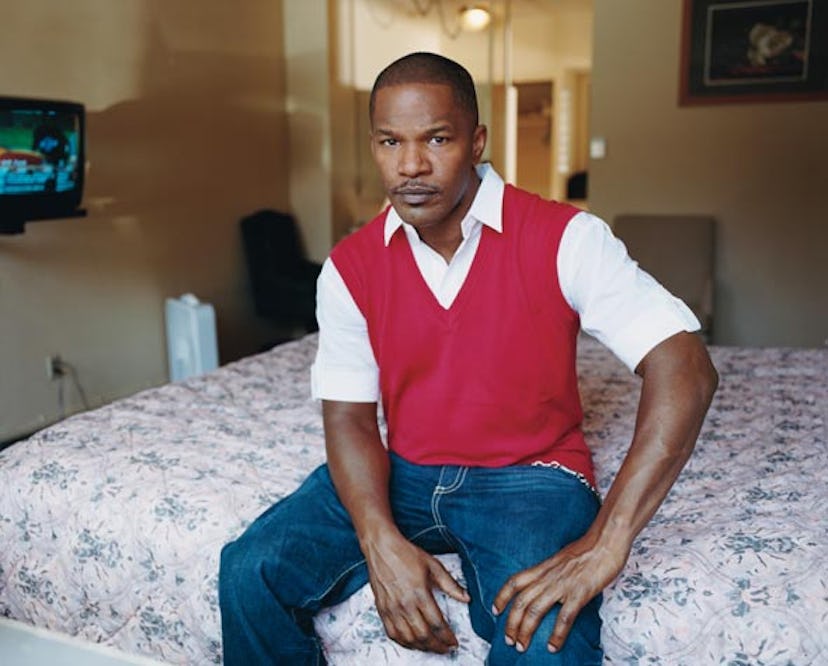

Jamie Foxx

The Chameleonic Oscar winner gives a whole new meaning to role-playing, both onscreen and off.

In the Nineties, when he first broke onto the national scene, Jamie Foxx was a quirky and outrageous sketch comic, playing characters like Ugly Wanda, a deeply unappealing woman who would vamp around the stage of the variety TV show In Living Color. In 2004 he took on the guise of Ray Charles—an Oscar-winning turn for which he embodied the musician not just onscreen but also at the Grammys and in other public appearances. Since then, he’s also taken the shape of a hip-hop star, dancing on MTV alongside scantily clad models and Kanye West. And in magazine profiles and gossip columns, he routinely plays the role of a blinged-out Hollywood playboy, holding court among double-digit entourages in clubs and hotel bars around the world.

Waiting in the conference room of Foxx’s production offices, looking out over the trees of Beverly Hills, I can’t help wondering which Jamie Foxx will show up today. But the Foxx who enters is none of these characters. He wears a serious expression and an outfit that makes him look like he just finished some handiwork around the house: jeans splattered with paint and two layered V-neck T-shirts. There’s not a single carat of jewelry on him, though an indentation on his left earlobe is evidence of a frequently worn large diamond stud. Is this the real Jamie Foxx?

The question of whether the 40-year-old might be suffering from a case of multiple personality disorder is apropos: In his latest movie, The Soloist, Foxx plays Nathaniel Ayers, a gifted classical musician whose schizophrenia takes him from Juilliard to L.A.’s skid row. Directed by Joe Wright (Atonement, Pride and Prejudice) and based on a true story, the film follows the friendship between Ayers and Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez (played by Robert Downey Jr.), who wrote about Ayers in the newspaper and in a book published this past April.

For The Soloist, Foxx immersed himself in Ayers, as he does with all his subjects. When Lopez, Ayers and the filmmakers attended a concert at Walt Disney Hall, which sits blocks away from the skid row streets where Ayers once lived, Foxx quietly trailed Ayers with a digital recorder. He met with doctors to learn about schizophrenia, and he trained for months to learn how to play Ayers’s instruments of choice, the cello and the violin. “He also lost a lot of weight, shaved his eyebrows and had his teeth ground down,” says Wright. “It wasn’t a Method way of doing it, it was really getting under the skin of the character.” When Foxx is playing Ayers, says Lopez, “it’s really eerie—you have to look twice” to make sure it’s not the real thing.

Robert Downey Jr. (at left) and Foxx in a scene from The Soloist.

During downtime on the set, however, Foxx was mercurial, as always. Downey recalls that on some days Foxx could be found “in this kind of recital room in Disney Hall, probably with 20 or 30 extras, improvising on the piano. If Jamie Foxx feels like it’s time to hold court, boy, he can give people what they want. Other times he might not say a word all damn day. Somewhere in his overall makeup,” Downey adds, “there’s someone who’s always taking the temperature of the room, like mentally licking his finger and holding it up.”

Foxx grew up in Terrell, Texas, a tiny town near Dallas. He was raised by his grandmother, who adopted him and made sure he went to church and practiced the piano every day. The musical training would eventually earn him a scholarship to the U.S. International University in San Diego, where Foxx first gave stand-up comedy a go. He attracted a following with his impressions of celebrities like Mike Tyson, Bill Cosby and Prince, and in 1991 he landed a part on In Living Color. The fame he found on the show opened more doors: He released his first R&B album in 1994, and in 1996 he got his own sitcom, The Jamie Foxx Show. After a string of forgettable comedy films, he turned to dramatic acting, first as a football player in Oliver Stone’s Any Given Sunday and then alongside Will Smith in Ali and Tom Cruise in Collateral, both directed by Michael Mann. Lately he’s also become a reality-television producer, with the current MTV series From G’s to Gents, in which thugs are trained in fine living by Sean Combs’s former personal assistant, Fonzworth Bentley. And he recently formulated his own Sirius satellite radio channel, The Foxxhole, which broadcasts comedy and talk shows 24 hours a day.

But for all his ability to shape-shift, Foxx has remained something of a Hollywood outsider—ever the observer perched on the fringes. The role of arrogant party boy is certainly in his repertoire, but on the night he won his Oscar, he skipped the obligatory Vanity Fair bash to attend a celebration his friends and family threw for him. And when Foxx talks about costars and movie industry colleagues, he takes the tone of an ordinary civilian recounting fleeting encounters with celebrities at restaurants or airports, laying them out like souvenirs in an otherwise quotidian life.

There was the time Keenen Ivory Wayans told him, “As an African-American in this business, if you’re not a hundred percent hot, you’re nothing.” And the time Smith, after Foxx became successful, pulled him aside to say, “Go home. Quit partying so much. Go focus on your work.” He recalls when Oprah Winfrey took him to meet Sidney Poitier, who said (Foxx relays the story in a dead-on impersonation of the venerable actor), “I’m going to give you something: responsibility.” More recently there was Clint Eastwood, whom Foxx found himself sitting next to at a function; Eastwood admitted that he still gets nervous when he makes a movie. And there was Paul Anka, the music legend, who said Foxx’s goal should be to work only when he wants to: “Jamie, you want to live life on your own terms.”

If today’s low-key demeanor is worth reading into, it seems the real Jamie Foxx is not the larger-than-life extrovert his public persona often suggests. There’s a difference, he says, between being in Hollywood and being of it. “I love being in Hollywood,” he explains. “There are going to be great moments: great parties, great movies, great projects that you’re a part of. But I also love the fact that I can step outside of it.” Foxx doesn’t reside in a chichi L.A. enclave, but rather out in the Valley—for years he lived in Tarzana (where he frequently could be spotted at a local bowling alley), and in the summer of 2007 he bought a 10-bedroom Mediterranean villa near Thousand Oaks. Currently single, he shares the house with his two sisters and an ex-husband of his mother’s whom he considers his stepfather (Foxx’s mother lives in Texas). His 14-year-old daughter and her mother (with whom Foxx is no longer romantically involved) live nearby. “There’s nothing wrong with becoming part of the scene,” Foxx says, “but just to keep your own thing, to keep your Texas swagger and your friends and family who aren’t affected by the scene around you—for me, that keeps me breathing.”

Right now Foxx is focused on putting together his follow-up album to 2005’s Unpredictable, which went double platinum. As for his next film, Foxx says he’s interested in playing Mike Tyson. He’s confident he could pull off the role: For Redemption, a TV movie based on ex–gang member Stan “Tookie” Williams, Foxx bulked up to 225 pounds. “Mike Tyson fought at 216,” he says. I mention that about a year ago I saw Tyson and his entourage get thrown out of a Hollywood nightclub after they sat down at a booth that wasn’t reserved for him. Foxx says that’s one of the reasons he’s so interested in Tyson: “There used to be a day when it didn’t matter if [a booth] was reserved for the president; he would sit there. Now he gets thrown out. It’s what the American dream and nightmare is all about: It’s the dream and then all of a sudden—” Foxx snaps his fingers.

“You always have the fear that maybe one day they’re going to say, ‘We don’t need you. We don’t like you,’” he says. “But one thing that I have on my side is that I can tell a good joke. If things went bad, I would be in Vegas or somewhere, still performing—I’d still have my light on.”

Or else he’d be in Vegas developing properties. He mentions another piece of advice he’s received, this one from the Maloof brothers, whose sprawling business empire includes the Palms Casino in Las Vegas and the Sacramento Kings NBA franchise: “You want to be able to have things working for you.” So Foxx has recently been looking to invest in real estate. “When I get to 50,” he says, “I want to be able to say, Okay, I don’t have to work. Things are working for me.”

It seems Foxx can be all these things—hip-hop force, Oscar winner, comedian, budding business tycoon—as long as he’s allowed to compartmentalize, to immerse himself in one role at a time. “It’s like eating your food. I don’t know about you, but I eat one thing on my plate at a time. I eat my macaroni and cheese, then I eat my green beans, then I eat my steak,” he says, a bit of extra Texas twang creeping into his voice. “It’s about making sure that everything you do is a hundred percent and then moving on to the next thing.”

Photos: The Soloist: Francois Duhamel/Dreamworks LLC and Universal Studios