Giorgio Armani’s Soft, Easy Suiting Finds a New Audience

As Armani evolves his position on tailoring, a new generation of designers (and fashion enthusiasts) look to his pioneering silhouettes from the 1980s and ’90s.

The first time I fell under the spell of Giorgio Armani, I didn’t even realize it was happening. I was 16 years old, rummaging through the racks of a consignment store in London, when I found a caramel-colored cashmere herringbone blazer with no lining, no buttons, and the light, fluid feel of a really expensive T-shirt. I had never owned anything resembling a suit jacket, but this was different: It fell straight down from my shoulders rather than nipping in at the waist, and the fabric was so thin that I could easily roll up the sleeves. I thought it made me look grown-up, but in a cool, romantic way.

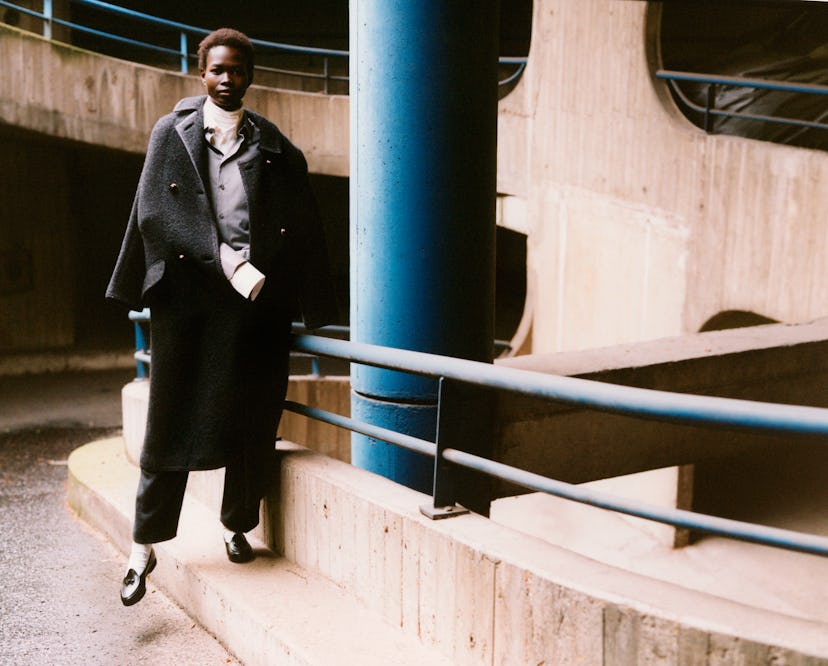

Photographed by Maciek Pożoga in March 2020 in Paris. Giorgio Armani clothing and accessories.

It’s still in my closet, but I hadn’t really thought about it until I was flipping through the huge tome that Armani produced in 2015 with Rizzoli, in which essays by the designer are sandwiched between thick slabs of archival photos. One line in particular struck me, from a section titled “Imagining the Body,” a manifesto of sorts on his approach to the human form. “The body was to be exalted in the name of an energetic naturalness, a vigorous sex appeal, a kind of pride that meant self-awareness, not exhibition,” he wrote. “That was when I conceived the most traditional piece of clothing—a jacket—with a different formula. I removed the stiffness that was inside to give it the suppleness of a cardigan and the lightness of a shirt.”

Photographed by Maciek Pożoga in March 2020 in Paris. Giorgio Armani clothing and accessories.

Although Armani has always held fast to those central tenets, he made a few amendments in his pre-fall 2020 collection. On the runway, cropped, boxy jackets were trimmed with twist braids or fastened with one high-up button, allowing a small triangle of skin to peek out from above the waistband. There were slouchy velvet lounge suits and décolletage-baring blazers with strong shoulders and rounded seams in a color palette of ruby red and deep, shimmering black. It was a playful, modern interpretation of his signature early look. “I wanted to bring it all to a softer level. Even working women feel like expressing their femininity in a more open way today,” he told me a few weeks after the show.

Photographed by Maciek Pożoga in March 2020 in Paris. Giorgio Armani clothing and accessories.

At a time when a new generation of designers and customers—many of whom came of age after Armani’s designs first landed in the U.S.—is knowingly or unknowingly revisiting Armani’s early work, it’s worth remembering just how radical his approach was. As the semiotician Marshall Blonsky wrote in the catalog that accompanied the Guggenheim Museum’s 2000 exhibition on Armani’s work, “He was in the avant-garde of the attack on gender rigidity.”

Photographed by Maciek Pożoga in March 2020 in Paris. Giorgio Armani clothing and accessories.

Inspired by Yves Saint Laurent’s androgynous silhouettes and the contrast of Coco Chanel’s tiny jackets and mannish pants, Armani consciously evolved suiting in a more ambiguous direction. His soft, flowing tailoring changed the way people thought about sensuality: everything unadorned, in neutral fabrics that pooled around the body. In old campaign photographs by Aldo Fallai and Peter Lindbergh, Armani’s suits made women look defiant, like they were making fun of male bravado while simultaneously claiming some of it for themselves. It wasn’t minimalism, with its sexless straight lines, but rather a simplicity that honored the human form.

In the 1990s, a few years after the designer Alber Elbaz first moved to New York City, it seemed like every woman around him was wearing Armani. Their sense of ease and casual elegance were enough to inspire envy. “I said to myself, I wish I was a woman, to have such a suit that feels almost like a pajama and still you look sharp and edgy and smart,” he recalled, speaking on the phone from Paris. “I was trained by Geoffrey Beene and Yves Saint Laurent—really big masters. So I’m lucky in that way, but I’m sorry I was not also trained by Armani.” He added, laughing, “It’s maybe too late for me.”

In campaigns shot by Peter Lindbergh and Aldo Fallai in the 1980s and early ’90s, women pose with an androgynous bravado,

Ever since Armani’s first women’s wear show, in 1975 (top left, comfortable suits that empower the wearer have been central to his work. This year, three-piece suits reminiscent of the one worn by Amber Valletta in 1993 (right) appeared on the runways of labels like the Row, Celine, and Etro—proof that Armani’s influence still reverberates throughout the fashion world.

Formal apprenticeships aside, today’s runways, sidewalks, and screens are the equivalent of Armani 101. Kaia Gerber has stepped out many times in men’s wear–inspired jackets thrown over jeans. The half-Italian designer Marina Moscone, who founded her namesake line in 2016, remembers visiting the Armani boutique on Rome’s Via dei Condotti with her father when she was a child. “Mr. Armani’s tailoring has been the heart of my brand and my collection from the very beginning,” Moscone said. Her core pieces include soft basque blazers, roomy straight-leg pants, and easy slip dresses. For spring ’20, Celine and Etro sent three-piece suits in fluid fabrics down the runway, and the Row’s fall ’20 collection featured several with pleated trousers and high-cut waistcoats—reminiscent of 1990s Armani right down to the charcoal, navy, and cream color scheme. A few days after the show, the writer Rachel Tashjian posted a screenshot from the runway alongside an Armani campaign photo shot by Lindbergh in 1993, of the model Amber Valletta, in a similar style.

I reached out to Tashjian and we sat down to chat, trying to determine why all of this feels so appealing right now. “I think that we were in this period for a long time where it wasn’t really about making clothes, it was about clothing that looked interesting in a photograph,” Tashjian said. “Designers are starting to get really sick of that, and they’re trying to give people clothing that actually functions in life.”

On Armani’s runways in the ’80s and ’90s, suits took on a soft, sexy attitude

We pored over runway images from the past 30 years, scrutinizing models with undone hair wearing tiny sunglasses and big clothes. “It looks really relaxed. It looks so confident. And maybe a teeny bit arrogant, in an appealing way. Arrogant in a different way than we’re used to thinking of fashion and arrogance, because it’s not sloppy,” she said. She paused for a moment. “It’s not Zuckerberg arrogant, where it’s like, I’m going to wear this gray T-shirt because I’m Mark Zuckerberg. It’s arrogant like, Yeah, I know I look great.”