Intimate Companions

For decades, the “extra man” was a fashionable woman’s ultimate accessory. But Rob Haskell wonders, are walkers a thing of the past?

In April, an Upper East side mother of four entered the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the Society of Memorial Sloan-Kettering spring ball with a younger man as wholesomely handsome as he was unsettlingly familiar. Tall, scrubbed, smiling brilliantly, with his well-cut dinner jacket making an elegant amuse-bouche out of the underlying musculature, this ephebus might have caused the female brows to collectively furrow if it weren’t for all the botulinum toxin contained therein.

But then he said hello. Of course! It was Nick—an extremely popular and (phew) openly gay spinning instructor at the East 83rd Street SoulCycle who’d recently moved to New York from West Hollywood. Nick’s clients were more accustomed to seeing him in his signature workout garb: sporty shorts and a T-shirt with deep cutout armholes stretching to his waist that he often removes mid-class to the screeching approbation of a roomful of rail-thin sweat-soaked spinners. Lately Nick has squired this highly aerobicized mom to a number of charity parties around town—her husband prefers to keep out of the circuit, though he’s happy to write the checks—and is a frequent guest at her homes on weekends.

To all appearances “the walker”—a term W’s founder, John B. Fairchild, first used in the pages of Women’s Wear Daily in the seventies to describe those spiffy, quick-witted, usually gay men ever ready to accompany a socialite on her daily rounds—is alive and well.

Or is he? Just as paleontologists believe that a sudden change in the earth’s climate altered the dinosaurs’ food supply and pushed them to extinction, some social observers wonder whether cultural shifts in the decades since Truman Capote walked Babe Paley have eaten into the walker’s steady diet of rich women needy for nonsexual male attention. Indeed, there are those who believe that the mauve damask curtain fell on the age of walking 10 years ago, when Johnny Galliher died in his sleep in a two-bedroom apartment on Manhattan’s East 63rd Street.

Galliher, whom Count Lanfranco Rasponi, in his 1966 book The International Nomads, called “a favorite extra man…whose Irish dimples some hostesses find irresistible,” was born in Washington, D.C., in 1914. Little is known about his background; he had the walker’s talent for self-invention and often claimed to be descended from Pocahontas. As a teenager, Galliher was taken under the plush wing of Washington, D.C., heiress and socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean, the last private owner of the Hope Diamond. (Galliher was often tasked with holding it in the pocket of his suit jacket when McLean lent the stone to her daughter, his frequent date, who never cared to wear it in public.) With his etched features, dark hair, impeccable manners, and easy social style modeled on that of Noël Coward and Cole Porter, both friends and mentors of his, Galliher managed to magnetize the world’s most glamorous folk, from Elsie de Wolfe to Mica Ertegun, Mona Bismarck to Pat Buckley. Apart from his winnings from a regular game of gin rummy, he had no clear source of income—but he wasn’t a mooch. His aim, say those who knew him, was quite simply to have a nice time. Like all walkers of the old school, Galliher pursued his romantic interests outside society. His ladies knew that he dated men, but they never asked questions.

“Back when sexuality wasn’t discussed,” says David Patrick Columbia, a social historian and a cofounder of the website Newyorksocialdiary.com, “women only knew that there was a type of man who paid attention to them instead of to their horses or yachts or guns or gambling.” This was the courtliness of the closet: a covering-over of desires with manners—which could be willingly offered to and gratefully received by women.

By wearing the badge of confirmed bachelorhood so jauntily, Galliher, in fact, represented a second wave of walkers—men who were never direct, exactly, but never deceitful either. When elegant women first ventured out in public a century ago, of course, the walker’s ultimate goal could only be marriage—an ambition realized in spectacular fashion in 1901 at the Philadelphia Episcopal Cathedral, when Elizabeth Drexel, the immensely rich and newly widowed heiress to a banking fortune, wed Harry Symes Lehr.

Lehr may be the original walker, and if the term is today considered by some to be a slur, then credit goes to him. Born into a respectable Baltimore family, he moved to New York and became the Gilded Age heiresses’ favorite young man. He is said to have first captivated Caroline Astor when, seeing her dressed all in white at a party, he cried, “You’ve too much white on! You look like a ghost! Here—” before handing her a red rose from a vase on a nearby table. Lehr’s coterie quickly included every one of the so-called Big Four—Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs, Mrs. Oliver H. P. Belmont, Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish, and Mrs. Astor herself—and he parlayed these connections into all manner of perks: free clothing and baubles from the era’s leading purveyors, such as Wetzel, Kaskel & Kaskel and Black, Starr & Frost, so long as he whispered the names of those houses into his duchesses’ ears; free first-class rail travel (Mrs. Fish’s husband was head of the Illinois Central Railroad); a suite of rooms rent-free in his friend Tom Wanamaker’s large Fifth Avenue apartment; and, naturally, lunch at Sherry’s, turn–of–the–century New York’s most stylish restaurant. (Lehr more than earned his keep there, successfully enticing Mrs. Astor to Sherry’s on her first ever visit to a public restaurant.)

A century later, Lehr might have been New York’s most powerful publicist. Back then, he was simply waiting for a rich woman to rescue him from his hawker’s purgatory, and he found her one evening at a Metropolitan Opera production of Lohengrin. Elizabeth Drexel admired his powerful build, blond locks, and, she wrote years later, that “pleasant, lazy voice, curiously high-pitched,” which seemed to ignite brilliant conversation all around him. Soon they were engaged, and on their wedding night, Mrs. Lehr ordered up the usual luxuries of the day—quail in aspic, a cabinet of cigars—but was soon informed that her new husband had no intention of ever visiting her bedroom. “Have you so much to complain of?” he asked. “At least I am being honest with you. How many men in New York, how many among our own friends, if it comes to that, have entered their wives’ rooms on their wedding night with exactly my state of mind?”

According to her diaries, Elizabeth Drexel accepted this mariage blanc. After all, King Lehr, as he was called by friends, elevated her social position and got her invited to the best parties in Newport and Paris. In return, she set him up with an annual allowance of $25,000 (the equivalent of $750,000 today).

With the flowering of café society in the thirties, journalists who chronicled the goings-on of fashionable folk at venues such as El Morocco, the Stork Club, and 21 became the era’s preeminent walkers. There was Jerome Zerbe, New York’s first society photographer; and Maury Paul, the social chronicler who invented the term “old guard” for the set he favored and who claimed a collection of more than 50 fur coats. But Lucius Beebe, who regularly wrote about café society in his Herald Tribune column in the thirties, was the period’s best-loved extra man. Known for the “outrageous majesty of his appearance,” as one contemporary journalist called it, Beebe favored John Lobb boots, Charvet ties, and Savile Row suits. The radio personality Walter Winchell dubbed him Luscious Lucius—probably a none-too-veiled jab at his sexual proclivities—and Beebe had one of the era’s few openly gay relationships: He met his lifelong partner, Charles Clegg, at the walker hatchery otherwise known as Evalyn Walsh McLean’s house. And although Beebe went on to become the nation’s foremost railroad historian, he described his social position thus: “I consider my function,” he wrote, “that of a connoisseur of the preposterous.”

At 82, Luis Estevez is the last surviving member of the golden age of walking that revolved around midcentury swans Babe Paley, Gloria Guinness, C.Z. Guest, Slim Keith, and the Duchess of Windsor. “I must sound like such a name-dropper,” he says, using the words “best friend” to describe Guinness, Cole Porter, Merle Oberon, Elsie Woodward, Liliane de Rothschild, Betsy Bloomingdale, and Marella Agnelli all in the course of a single conversation. A New York fashion-design star in the fifties known for curvy gowns with fanciful necklines, Estévez could never be an extra man quite in the manner of his good friends Bill Blass and Billy Baldwin—after all, in 1953 he had married the well-born model Betty Dew (Hubert de Givenchy served as his best man) to appease his old-school Cuban parents. “The real walkers didn’t have wives—otherwise the numbers would be off,” he chuckles. “Betty and I had a straight social life, because social life was straight—or it was supposed to look that way. But I did lots of gay things, and so did she.”

The walker’s sexuality, Estévez says, was never challenged—even by the red-blooded likes of William S. Paley. Of course, there were rare exceptions: Slim Keith, the California model–turned–British noble, spent so many nights out with Bill Blass that she determined it would be more convenient to have him as a lover. One summer weekend she invited him to Nantucket, and on his first night on the island, Blass changed for dinner and was surprised to find a candlelit table set for two. Immediately understanding Keith’s purposes, Blass dined politely, packed his bags, and never spoke to her again.

Estévez, who now lives in Montecito, California, regards today’s social stars as “tarty” and suggests that the walker became unnecessary once the Pierre’s ballroom opened up to pop stars and reality-TV icons. “In the fifties and sixties, women of style required men of style. So the walkers and the wives depended on each other,” he says. “Like Jerry Zipkin: He was a total shit, but he knew how to make a woman feel noticed, important.”

Zipkin, the heir to a real estate fortune, is the standard by which all other walkers are measured. The secret to his success? “I believe a woman can have a best man-friend, and a man can have a best man-friend,” he said in a 1981 interview. “But a woman cannot have a best woman-friend. A best woman-friend will do her in.”

Woman’s best man-friend—this was Zipkin, razor-tongued and limo-ready, possessed of a collection of jeweled cuff links to rival Imelda Marcos’s shoes. His walking spanned two eras: There were C.Z. Guest and the Duchess of Windsor and, later, the Le Cirque set, including Louise Grunwald, Chessy Rayner, Pat Buckley, and his favorite bony elbow, Nancy Reagan. Famously frank, his dish-and-take style occasionally landed him in trouble. (Zipkin once approached Anne Slater at a party and told her, “I don’t like the color of that lipstick.” “Well, Jerry,” she replied, “you shouldn’t wear it then.”) Zipkin wasn’t above feuding with the women in his life. He fell out with Buckley one year at the Met Costume Institute Gala when she seated his walkee that night, the Duchess of Cadaval, next to her husband and placed Zipkin somewhere out in the tundra.

“Jerry was surrounded by smart, witty women,” says Cornelia Guest, who herself was chaperoned—the word she prefers—by Halston as a teenager, and whose famous mother, C.Z., often enlisted the services of a walker. “Nowadays guys have to listen to some movie star gab all night. And the guys have so much social ambition themselves that sometimes it looks like the women are walking them.”

Indeed, current society is so diffuse, so full of outcroppings, that it would be difficult to name an heir to the Zipkin estate. In Los Angeles, Alex Hitz is still mentioned as escort to the old guard, but that city’s agents and publicists—the Huvanes, Bryan Lourd—do Hollywood’s most conspicuous walking. In New York, Dimitri of Yugoslavia is a modern-day double threat in the mold of Coco Chanel’s jeweler, the Sicilian duke Fulco di Verdura: He has a title, and he makes expensive baubles. Young fashion designers walk their favorite clients: Prabal Gurung walks Elettra Wiedemann, Jason Wu walks Olivia Chantecaille, and the Proenza Schouler boys walk the Traina girls. In London, the billionairess Lily Safra can now count on Elton John, once Princess Diana’s walker, to ferry her to fetes around town. Kate Middleton, with her still-game husband usually in tow, has yet to anoint a walker. But she will.

Bunky Cushing is a bald and bow-tied Michigan native, a distant and, he says, poor relation of Babe Paley’s who spends his days working as a sales associate for a luxury retailer and his nights presiding over the frozen-haired, diamond-trimmed Chicago set known as Bunky’s Bunch. Cushing embodies the best attributes of the old-school walkers—good humor, great pocket squares—and to them adds a large social conscience. Though he says he knew one person when he arrived in Chicago in 1990, he now rules the social roost, hosting two of the city’s most sought after yearly parties: an author breakfast in June for 85 women to benefit the Jane Addams Senior Caucus and an October luncheon for 200 to benefit the Howard Brown Health Center.

“I’ve done my years as a walker,” Cushing says. “And you can only sit so long listening to how someone’s facelift made her look like Quasimodo.” His fancy friends’ husbands tend to bring to his mind the old image of Ricky Ricardo chuckling at Lucy’s Wednesday Afternoon Fine Arts League meetings. “These husbands are relieved to have some guy take over an aspect of their wives’ lives that they have no interest in,” he says. “They’ll come into the store and say, ‘My wife thinks the world of you, so I just had to come in, meet you, and say thanks.’ That means the world to me.”

Years ago, Buckley told a reporter that she detested the word “walker” because “it connotes something it shouldn’t”—by which she likely meant some amalgam of greed, frivolity, and homosexuality. Good or evil, serious or silly, the original walkers needed two things: a pressed dinner jacket and an agreeable manner. Now that women venture out in groups, or alone, and hostesses worry less about balancing the numbers at their tables, new walkers may bloom for a night or two—Nick, the spinning instructor, for example—but they hardly need to make a career out of collecting cuff links. Fortunately, there are better things for a confirmed bachelor to do nowadays—like marrying another confirmed bachelor.

Still, the women must be entertained. “I will always want a walker,” says Jill Kargman, a gala regular and the author of several social satires. “And I hope other women will, too—I don’t want to sit next to their boring husbands.”

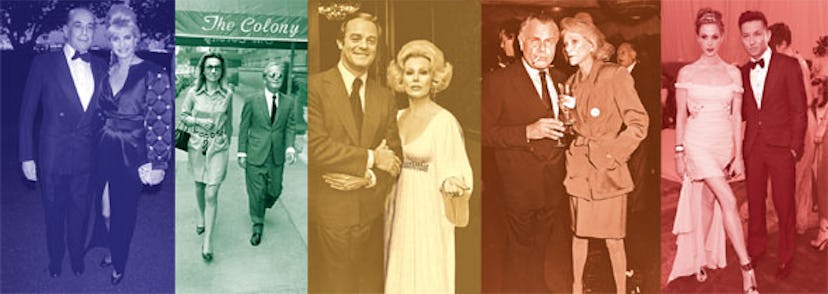

Photos: Lane, Estevez, Blass: Getty Images; Capote: Condé Nast Archive; Gurung: Corbis