Stay a While

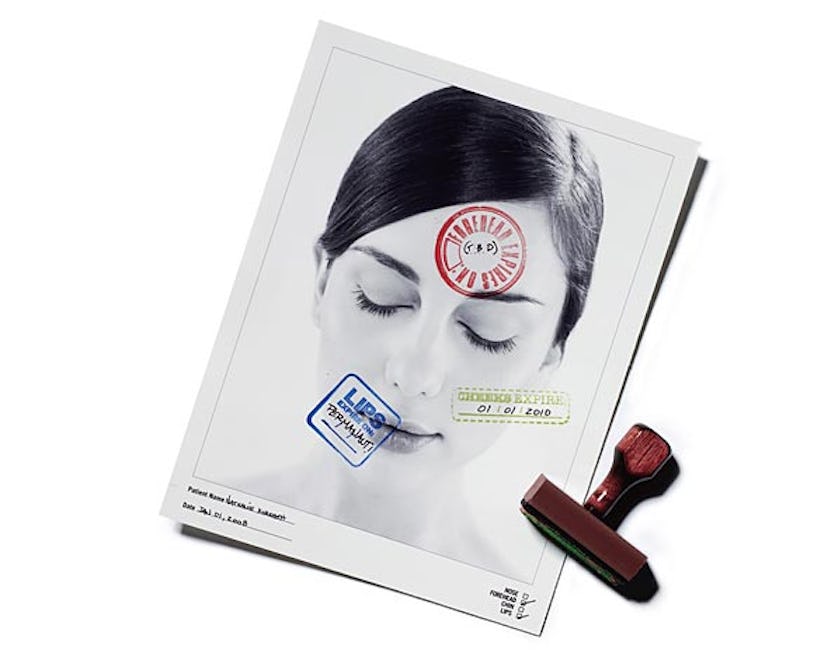

It’s easy to forget, in this age of Botox parties and lunchtime Restylane, that injecting one’s way to a youthful visage is not exactly a walk in the park. True, a few syringes can iron out forehead creases, fill frown lines and deliver a schoolgirl-plump pout, but servicing a whole face can cost thousands of dollars per visit, is not exactly painless, and often results in the sort of telltale bruising and swelling that makes one want to grab a ski mask. The worst part? Results disappear faster than a bag of M&Ms at a 4 p.m. meeting—or at least it feels that way. Every three to six months, it’s time to head back to the doctor for another fix.

Not surprisingly—given the profit potential—the med-tech industry has been working overtime to create a new class of no-operating-room-required procedures that promise more enduring, even permanent, improvements. But while some doctors are excited about these advances, others worry about the downturn in business that might occur if patients are compelled to visit them less frequently. They also caution that longer-lasting results can mean longer-lasting complications.

Still, that hasn’t stopped the buzz surrounding ArteFill, the first filler shown to last at least five years. “We’ve trained 650 physicians since February, when we first began shipping the product to doctors,” enthuses Diane Goostree, president and CEO of Artes Medical, the makers of ArteFill. Approved by the FDA in October 2006, the injectable is composed of microspheres—made from the same material used to produce dentures and Plexiglas—suspended in bovine collagen and lidocaine, an anesthetic. Once injected into the deep dermis, the bovine collagen is eventually replaced by human collagen that the body produces to protect itself from the microspheres, just as an oyster produces nacre around foreign matter, forming a pearl. While ArteFill is especially effective for nasolabial folds and deep wrinkles (one to two treatments are often needed to achieve full results), doctors are also interested in using it for acne scars and cleft lips. “There are ways you can use it that don’t make sense for temporary fillers,” Goostree says, adding that though the company has clinical data to support only a five-year life span, she believes that Artefill stays in place indefinitely. “Pictures of patients in Europe show that even at 10 years, the microspheres are still present.”

While ArteFill is FDA-approved for use on nasolabial folds, Sculptra, another long-lasting filler, is currently indicated only for restoring volume to the sunken faces of HIV patients. Still, doctors, many of whom use the product off-label, are enthusiastic about its ability to plump those suffering merely from natural aging. Jennifer Linder, a dermatologist in Scottsdale, Arizona, compares Sculptra to a “liquid facelift,” perfect for rounding out temples, cheek hollows and under-eye areas. “The natural course of aging is fairly similar to the [fat loss] that’s induced by the antiretroviral HIV medication,” says Linder, who serves as a paid educator for Dermik Laboratories, the makers of Sculptra, teaching fellow doctors how to properly use the filler. Two to four treatments of Sculptra are typically needed to gradually build volume that lasts up to two years.

A third collagen-stimulating filler, Radiesse, is also approved for use with HIV patients, as well as for deep folds around the mouth. It contains microspheres suspended in a water-based gel and lasts for at least a year. Miami and New York dermatologist Fredric Brandt, who is a big fan of fillers like Restylane, Perlane and Juvéderm—all of which use hyaluronic acid, a substance that occurs naturally in our connective tissue, to plump—questions the value added with synthetic fillers. If lumps or bumps appear after an injection of hyaluronic acid filler, Brandt says, the body will eventually eradicate them, thanks to hyaluronidase, an enzyme already present in humans. If such complications occur with Radiesse or other synthetic fillers, he contends, they’re more difficult to reverse. Goostree counters that with proper technique, those problems shouldn’t occur in the first place. “And if you have extra swelling or something that feels like a lump,” she says, “you can inject a steroid in it and that usually smooths it out.” Bumps, she adds, can also be massaged away after injection or removed surgically, if necessary.

Either way, Brandt points out, improvements seen with hyaluronic acid fillers might actually last longer than the six months previously thought, especially in patients who use them regularly. A recent University of Michigan study suggested that Restylane not only temporarily fills wrinkles but also induces collagen growth.

ArteFill, Sculptra and Radiesse generally cost more per visit than hyaluronics. One syringe of Restylane starts at about $500, whereas Radiesse starts at $700. But that won’t necessarily up the revenue stream for doctors. Shorter-acting products keep patients coming back to the office, and while they’re there, they just might throw in a microdermabrasion session or some laser hair removal. “I have to develop a relationship with patients,” says New York facial plastic surgeon Richard Westreich. “A single treatment and I never see them again? That’s not so enticing for me.”

Jonah Shacknai, founder and CEO of Medicis Pharmaceutical Corporation, which makes Restylane and Perlane, is steadfast in his commitment to fillers with a more limited life span. While he admits that the company is looking into longer-lasting forms of hyaluronic acid, he’s thinking in terms of adding “months, not years.” Using permanent plumpers in a human face, he says, is “putting a static product in a dynamic place.”

That is indeed a concern of medical professionals who caution that while these fillers stay in place, your face is constantly changing. “The concept of something that goes in permanently and then things age around it is something that none of us knows how we’re going to deal with in the future,” says Vito Quatela, a facial plastic surgeon in Rochester, New York, who is also president of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. “My preference is a filler that lasts somewhere in the one- to two-year range.”

While doctors are just getting acquainted with the new fillers, several other options are already on the horizon. Two implants—VeraFil and Perma—are being presented as alternatives to pout-plumping lip injections. VeraFil, which the FDA recently cleared for use on under-eye hollows and is already being used off-label for lips, is a deflated tube that is inserted via a three-millimeter incision and then filled with saline. “We inflate it all the way up and then we go up and down to find the right volume for the patient,” says James Newman, a facial plastic surgeon in San Mateo, California, who helped develop the implant with Evera Medical. The procedure, done under a local anesthetic, takes 15 to 30 minutes and is reversible only with further surgery. Perma, a soft, solid silicone implant that comes in nine different shapes and sizes, was also greenlighted by the FDA for use in the chin, nose and cheeks, but doctors are experimenting with it in the lips as well.

Both sound promising, but for some, memories of the SoftForm lip implant, which was approved by the FDA in 2000 and then phased out of the market in 2005, are all too recent. Because lips are always moving, the implant had a tendency to migrate, says New York dermatologist David Orentreich, adding that “the ease of using fillers in the lip is hard to beat.”

While there’s plenty of competition on the filler front, up until now, Botox has had a stronghold on the muscle-freezing market. But a brand-new, much longer-lasting procedure is threatening to rival its dominance. GFX, a device that uses radio-frequency energy to target motor nerves (it’s been used for decades by cardiologists), is now being tested on the nerves that control the “elevens,” the vertical lines that can form between the eyebrows. A thin probe is inserted into the face via two to four needle punctures, and the nerves are injured so that “they can’t conduct the signal to the muscle as strongly,” says Newman, who is also involved in GFX’s clinical trials and is an investor in the technology. “We can injure the nerve for a much longer period of time than Botox can,” he says, adding that GFX is not meant to stop muscle activity 100 percent, as Botox initially does. “If patients want to really scowl at somebody, they can still have some activity.”

No matter how enthusiastic doctors are, many of them say that semipermanent options are not for first-time patients. Rather, they’re for an experienced group who have had, well, their fill of fillers and temporary fixes.

But while it’s safe to assume that furrowed brows will never be in style, other trends are less predictable. The full lips that are in vogue today may very well be passé tomorrow. Westreich thinks the more permanent procedures are akin to getting a lifelong hairstyle: “A very small subset of people would want that; they’ve had the same bob since 1978,” he says. “But most people would say, ‘The Jennifer Aniston cut I had 10 years ago—I’m really happy I don’t have it now.’”

Helen McArdle/Getty Images