So the Alt-Right Just Discovered Modern Art

“Seven hundred years after the start of the Renaissance and this is where we’ve arrived?” Paul Joseph Watson, a YouTube personality and InfoWars editor, wrote earlier this week in what at first sounds like a striking and significant realization from an extreme right-winger—one who actually dared to criticize Donald Trump for retweeting Islamophobic videos from a far-right British political party.

Instead of seeing the light about the current state of politics, however, Watson was suddenly simply discovering and coming to terms with the entire past century of art. “We musn’t [sic] feel ashamed to call out abstract modern art for precisely what it is,” he says in a new video for InfoWars that goes on to make the old, tired argument, uttered by tourists at museums, that modern art is “easy”—even though that also would mean pointing out that “modern art” actually refers to art made between the 1860s and 1970s, while the video, titled “Latest Atrocities in Modern Art,” is largely dedicated lambasting art made today.

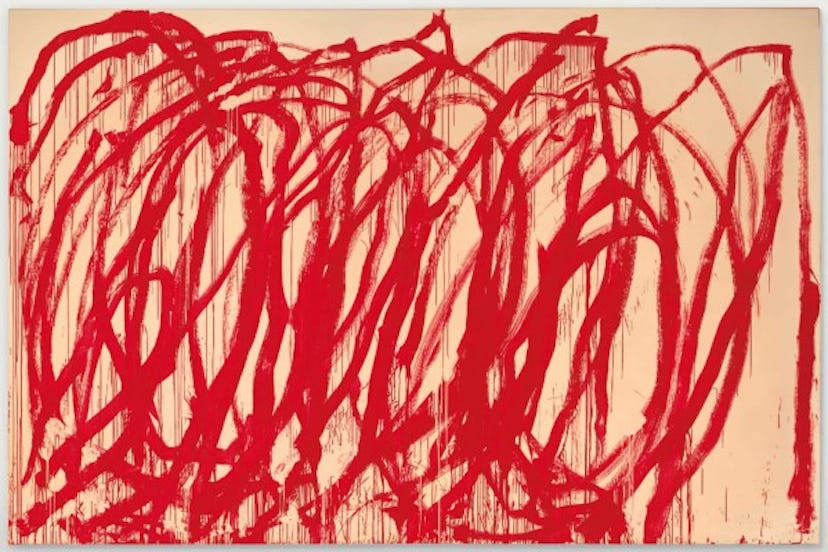

With the persistently controversial $450-million Leonardo da Vinci painting Salvator Mundi as his starting point, Watson kicks off his tirade with another work—or in his words, “monstrosity”—that sold at the same auction: Cy Twombly’s Untitled, the largest painting from the late artist’s famed Bacchus series, which, to Watson’s disbelief, was purchased for $46 million, even though he finds it “resembles what would probably happen if a two-year-old toddler was left on its own with a bottle of ketchup.”

The thing is, Watson is a bit late to the game here in deriding these types of abstract, more conceptual works. The art world—not to mention much of the world at large, like those who keep buying those “Modern Art = I could do that + Yeah, but you didn’t” tea towels and mugs sold in so many museum gift shops—actually got there decades and decades ago. (In his defense, the painting that offended Watson so much was created just over a decade ago, in 2005, though Twombly, now dead, is seen as a fixture of modern art.)

In what’s unintentionally something of a history lesson, given that he got the timeline so off, Watson somehow did the impossible—he tackled the subject of modern art without at some point mentioning Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, who are not only two of the most famous artists to emerge from that time period, but ones who dedicated much of their very practice and spare time to pointing out the art world’s inconsistencies and idiocies that Watson is just discovering. In fact, it’s thanks to the art world’s absurdities that Duchamp is famous in the first place: exactly 100 years ago, he played a practical joke on his fellow exhibition directors by submitting a urinal as a work of art, challenging his colleagues to consider their perception of value—and inventing conceptual art at the same time.

The artists who these days are exhibiting “literally trash,” as Watson says, are following in Duchamp’s footsteps, though Watson seems incapable of accepting that there is a “concept” behind some of their works—especially when they’re made by a “transgender artist” or a “Black Lives Matter-supporting ‘performance artist'” with a “giant fat a–.” Many of the actually present-day works he lashes out at, however, are deeper than they appear on the surface, tackling police brutality against African Americans, or, in the case of the videos of Keith Haring dancing shown at MoMA, which Watson says “remains as cancerous as ever,” serving to document a moment in time.

Lucio Fontana, *Concetto spaziale*, 1960.

“The age of Trump derangement syndrome has only intensified the belief that anything can be considered art, if it serves to amplify some demented far-left political cliché,” Watson argues. Hilariously, though, the works that that get him most worked up while making this point—largely undecorated canvases by established artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Lucio Fontana—actually date back to the early ’60s, long before the Trump administration. Plainly ignoring the fact that he missed the boat for calling them out by more than half a century, Watson continues, “What kind of damage is all this doing to the fabric of Western civilization? If this is what we call high culture—an endless parade of meaningless debris that promises nothing and delivers nothing—what does this say about our society? What does this say about our contribution to the grand tapestry of mankind’s collective achievement?”

Warhol, in fact, had some of the same questions back in the ’60s. Except, he asked them of the types of works that are so dear to Watson—who values “beauty” above all, and particularly the idea of “objective beauty,” which apparently doesn’t include black women with noticeable derrières—and so many of his fellow classics-loving right-wingers. When Warhol, who remains beloved in part precisely because he was so blatant in cheating the system—mimicking pop culture, jacking up the price, and employing a team of assistants to do his work just like everyone from Michelangelo to Jeff Koons has done over the years—heard that the Mona Lisa was on its way to New York in 1963, he simply remarked, “Why don’t they have someone copy it and send the copy, no one would know the difference.”

Andy Warhol, *Campbell’s Soup I*, 1968.

Watson left out Warhol in his scathing history lesson, but he did manage to unearth an artist who breastfed her dog as a performance. This, too, is tired, already-broken news—that some art really is just bad. So too is the news that the art world—just like, for example, the Trump administration—is corrupt.

“The entire industry is a price-fixing scam, where galleries and auction houses, in collaboration with elitist collectors, keep values grossly inflated. Collectors also gift crappy inflated modern art as a ‘charitable donation’ so they can avoid paying taxes. Others buy shitty modern art simply as a way to launder money,” Watson says, explaining a phenomenon that’s been going on for a decade. And in more recent news, this week Donald Trump once again attempted to repeal the Affordable Care Act so that he could cut his own taxes by over a billion dollars.

Related: A Brief History of Donald Trump’s Unrequited Love of Andy Warhol, Who Called Him “Cheap”

See Kendall Jenner, Performance Artist, Channel Icons Like Marina Abramovic and Yoko Ono: