George Condo Recalls His First (and Last) Real Job

In a new group exhibition at Luxembourg and Dayan gallery, famed artists and their assistants who became stars in their own right get reacquainted again. Here, the painter and former Kanye West collaborator George Condo remembers his time working for Andy Warhol.

The only artist I ever worked for was Andy Warhol. I was 23 years old in 1980, and it was my dream job. I was from a small town in Massachusetts and studied Renaissance and Baroque painting in college, so I always read about young artists apprenticing for old masters. After I graduated, I got in touch with an employment agency. They sent me to a gallery where Andy’s master printer Rupert Smith had convinced Andy to do a show. The gallerist needed someone to write the press release for the show and asked me to do it. When they sent it to Andy for approval, he called the gallery back and said, “I want whoever wrote this to come and work as a typist to record what goes on every day at the Factory.” Of course I took it.

Four days after I got there, I started wondering, “What exactly am I supposed to write down?” How a studio assistant ordered steak tartare? How Rupert always yelled at everyone? Then one day, in came a portrait of Diana Ross, and there was a white spot in the middle of the black of her hair. They needed it restored and asked me if I could paint. They gave me a bottle cap, a dab of black paint, and a brush. They put the painting on the floor, and they all stood around me. I put down a tiny dot of black to cover the white, and they were all like, “Wow, that’s amazing.”

I worked at Warhol’s Factory for nine months and it was incredibly intense. They asked me if I wanted to be on the assembly line; I ended up doing all the diamond dusting. I would go in at 10 AM and finish at midnight — it was slave labor. We had to get things done under extreme pressure and execute it perfectly. On top of that, Andy was never at the Factory. He was in his office on 18th Street, and we were printing on Duane Street in TriBeCa. There was a telephone that sat next to the silkscreen machine and when it would ring, Rupert would pick up, listen, and say something like, “Andy’s on the phone. He wants to change the color from purple to black.” So then we would have to rush to change the entire print and make a whole new group of 300 pieces. And there were only about six or seven studio assistants. We made probably 5,000 prints over the course of the nine months I was there.

But working there made me feel like I was in touch with the art gods somehow, to be in contact with that kind of a thinker. So I knew I would have to come up with something as good that was totally different, but equally radical. I thought it might be good to step out so I could think about what that would be. My girlfriend at the time was an actress and she landed this big TV show in Los Angeles. She suggested I move out there with her. I heard that Jean Michel [Basquiat] was heading out there, and Larry Gagosian was giving him a place to live. I figured, if Jean Michel is going to L.A., I’ll get out of here too. And I had had enough. The Factory was too intense. It was the last job I ever had, thank god.

It’s surreal seeing my work exhibited next to Andy’s almost 40 years later. I printed this work of Andy’s myself when I worked at the Factory, and for some reason that image haunted me after I left. I had to get it out of my system by creating my own version of this character. I wanted to make it as freaky as I possibly could. It was lodged somehow in my subconscious, and I didn’t let it out until I finally painted it in 1998. I remembered the days at Andy’s and realized I could silkscreen in a painterly way. So in the late ’90s I decided I wanted to get back into silkscreens. I felt it was a medium that hadn’t really been explored outside of Warhol.

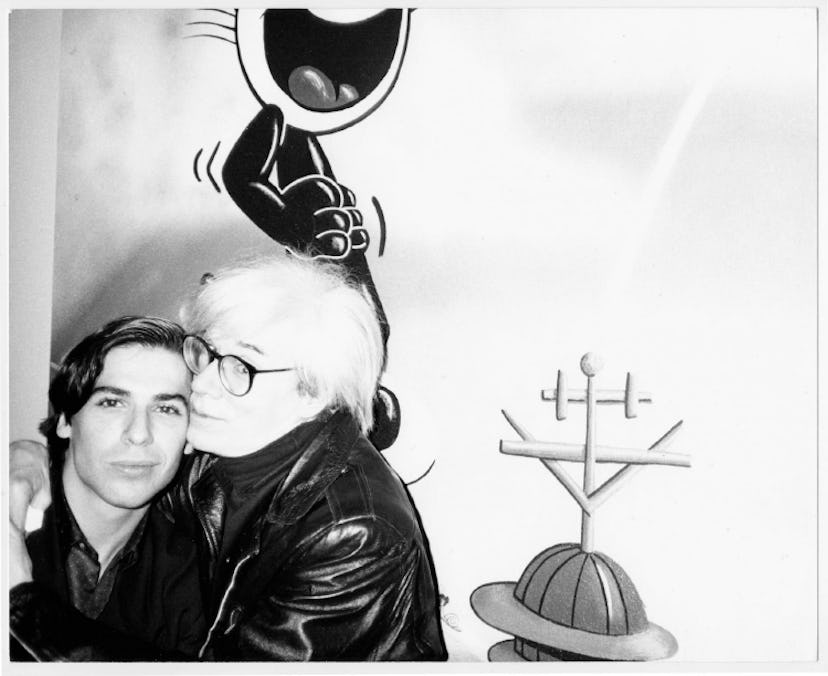

Warhol on the left, Condo on the right.

I met Andy twice while I worked for him. The first time was when I brought him some prints; the other time I was too shy to even say anything. Not to mention that Rupert told the assistants that when we saw him, we weren’t allowed to say anything. I formally met Andy when he and Keith Haring bought one of my paintings in an exhibition in the East Village years later. I remember the art dealer saying, “Andy is here and he wants to meet you.” I was petrified that he was going to recognize me and realize I’d worked for him. Looking back, I wish I had the nerve to tell him that I worked for him when I was 23, but I never did. Then I met him again at Keith Haring’s studio in 1985; I was living in Paris and needed a space to work in New York, so I worked at Keith’s a lot. I remember Andy came down and said, “I really love your paintings.”

He was very talkative. By the time I actually met him, he and I were the only two people living uptown — all the artists were living in the Village, so we would share cabs uptown together and talk. I know one of his famous quotes is: “I am deeply superficial” — but it wasn’t true. He loved to talk about art. We would talk about Old Masters paintings, what was happening in Rome, Venice. He was a super intelligent guy. Gore Vidal once said Warhol was the only genius he met with an IQ of 40, but that wasn’t true. And he was the furthest thing from superficial. He was an amazing person.

As told to Gillian Sagansky.