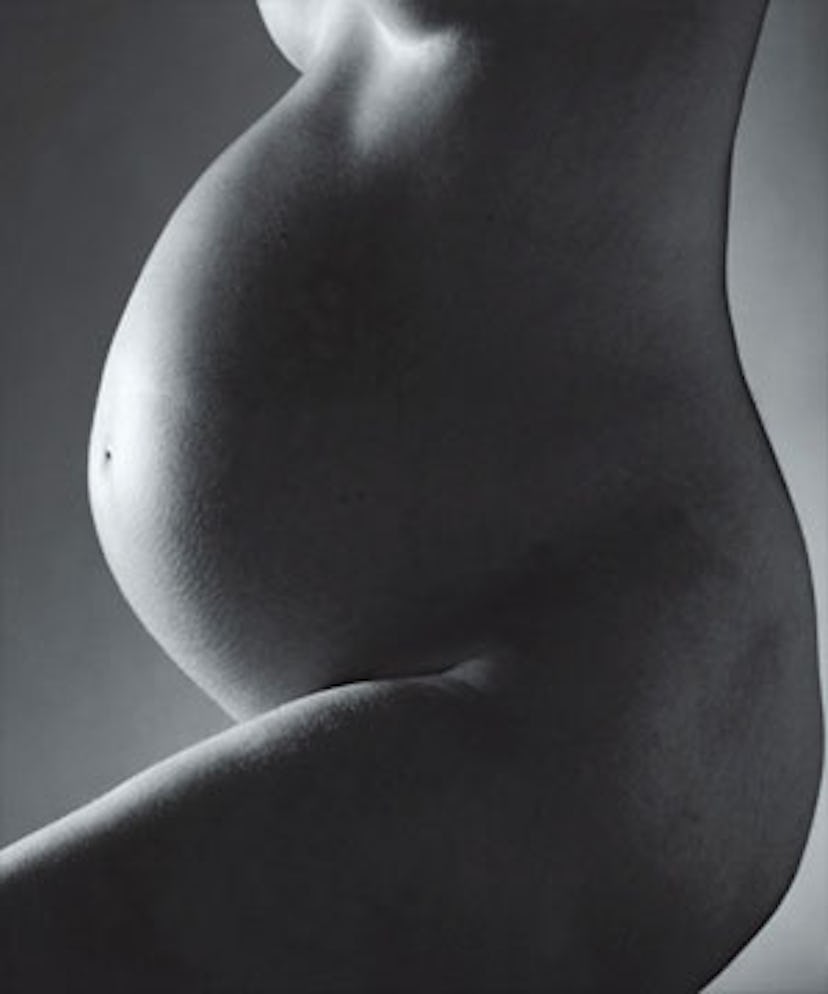

Pregnant Pause

After trying to conceive for nearly two years, Jennifer, a then 36-year-old New York journalist, made an appointment at one of the city’s top fertility clinics. When tests of both her and her husband came back normal, doctors gave them a frustrating diagnosis: unexplained infertility. Loosely defined as an inability to get pregnant after a year of trying when both partners’ reproductive organs seem to be functioning normally, it’s a label that, by some estimates, is applied to as many as 30 percent of fertility patients. Because Jennifer, who asked that her last name not be published, was over 35, her doctor recommended Clomid, a pill that stimulates the ovaries to produce more eggs, and intrauterine inseminations (IUIs). When that course failed, treatments were ratcheted up to include injectable drugs, but they didn’t work either. The next step was in vitro fertilization (IVF), which would have required her to inject higher doses of fertility drugs and have eggs harvested from her ovaries. Embryos, created in the lab, would then have been deposited into her uterus. It was at that point that Jennifer put on the brakes. “I said, ‘Wait a minute. Time out,’” she remembers. “Why do I need all of this if they can’t find anything wrong with my body?”

Now, some fertility experts are beginning to ask the same question. Though much about reproduction remains a medical mystery, many “unexplained” infertility cases, they say, can be explained with deeper sleuthing. These doctors contend that physicians should be working harder to pinpoint the reason for a woman’s inability to conceive before starting her on a program like Jennifer’s, one that can be expensive—at $10,000 to $15,000 per cycle, IVF is not covered by the majority of insurance plans—physically stressful and, of course, emotionally fraught.

Among them is Sami S. David, a Manhattan fertility specialist who, in 1983, was part of the first team of doctors to successfully perform IVF in New York. These days David, an assistant clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, no longer does the procedure, preferring instead to serve as what he calls “a medical detective,” searching out the hidden causes of infertility in his patients. It’s a skill, he believes, that has fallen by the wayside at a time when success rates from assisted reproductive technologies like IVF have been on the rise. “When I was starting out, we were taught the basics: Do an overall medical evaluation, perform tests, make a diagnosis, then treat a patient,” he says. “I believe this is still the right way to treat infertility. You need to make a diagnosis before you treat a problem. That’s a step that’s being skipped. Maybe doctors don’t care about making a diagnosis because the attitude is, ‘We can make you pregnant with fertility drugs, no matter what the problem is.’”

Over the years, David says, he’s helped countless couples with so-called unexplained infertility—some of whom have already failed at IUI or IVF—conceive with low-tech remedies. He favors a holistic approach, often working with acupuncturist Jill Blakeway to help patients deal with stress and talking to both partners in depth about every detail of their lifestyles. In the course of such conversations, he says, he’s come across men who were unknowingly damaging their sperm by taking scalding baths every day or by spending hours with a hot laptop perched on their pelvises. “I’m not against IVF. I’m pro-IVF—for the women who need it,” says David. “What I’m against is the fact that, as physicians, we’re not spending enough time speaking to the patients, studying the tests. Many fertility doctors pretty much know before they walk into the exam room what they’re going to recommend: a couple of Clomid cycles, then inseminations, then in vitro.”

The standard fertility workup at most clinics includes hormone-level tests; a hysterosalpingogram (HSG) test to rule out blockages in the fallopian tubes; and a semen analysis to determine sperm count, shape and motility (or swimming ability). David says he often finds overlooked causes of infertility by performing a simple postcoital exam the morning after intercourse to evaluate the quality of a woman’s cervical mucus and to assess whether sperm are alive and moving normally. If the sperm are dead, David says, the vaginal environment might be too acidic, for which he recommends a baking soda douche before intercourse. If the cervical mucus is too thick to allow sperm to swim, he prescribes an over-the-counter cough medicine like Mucinex. “Many of my colleagues don’t do this test because they have all read the same paper that says some people who have a bad [post]coital exam still get pregnant and some people who have good postcoital exams don’t,” he says. “But my question to them is very basic: Is a woman more likely to get pregnant with live sperm inside of her or with dead?”

David also believes that bacteria can cause infertility, a view that some in his field don’t share. Many doctors do cultures of the cervix to check for chlamydia and gonorrhea, but David contends that other bacteria—such as mycoplasma and ureaplasma—can also interfere with conception, whether present in the woman or the man. “Most doctors do cultures of the cervix, but many of them aren’t looking for these more routine bacteria,” he says. “And very rarely do they do cultures of the semen, which I think is crucial. I’ve seen a number of cases of E. coli and staphylococcus in the sperm. You give them antibiotics, and they get pregnant.”

Harry Fisch, a specialist in male infertility, says he, too, often finds that antibiotics lead to pregnancy. “It’s amazing,” says Fisch, who is the director of the Male Reproductive Center at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia, “but [bacteria] is overlooked all the time.”

Such was the case with Jennifer, the aforementioned journalist. Her failed inseminations eventually led her to David, who promptly diagnosed ureaplasma bacteria in both her and her husband and an acidic vaginal environment. He prescribed antibiotics and a baking soda douche. One month later she was pregnant with her daughter.

It is, of course, possible that Jennifer would have become pregnant without David’s fixes. Richard Paulson, the director of the University of Southern California’s fertility program, points out that “the population of women with unexplained infertility has a pregnancy rate of about 3 percent per month with no treatment. That doesn’t sound like a lot,” he says, “but it adds up to all of these anecdotal cases where a patient says, ‘I took cough medicine’ or ‘I took antibiotics, and I got pregnant.’ The science on these things is just not there.”

Like Paulson, Norbert Gleicher, medical director of the Center for Human Reproduction, a fertility clinic with offices in New York and Chicago, believes that such low-tech fixes are rarely of use. He does, however, agree with David’s basic premise that diagnostics in the fertility field are not what they should be. His 2006 paper, “Unexplained infertility: Does it really exist?,” published in the journal Human Reproduction, kicked off a lively debate on the subject. Gleicher’s answer to that titular question is a resounding no. “How much evaluation is done and how deep that evaluation is varies hugely between practitioners,” he says. “Therefore, you find very different levels of so-called unexplained infertility between various physicians.”

According to Gleicher, many women who are labeled as “unexplained” are actually suffering from fallopian tube disorders. To get a picture of the tubes, most infertility patients undergo an HSG test, in which dye is injected into the uterus and flows through the fallopian tubes. But Gleicher believes that many doctors focus only on whether the tubes are free of blockages—whether the dye can pass through them—and neglect to determine whether the tubes can adequately perform their functions. If a patient has endometriosis, for example, the tubes can become scarred and thus less elastic, which makes it difficult for them to ferry the fertilized egg to the uterus. The elasticity of the tubes can be measured by the pressure needed to force the dye through the tubes. “There’s data in the literature that if the pressure goes above a certain point, you don’t see pregnancies,” says Gleicher. “This is often overlooked.”

But the more frequently missed tubal abnormality, says Gleicher, is a condition in which the delicate, fingerlike folds at the ends of the tubes get glued together, thus preventing the tubes from performing their other important function: grabbing the eggs as they’re released from the ovaries. The HSG dye eventually will pass through anyway, he says, “so the HSG will come back normal when in reality this tube will rarely, if ever, allow the egg to be caught.” If the physician studies the HSG more carefully, he insists, the doctor will notice the tube swelling as pressure builds, forcing the dye through. In such cases, inseminations are of little use, and IVF, which bypasses the tubes, is the patient’s only real hope of conception.

Still, says Gleicher, the number of women with overlooked tubal abnormalities pales in comparison to those with undiagnosed premature ovarian aging. According to Gleicher, who is a visiting professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Yale University and editor in chief of the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, half of women diagnosed with unexplained infertility actually suffer from this condition. Whereas in most women the ability to conceive and carry a child to term begins to fall off sharply at about 37 or 38 and ends altogether at about 45, for approximately 10 percent of women, says Gleicher, those milestones can occur much earlier. One way of determining the quality, or “age,” of a woman’s ovaries is to test the level of follicle-stimulating hormone, or FSH, in her blood. Generally, women with FSH levels lower than 10 are considered normal. The problem, says Gleicher, is that women in their 20s are judged by the same standard as women in their 40s. “If you’re 9.9 at age 45, you have great ovaries,” says Gleicher. “But if you’re 9.9 at age 28, your ovaries are not aging on the standard curve.” Gleicher advocates that doctors abandon the universal cutoff and instead take into account a patient’s age. By his system, for example, a woman younger than 33 should have an FSH of less than seven.

This aggressive approach translates into a quicker path to IVF for more young women. His worry, he says, is that missed diagnoses of premature ovarian aging are leading women to waste precious chunks of their reproductive years “futzing around” with therapies like Clomid and insemination when they should be on a fast track to IVF.

However, Zev Rosenwaks, who is director of the top-ranked Center for Reproductive Medicine and Infertility at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell, cautions against relying too heavily on FSH levels when determining how to treat patients. “FSH is a relative test of the probability of conception, but it is not absolute,” he says. “We’ve had hundreds of exceptions in our program where women have been told that they will never have a baby with their own eggs because of FSH elevation and then they’ve gotten pregnant with their own eggs. There are many, many different parameters that you can look at [such as estrogen level and follicular count] which, together, actually give you a better index of a woman’s probability of achieving a pregnancy. FSH alone doesn’t do it.”

Still, Rosenwaks does agree that “these days many couples are categorized as unexplained not having had a complete workup. Maybe they have not had a laparoscopy [a microsurgical procedure that allows doctors to look into the pelvis in order to check for and sometimes repair damage from conditions like endometriosis] or they have gone into IVF very quickly because their age justifies it.”

In Richard Paulson’s opinion, skipping such tests can be a good thing. He and many other IVF specialists believe that the standard course of IUI with Clomid and, if that fails, IVF, remains the right approach for women over 35 who receive diagnoses of unexplained infertility. While the premise set forth in Gleicher’s paper—that it’s essential to have a specific diagnosis before beginning treatment—might sound logical, Paulson insists that it doesn’t hold up in the real world. In fact, he believes too much testing can be a waste of time and money. “Twenty years ago, we used to subdivide unexplained infertility into at least 10 other subcategories: cervical mucus problems, subtle ovulatory problems and so on,” he says. “But it turned out that none of those subcategories made any difference in terms of the best way to treat the patient. I could spend thousands of dollars doing additional tests to give them a more specific label than unexplained infertility, but in the end we would start them all on the same treatment: IUI with Clomid, which has been repeatedly shown to increase pregnancy rates in the unexplained infertility population from 3 percent a month to 10 percent a month.”

According to Paulson, the low-tech fixes like cough medicine or antibiotics that David and Fisch recommend fritter away months—months that women over 35 shouldn’t be cavalier about wasting. And skipping Clomid and inseminations, as Gleicher recommends in many cases, deprives couples of a lower-cost treatment (about $500 per month for IUI versus about $10,000 for IVF, in Paulson’s estimates) that has been shown to significantly improve pregnancy rates.

What’s important to keep in mind, says Rosenwaks, is that every case is different. “In medicine, generalization holds only so much, so I don’t think you ought to exclude anything necessarily,” he says. “A patient’s history should dictate how much and what kind of testing should be done.” In the end, as anyone who has struggled to conceive knows, there are many paths to parenthood.

Michael Salas/Getty Images