Dr. Ivo

The world’s most famous plastic surgeon offers a tour of his fabled clinic in Rio and his lush private island, his inner sanctum.

Ivo Pitanguy is famous throughout the world, but in his native Brazil he’s a legend, eclipsed in public recognition only by Pelé, the soccer god. That a plastic surgeon could reach this level of renown says something about the Brazilian worship of physical beauty and, of course, Pitanguy’s knack with the knife, for which he’s been dubbed “the Michelangelo of the scalpel.” But the doctor clearly possesses other, more subtle qualities as well. “Pitanguiser,” a word coined in the local Portuguese dialect, translates as “human charisma, intelligence and compassion.” In our harshly clinical Nip/Tuck culture, Pitanguy has said he sees his business as “the search for harmony between body and soul.”

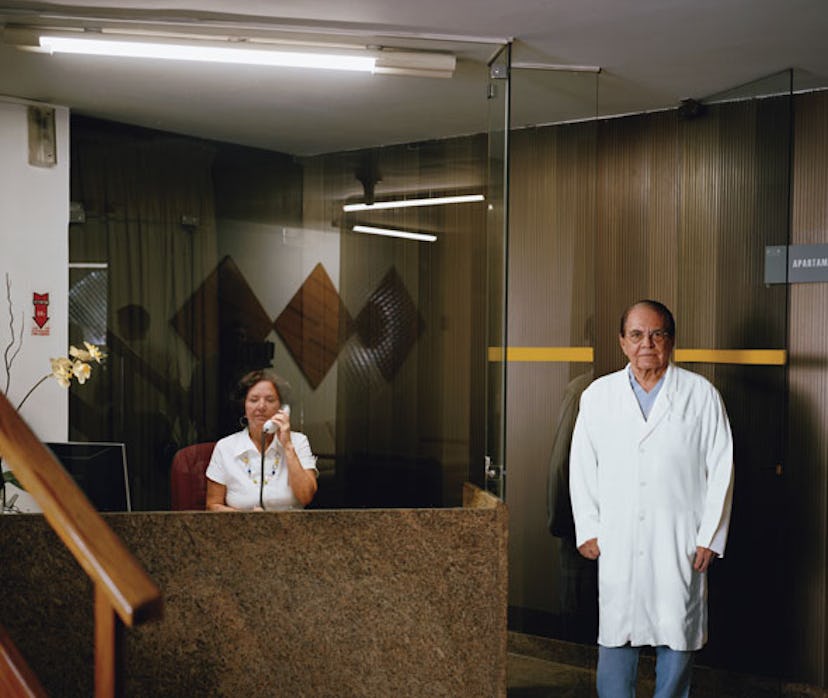

At 82, Pitanguy still presides over a 70-person staff at the Clínica Ivo Pitanguy in Rio de Janeiro. Since 1963 kings, queens, presidents, movie stars and socialites have flocked to its fabled but discreet doors in search of rejuvenation. Beautifying the rich and famous has made Pitunguy rich as well: In addition to his leafy estate in Rio, there is a chalet in Gstaad, an apartment in Paris and a private island 100 miles from Rio, which he bought in the early Seventies. Ever since, an invitation to visit this inner sanctum has been considered a hot ticket—one generally offered only to family, close friends and select patients who are allowed to “rest” after procedures.

Happily for W, however, the doctor agreed to a visit, which begins at the heliport in Lagoa, a lush enclave of Rio. After lifting off beside an inland lagoon, the chopper soars past the outstretched arms of Jesus—the famous colossal statue of Cristo Redentor that sits atop Corcovado peak. Black rain clouds are gathering, but the pilot decides to do a 360 around Jesus, whose hands we can almost touch (and which we will need if this storm breaks, I’m thinking). After sweeping low over the delirious beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema, we fly southwest over emerald- colored mountains and on toward the brilliant blue Angra dos Reis, the Bay of Kings. Among the hundreds of islands that dot the bay is Pitanguy’s Ilha dos Porcos Grande—Big Pigs’ Island—which, notwithstanding its rustic name, is a graceful curved landmass about a mile long.

As the aircraft lands at the end of a long dock, next to which Pitanguy’s large, gleaming yacht is anchored, white-shirted houseboys scurry to meet it. Pitanguy is waiting on a terrace next to an open-air stone pavilion, where lunch is being prepared by more servants. An elegant, compact man, he has a kindly face that projects curiosity. Joining him is his son Helcius, 46, and Helcius’s Italian-born wife, Beatrice, as well as another Italian woman who is wearing large black sunglasses and is clearly “resting” after being treated by “the Maestro,” as she calls Pitanguy, in Rio. (The doctor’s wife of more than 50 years, Marilu, is in Gstaad, while two more sons and a daughter remain in Rio.)

Following several rounds of caipirinhas, a delicious lunch of grilled fish is served, along with a fine white Bordeaux. Flush with the convivial atmosphere, I press for stories of Pitanguy’s celebrated patients. The roster of luminaries rumored to have employed his services is long and diverse, ranging from the Duchess of Windsor, François Mitterand and the kings of Morocco and Jordan to Joan Crawford, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Brigitte Bardot. But Pitanguy refuses even to confirm a well-known story about late socialite Sao Schlumberger. It is said that she disobeyed his orders to remain in Rio for several days after her procedure and that, as a result, her stitches began to pop open on the plane back to Paris. Pitanguy does, however, volunteer one blind item from several years ago about a prominent New York lady, whom he describes as “a big, tall, strong girl.” Following her facelift, she checked in to one of the suites at the clinic. But carried away by the spirit of Carnaval, which was going on at the time, she procured a feathered mask and went out into the night, where she met a handsome stranger. Soon enough, in the throes of passion, he pulled her hair, with unfortunate results for the stitches at her hairline. “The whole thing came down,” recounts Pitanguy, referring to the skin on her forehead. “He was so traumatized he fainted, and she had to bring him to the clinic.” The lady, Pitanguy adds, unable to conceal his laughter, was just fine.

After lunch, Pitanguy leads a tour of the island. “She called to me like a siren,” he remembers of his first encounter with the place in the early Seventies, when it was an uninhabited wilderness. After purchasing the land in 1973, he reshaped the terrain, creating a series of gently rolling hills, building service roads and installing an electrical generator and other utilities. With well-known Brazilian architect Paulo Coelho, he designed about a dozen small bungalows, which are nestled discreetly in the landscape.

Strolling through the meadows or on the pathways that connect the bungalows, you never know what is going to fly or scurry past you. Pitanguy has assembled a collection of rare animals and exotic birds—saffron finches, rufous-bellied thrushes, green-winged saltators, capuchin monkeys and numerous others species—most of which wander free.

Although he is loath to name names, the doctor is happy to talk about how his profession has changed in the half century since he began practicing. “Today, we all talk a lot about self-esteem, but 50 years ago that was not very common,” he says, taking a seat on a terrace outside his personal bungalow. Growing up in the mountainous state of Minas Gerais, in southeastern Brazil, where his father was a surgeon, Pitanguy saw many accident victims and patients with genetic deformities. They were treated, their bones were reset and they were sent home, with little regard for how the disfigurement would affect the patient’s psyche, he recalls.

Abetted by his father, he added three years to his age and was admitted to the local medical school at 15. After a residency in Rio, he traveled abroad to further his studies, completing a fellowship at Bethesda Hospital in Cincinnati, and then studying with leading surgeons in London and Paris. In those post-WWII years, the field of plastic surgery was developing rapidly. “If you look at the history of plastic surgery,” he notes, “it always goes with trauma, with destruction comes reconstruction.” In the course of his work, Pitanguy realized that the techniques used in reconstructive operations could be used for purely aesthetic purposes as well—not a common idea at the time. He decided to make it his life’s work to erase the distinction between the two. Patients in both instances, he believes, are in pain, and if that pain stems from dissatisfaction with the appearance of one’s nose or chin it is no less real. “To be happy with yourself is by no means a superficial desire,” he insists. “My operations are not just for my patients’ bodies. They are for their souls.”

Pitanguy returned to Rio in 1952. After serving as head of plastic surgery at the city’s oldest hospital, Santa Casa, for six years, he founded a teaching program at Pontifical Catholic University that soon became one of the most influential in the field. More than 500 doctors from 40 countries have since received degrees there. Top New York plastic surgeon Gerald Imber, who met Pitanguy at a scientific gathering 25 years ago, describes the doctor as “perhaps the most significant cosmetic surgeon of the second half of the 20th century” and “an inspiration” to the current generation of plastic surgeons.

Pitanguy takes a heavily psychoanalytic view of plastic surgery, to the extent that, he says, “I have always worked like a psychologist with a knife.” Before he agrees to perform an operation (Pitanguy still wields his scalpel, but usually with a team of doctors), he has a conference with the prospective patient to make sure his or her expectations are grounded in reality. “The way that you see your image may not be the way that I or others see it,” he says. “Many people have dysmorphia; they see themselves as much worse than they really are. Many people sublimate problems that are inside them and project them onto, say, their nose.”

In many cases, Pitanguy arranges for the patient to meet with his daughter, Gisela, 49, who is the director of the clinic and a psychotherapist. In some cases, following counseling, patients realize that surgery is not an answer to their problems. One gentleman, Pitanguy recalls, came to the clinic extremely unhappy with his face, which Pitanguy thought was fine. The problem, it eventually became clear, was that the man very closely resembled his father, for whom he harbored a deep, but theretofore repressed, hatred. “When he realized this, he was cured and didn’t have to be operated on,” says Pitanguy.

Most neuroses, he adds, are much more subtle and harder to detect, especially in patients who start with one small procedure, then have another and another. “People want to be perfect,” Pitanguy says, sighing. “In a healthy form, that means taking care of yourself, following a proper diet. But when they want perfection to an extreme, that’s impossible. This form of narcissism becomes self-destructive, pathological.”

But when it comes to unhappiness about aging, Pitanguy is quite sympathetic. “A lot of things can be done,” he says. “I believe that you should correct the [aging] process with elegance and distinction. You should not overdo, because if you overdo, you are only creating a mask without expression, a mask of death. That should be avoided. I try to bring naturalness.” Getting older, he notes, is often most difficult for beautiful women. “They don’t feel it is natural to age,” he says. “But if you help them with a distinguished proper operation, they will be much happier.” As for himself, Pitanguy insists he’s never had cosmetic surgery and doesn’t plan to. “I have a tolerant ego,” he says. “As long as you can tolerate yourself, you don’t need a surgeon.”

While the doctor’s private clinic caters to the elite, he also takes an interest in those at the other end of the spectrum. In 1960 he opened a charity wing at Santa Casa, which he still oversees. Every week, Pitanguy and his team perform free reconstructive surgeries on impoverished patients who suffer from birth defects or have been deformed by accidents. The team also performs cosmetic operations—from calf implants to breast augmentations—at low cost for middle-class people who could not otherwise afford them. In Rio, where the sun shines about 300 days a year and people practically live on the beach, such operations are viewed almost as necessities. Indeed, the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgeons—the largest such association outside the U.S.—performed about 616,287 operations in 2004, the last year for which statistics are available.

No doubt this accounts for Pitanguy’s über fame in Brazil. In 1999 he received perhaps the ultimate accolade—he was the guest of honor of one of Rio’s most important samba schools in its entry to that year’s Carnaval. Riding atop its final dazzling float, Pitanguy served as the personification of beauty, the theme of the event. “This touched me a lot,” he say. “It was an homage paid to me by simple people.”

Simple isn’t the word for most of Pitanguy’s private patients, of course. When asked about the protocol of operating on a head of state or other such potentate, he quotes a scene from Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, in which the Roman leader visits his doctor, Hermogenes, and confides, “How difficult it is to be an emperor in the face of his doctor.”

“A president, king or queen…they are very timid when they are in front of me. These are people who have power and know how to use it. But when they are in my hands, they give the power to me, because they know I can help them,” he says, and then launches into an anecdote to prove his point. Some years ago the chief of one of Brazil’s indigenous tribes came to see him. “He said to me, ‘I feel I am losing my authority because I am getting old,’” the doctor recalls. After a facelift, the shaman returned to the Amazon greatly refreshed and in full possession of his power. He later told Pitanguy that some of his people asked what medicine he took to regain his youthfulness. “It’s a secret!” he replied.

While there’s no medicine, of course, that can approximate the effects of a facelift, patients at Pitanguy’s clinic have long had the benefit of bespoke creams and ointments created to help with recovery and maintenance. After rebuffing many offers, Pitanguy recently agreed to develop a similar line for consumers. Marshalling the clinic’s team of biologists, pharmacologists and aestheticians, he created PreVious, a collection of facial products, and a new body-care line, which are reported to be selling briskly at Bergdorf Goodman and Neiman Marcus to devoted customers.

Still, Pitanguy is quick to note that true beauty is not found in a jar. “The concept of beauty that I feel has been imposed on people in recent years is all about marketing products, selling things,” he says, as a flock of brilliantly feathered macaws strolls past his feet. “But to me, beauty is well-being. Today we are more focused on the superficial, and when people who just live for looks lose them, they will be unhappy. It’s a great mistake not to cultivate the brain and the spirit.” But it certainly helps to have an appointment with Dr. Pitanguy.

Sedaris: Karen Robinson/Retna Ltd.; book cover: courtesy of Little, Brown and Company.