Jake Gyllenhaal On Masculinity, Fatherhood, and Death

“You can sit there. I’m giving you the nice view,” Jake Gyllenhaal told me on a recent afternoon—not that there was a bad view to be had. He was gesturing at a chair facing the lush backyard of the Beyoncé-beloved pizza restaurant Lucali, which that day seemed like the only patch of Brooklyn where the only sound was the chirping of birds. “Through the years of doing [press] junkets and things like that, I’ve always thought it’s so much nicer for everybody when you can actually engage with someone, instead of just sitting in a hotel room,” Gyllenhaal explained of his choice of venue to discuss his second campaign for Calvin Klein. Plus, “everyone’s happy when pizza’s around,” he added with a laugh.

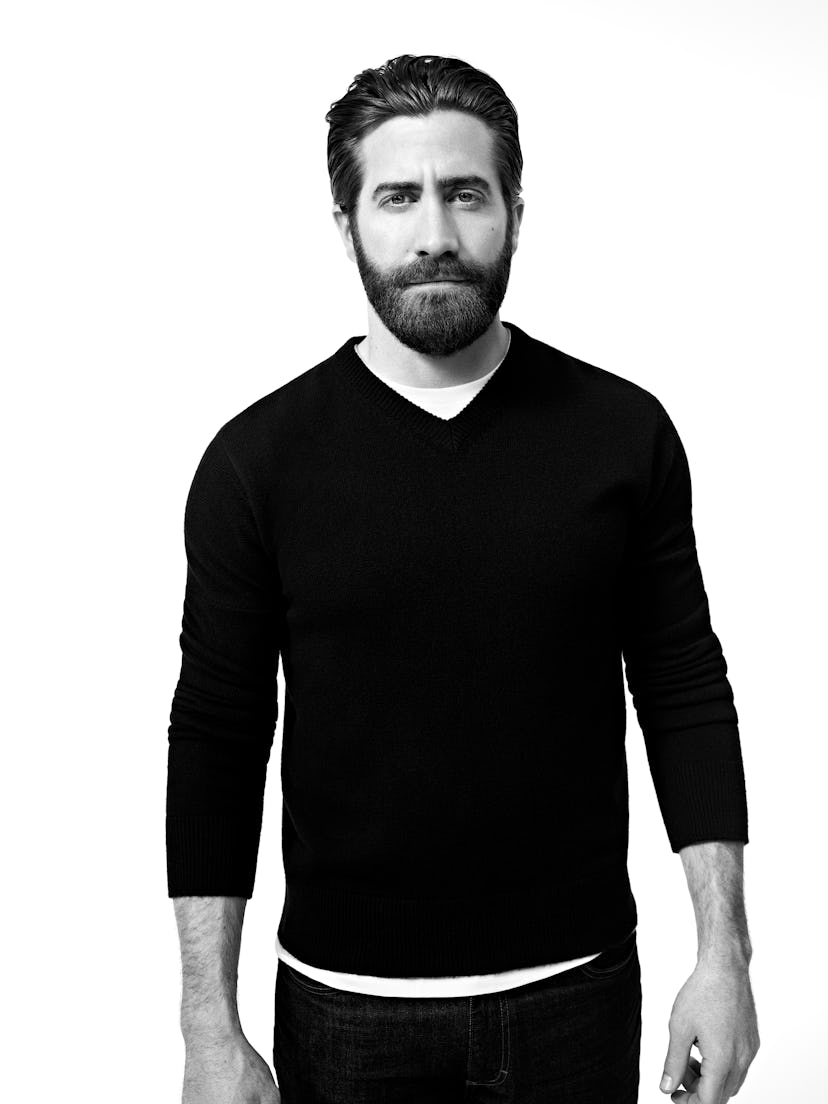

This time around, Gyllenhaal is the face of the brand’s new Eternity eau de parfum for men. The fragrance—now a bit fresher and more sensual than usual, thanks to hints of suede, sage, and cypress—launched this week, in the midst of Gyllenhaal’s return to Broadway with the play Sea Wall / A Life. As is often the case with the actor’s projects, both are deeper than one first might expect; the former is actually a meditation on masculinity, and the latter on life and death. Read on for his thoughts on all of the above, here.

Raf Simons was a large part of why you started working with Calvin Klein in the first place, but you’re obviously still working with them now, after he’s left. What is it about Calvin Klein that draws you to the brand? What I always loved about it even before Raf, is the idea of the art of simplicity—how hard it is achieve, and how essentially American it is. And because of that, it’s inclusive in the international community; it’s like the America that I want to be living in. I think that’s also why it attracts a lot of different artists, because even a t-shirt can be distinctive. You get to be yourself. I’ve been offered a lot of different things like this, but none of them felt genuine and authentic to me. And Calvin Klein allowed me to do something creatively. Eternity is about family, and originally the idea for the campaign was a love story, which leads to getting married. And I was like, how do we then evolve that into an idea? If there’s a love story, what happens after the love story?

Well… [Laughs.] Yeah, yeah. Yes, the fragrances are usually sold through sex, and that’s a big part of it, like romance and stuff. But with romance and sex usually comes a baby, yes? I mean, not always. But that would be an interesting idea, and why not?

So you basically pitched it to them—the idea of making it about family? Yeah. And then to Carrie, obviously—the baby.

Did you have any input into this men’s campaign, too? In a lot of ways, it’s an evolution of the same campaign and the same ideas. But it’s also about how I think that Eternity has a real femininity to it, and a really strong masculine sense. It smells sort of woody. All of our definitions about masculine and feminine are all evolving, so I just like the idea of separating from a particular classic fragrance, and there being a feminine side as well. And it doesn’t necessarily have to be only for a man. I really like that idea, particularly as the definitions of masculinity are in transition.

According to Calvin Klein, this new version of Eternity “captures the spirit of today’s man.” What does that mean to you? I have no idea what that means, so that’s the first step. [Laughs.] But I think that’s a big part of it. I think the sort of foolish nature of saying that you know what a man is supposed to be has been a problem. I think that a big part of the modern man is listening, though I also sometimes find that it’s the hardest thing to do, particularly in a culture that has been, up to this point, male-dominated. So if listening is a big part of the modern man, it’s hard for me to tell you what I think a modern man should be. I just think it’s being pieced together slowly, you know? And it’s changing. There’s a whole new generation that is defining all new things. There’s this amazing psychoanalyst-slash-philosopher named Robert Johnson who wrote three different books—one called She, one called He, one called We. He really goes into essentially how we have the masculine persona, the feminine persona—all those things—in us, and how we balance them. The people who I admire, they embrace and respect all sides of themselves—the masculine, the feminine, and the combination of the two.

Who are some of those people? I would actually say Tom Holland, who I worked with [on Spider-Man], is really one of those people. There are so many stigmas that he just embraces—like, he’s this beautiful dancer, and he’s also Spider-Man. He’s incredibly sensitive, but he’s a bad ass. He’s strong in that way, and strong in a different way. In that way, I’d also say Frank Ocean. It doesn’t just have to do with sexuality. I think it has to do with expression. There’s a certain kind of courage in expressing someone’s individuality, and I like people who do so in a way that feels really true. And then there’s someone like Greta Thunberg, right? There are also kids that are amazing individuals. My nieces amaze me, because they’re of a whole other generation with a whole different perspective.

It’s not necessarily about age, then, for you. I think when someone is true, and someone is kind, and someone is humble. I think of people who can sort of speak the truth. Some people speak the truth just through their expression, some people actually say it through their person. And there are all kinds of people who do it. I think of Kendrick Lamar. I think of Jay-Z, who I think has evolved closer and closer to the truth as he’s evolved his career. And if the truth is his admitting things now—it doesn’t have to be about what hip-hop has always been about. It can move; it can change. It can be about love. I think J. Cole is incredible in what he says in his lyrics. There’s an incredible verse in that song with I don’t even know how to pronounce—six lack [6lack], or whatever? [Laughs.]

I think it’s just pronounced “black.” Yeah, him. [Laughs.] He does an incredible verse in this song “Pretty Little Fears.” And to me, that verse is pretty much the embodiment of the kind of man that I admire.

How has your own definition of masculinity changed over time? I’m constantly trying to figure it out. A lot of it has been defined by the incredible women in my life, and my wonderful dad who’s always embraced me—my sensitivities, my heart. He never really tried to push me to be something other than I am or was. He pushed me in places that he knew would help me learn.

Did you ever feel pressured to suppress your emotions, or express any of the more conventional—and toxic—aspects of being a man? Well… for me, that was hard. [Laughs.] You try and be what, you know, your idea of a “tough guy” is, but for me, it never really worked out well. Thank god I had family around me who were so smart and strong and cool and would call me out on so many different things, too. But I think the more clichéd idea of what a man is is something I try to explore those ideas through the roles I play. If I think about acting, I played a boxer, I played an officer, I played someone in the military, and there’s this sort of sense of a more classic idea of “male.” They ask questions like what do we fight for? What do we care about? I think that those things are very important, and that they’re being lost. And they help lead me towards something else.

You were a dad in your last Calvin campaign, and you’re also a dad in Sea Wall / A Life, your new Broadway play. In fact, you talk pretty often about wanting to be a dad. Is that something you’ve been exploring through your work on purpose—and something you’ve actually been thinking about making happen, too? Yeah, of course. I mean, that’s like—yes. All the things I’ve done in my work have always been questions to myself. Going back to what it is to be a man, that was true even in Tom Ford’s movie [Nocturnal Animals]. I played a character who was like a deer in the headlights, who didn’t exhibit any of those classic Hollywood leading man actions of like defending one’s family or fighting for something, and then gets taken advantage of. Those types of things, like that kind of a response to a tragedy, are interesting to me. What would I do in that situation?

So when it comes to family: Yeah! I think that obviously doing a commercial about and trying to tell a story about and evolving the overall piece about this fragrance into the idea of a family was me asking myself those questions—questions about my desire for what that is and wanting to have a family of my own. All of those things are absolutely at play in being a part of all of this. I do often talk about acting as wish fulfillment, and then ultimately Fuck wish fulfillment—can you make things real? Like, before I did Brokeback Mountain, I remember I was working with a beautiful acting coach and she said to me, ‘You don’t have a lot of relationships with animals. You should get yourself a dog.’ So my I got my first dog, besides my family’s dog, a year before I started that movie, and I’ve had dogs ever since. And I know that sounds a little flip, but there was something where I was like, Oh right, you don’t know until you devote your life to another sentient being like that. And I think the same thing is at play always. There’s a merging of reality and fiction in what I do. I don’t love to wear masks, you know? I like to explore the unknown—the things I’m scared of and fascinated by. And the things I want to do in real life, eventually.

Well, it sounds like death made its way onto that list—it seems to be at the center of Sea Wall / A Life. I think I’m going to die some day, yes. I think I’m going to die.

I think so, too. I’m sorry. Interview’s over. [Laughs.] No, I know.

Well, I know that you do a lot of research before you commit yourself to a project. This time, did it end up changing your thoughts on what happens when we die? Yes. I’ve done three shows with Nick Payne, who wrote my monologue [in the play]. One of them was about love, life and death, losing the people we love, the cosmos, the relativity of time—all of those things—so we met with death doulas and neuroscientists and so many amazing different people in production. I really do believe that I don’t want to be afraid of [dying]—though I probably will be, in so many ways. But I really feel like meditating on that idea is the only way that you can be present in whatever it is that you’re doing. Through the whole winter, and before that, even, I’ve done research not only on that, but on the process of birth, because the whole piece is really about birth and death and transition. Not just literally—it’s also the things that die in us and the things that are born in us and their evolution. One of the last lines of the show is “and again, and again, and again.” And we do that—we do it again, and again, and again. We evolve.

So it didn’t get too dark to think about? Oh, no—I mean, it’s such a beautiful thing. The show’s about the in-between—those moments when someone you love has come into the world, and you don’t know how much you will learn to love them and they will be almost everything to you. And sometimes when those people that you love, you lose, whether it be they lose their life or you move out of a relationship or you move into a new—whatever it might be. It’s about the way the light changes in those times. I’m sorry to be pretentious, but Emily Dickinson has this line “There’s a certain slant of light, winter afternoons.” A lot of the show is about light and how it changes as we experience transitions. To me, I felt nothing but love, which is why I want to continue to do it. I’ve never had such a response from the audience before, and I’ve never had such an incredible experience. Not in anything I’ve ever done.

Besides research, is there anything else you do to prepare for being on Broadway? I did a musical, and it was a ton of preparation, like skills I had to learn that I had never cultivated and techniques and things for your voice and sustenance and endurance for the long run. And I do employ those things in this show. But this show is more about breaking those things and taking those things out. I try to stay as present, so there’s no sense of boundary or preparation when I walk out onto the stage. It’s just me coming out, and I don’t know where you guys are going to take me. That’s my favorite, and that’s why it’s incredible. It’s like, where do you guys want to go tonight? I have no control over this car. You tell me where you want to go and I’ll drive there.

Related: Jake Gyllenhaal and Sister Maggie Were “Traumatized” By Their Homemade Halloween Costumes Growing Up