is making the movie great. I’m not precious about my work in the film. Not at all.”

The day before my interview with Phoenix, he was onstage at the Walter Reade Theater in Manhattan with Spike Jonze, who wrote and directed Her, and his three costars, Rooney Mara (who plays Phoenix’s estranged wife), Amy Adams (who plays his best friend), and Olivia Wilde (who plays a woman with whom his character, Theodore, goes on a tumultuous date). The only person missing was Scarlett Johansson, who is the voice of Samantha, the love object–operating system. The film had just received thunderous applause, and Phoenix, dressed in the same jeans-and-sweater ensemble he would wear to our interview, was chewing gum and smiling. He looked amused, as if he were reacting to a private joke. Dennis Lim, the moderator of the event, opened the floor for questions. “Joaquin, what did you think of the script?” someone asked. “I liked it,” he replied tersely. “In the movie, you have a relationship with an invisible girlfriend. Was it hard for you to talk to someone who wasn’t there?” another critic asked. “No. I’m accustomed to walking around my house talking to myself,” Phoenix answered. “So it wasn’t that dissimilar.”

Jonze did his best to keep the conversation moving, but when your star is recalcitrant, it is difficult to continue answering questions earnestly. “Joaquin is an actor, not a politician,” Jonze told me later, calling from his office in Los Angeles. “He does things his own way. Journalists need to put things into words, and Joaquin doesn’t want to. That’s part of the reason he’s such a great actor. He likes to be lost in the part that he’s playing.”

Jonze first became aware of Phoenix in 1995’s To Die For, directed by Gus Van Sant. Phoenix, who was 20 at the time, played a high school student who falls in love with a fame-obsessed small-town TV reporter, played by Nicole Kidman. Under the sway of lust, and to prove his devotion, Phoenix’s character helps murder her husband. “Joaquin was fascinating in the film—you couldn’t take your eyes off him,” Jonze recalled. “And for Her, I needed to find someone with that power, who could physically represent two people—himself and Samantha.” When Jonze finished the script, he gave it to Phoenix first. He drove over to his house, and Joaquin told him it might take him a week or so to read it. It was 10 p.m. When Jonze woke up the next morning, there was a very long text from Phoenix saying he had read Her and that he would play Theodore, assuming the director still wanted him. “I was thrilled!” Jonze said. “What’s important to understand is that Joaquin is the least pretentious person I’ve ever met. He takes his work seriously, but he doesn’t take himself seriously. Sometimes I think that’s why he’s misunderstood.”

Phoenix’s need for authenticity and artistic challenges may stem from his unusual background. His parents went from being believers in a Christian sect called the Children of God to being believers in the careers of their five children. When Joaquin (who was then known as Leaf) was a small child, his mother was a casting agent at NBC; he starred in his first film, SpaceCamp, at 11. Phoenix has been nominated for Academy Awards for his performances as the evil emperor Commodus in Gladiator in 2000; Johnny Cash in Walk the Line in 2005; and Freddie Quell, the devoted, damaged follower in The Master, which came out in 2012.

The Master was a kind of rebirth for Phoenix—he had nearly annihilated his career in 2010, when he and his best friend, Casey Affleck, made I’m Still Here, a hoax documentary in which Phoenix announced to the world that he was going to quit acting and become a rapper. With Affleck directing, they attempted to make a kind of statement about celebrity. The film culminated in a real appearance on The Late Show With David Letterman, where Phoenix, who looked exceptionally overgrown and disoriented, seemed to be losing his mind in front of a live audience.

That turned out to be brilliant acting. “For me and Casey, I’m Still Here is a comedy,” Phoenix told me when we met at the Greenwich. It was one of the few times I had raised a topic that engaged him. “We both like uncomfortable humor. Before we did the film, I had seen the TV show Celebrity Rehab. We were close to getting me on that show. I kind of envied the acting on Celebrity Rehab. I almost did it—we wanted to go all the way.”

For Affleck, who is married to Phoenix’s sister Summer, the project was more complicated than that. “I still run into people now, four years later, and they say, ‘Is Joaquin all right?’ ” Affleck said. “I’m like, Oh, my God! It’s never going to be over. But if nothing else, I learned a lot about acting from watching Joaquin. He was so amazingly committed. There’s no one quite like him—he has no fear.”

Of course, Phoenix would deny that: “I was very afraid and concerned after I’m Still Here,” he said. “I realized that it might be more difficult than I thought to get work again. And I want to act. Casey was truly the bravest person. He had to deal with me saying, ‘Fuck you—I don’t want to finish this movie.’ It’s not like I didn’t want to work again—and I was worried. But then Paul [Thomas Anderson] called me for the part in The Master. And things came together with Spike.”

Phoenix paused. “It’s good sometimes to not be welcomed,” he said, after lighting another cigarette. “If everyone said, ‘Welcome,’ ‘Welcome,’ ‘Welcome,’ it could be dangerous. What I want most is to challenge myself—and I’m lazier than anybody. Wouldn’t you like to just get in the water and float for a very long time? I would. But that’s no good. You have to force yourself to battle, to not float.”

I pushed my luck: “Was it the complications of the role in Her that attracted you?” I asked. Phoenix stared. “When you fall in love with somebody, you can’t really figure out exactly why,” he said in a way that can only be described as kind. “You want to experience life with that person. And that’s what it’s like when you read a great script: You fall in love. I don’t need to know why.”

Like Phoenix—and this may be the one thing they have in common—Cooper has a romantic streak when it comes to acting and movies. He grew up in Philadelphia; was very close to his father, a stockbroker, who died in 2011; and seems to view show business as a large, extended family. After starring as the toxic playboy Phil in The Hangover in 2009, which was a $467 million worldwide blockbuster, Cooper, who was then known for his work in comedies, fought to be seen as a dramatic leading man. In 2011, Relativity Media, an independent studio, financed Limitless, a mix of thriller and intellectual parable that starred Cooper as a writer who discovers a drug that allows him to use 100 percent of his brain power for personal gain. Limitless was a hit, redefining Cooper’s profile in Hollywood. Suddenly he was considered an actor who could guarantee box office returns, and he had range: He could be romantic, funny, charming, threatening. “Careerwise, Limitless changed everything,” Cooper told me. “That film paved the way for someone like David O. Russell to consider me for Silver Linings Playbook and American Hustle.”

Richie Di Maso, the character Cooper plays in American Hustle, has a boyish enthusiasm for both capturing bad guys and disco dancing. “My character was originally very straight,” Cooper explained. “I said, ‘I love you, David, and I’ll do anything for you, but why don’t we make the character fucking amazing? Let’s make him someone we haven’t seen before.’ ”

In March 2013, about a week after the Oscars, American Hustle started shooting in Boston. The timing was good: Despite a huge push from Cooper, Silver Linings Playbook won only one Academy Award (best actress for Jennifer Lawrence), and returning to work was an excellent way for Russell and Cooper to quell their disappointment. “At the time, I was with David 12 hours a day, and I told him I wanted Richie to be different and to look different,” Cooper said. “We tried wigs and that didn’t quite work. One day, we curled my hair. The minute we did that, Richie was born.”

There’s a kinetic energy to Cooper’s performance in American Hustle, a kind of manic intensity that is also true of the actor himself. Unlike Phoenix, Cooper wants to be liked and understood. Phoenix may be the more daring, complex actor, but Cooper has a contagious love of the game. They share a deep respect for great directors, but while Phoenix has an almost mystical relationship to his craft, Cooper is proactive: He writes letters to people like David Fincher, whom he longs to work with, and he options books, including the one for his next project, American Sniper, in which he’ll play Chris Kyle, a soldier who served in Iraq. “Clint Eastwood is directing that movie,” Cooper said as he prepared to leave for dinner. “I’ve tried to work with Clint since Flags of Our Fathers. I put myself on tape for that, and also to be in Gran Torino, and again, to play Leo’s [Leonardo DiCaprio] boyfriend in J. Edgar. Nothing worked out. And yet, when I was an adolescent, I believed in two things: I was going to work with Robert De Niro, and I was going to work with Clint Eastwood.” Cooper paused. “Now De Niro is like a father to me, and I’m making a film with Eastwood! My life is a real dream. Sometimes I get afraid that I’m going to wake up. And then I realize, if I work hard, good things will come.”

Photos: The Agony and the Ecstasy

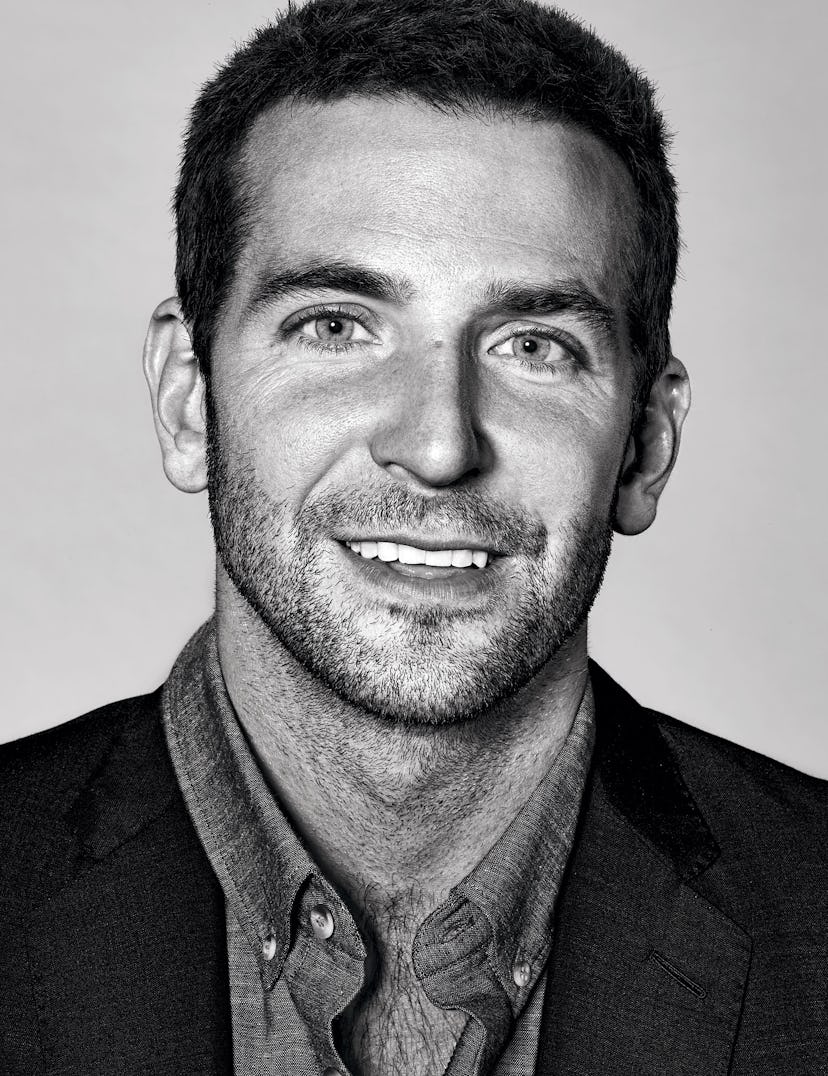

Bradley Cooper.

Tom Ford Blazer; A.P.C. shirt.

Joaquin Phoenix.