The Astonishing Art Collection of Farah Pahlavi, Former Empress of Iran, Finally Comes to Light

Farah Pahlavi, née Diba, the exiled empress of Iran, has many a tale to tell. For now, she is sharing with the world the remarkable art collection she once amassed.

Farah Diba met Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in the spring of 1959, when she was a vivacious 20-year-old, at an embassy reception in Paris. Her widowed mother had sent her to France to study architecture, which was an unusual field for an upper-class Iranian girl. “In those days, everybody wanted their children to become doctors or something in government,” she recalls now. “But I thought, I didn’t want to be just in a room—I wanted to be outside, in nature.”

He, of course, was the Shah of Iran, 20 years older than she, and what she wanted to do in life did not particularly preoccupy him. He was shopping for a new queen—his third—who could give him an heir. They married a few months later, and in 1967 she became Shahbanu Farah Diba Pahlavi, the Lady Shah, Empress of Iran.

Andy Warhol’s Farah Diba Pahlavi, Empress of Iran, 1976; Warhol’s Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran, 1978.

They shared 20 years in power together before the Islamic Revolution swept them both from the Peacock Throne—the symbol of the Iranian monarchy—and out of the country forever, in 1979. He died of cancer a year and a half later, after shuffling from country to inhospitable country. She now lives between Paris and the Washington, D.C., area, but she can mostly be found in Paris.

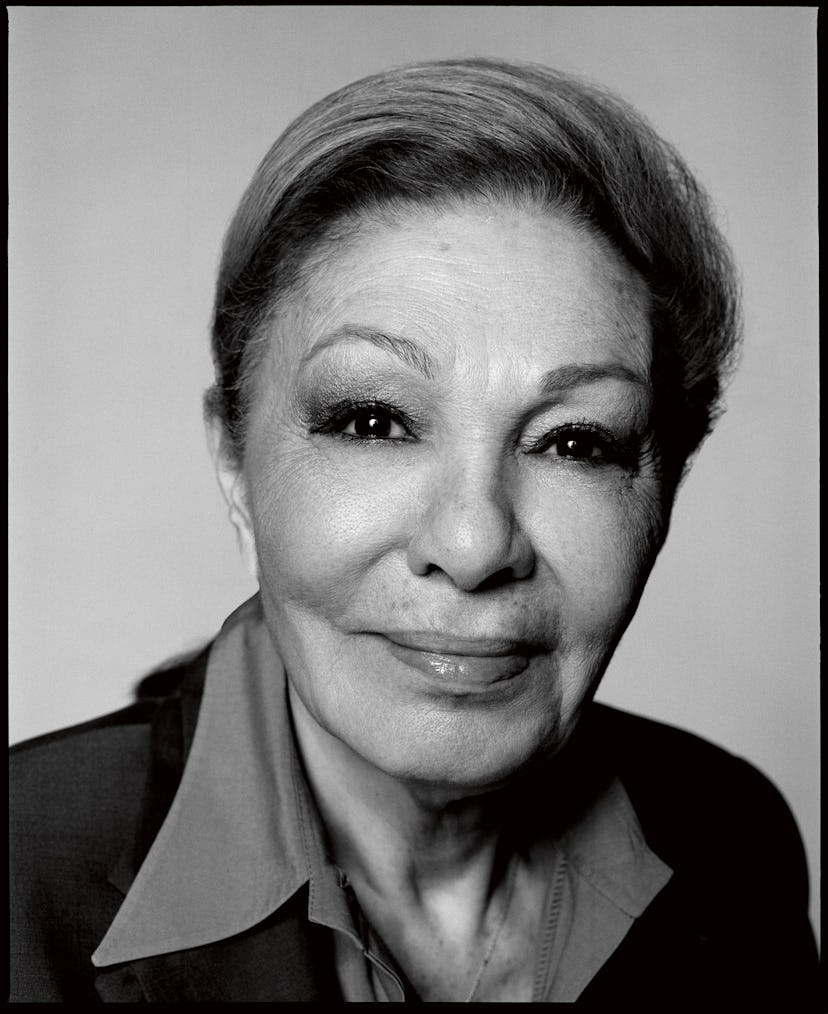

I recently met Her Imperial Majesty, as I was instructed to call her, in the Paris offices of Christie’s auction house. An impressive new book devoted to the art she collected as empress had just been published, and there was to be a big party that evening. This was my first brush with royalty of any kind, but calling her Your Imperial Majesty didn’t feel like a stretch. At 80, she is poised and beautiful, not haughty but with a float-serenely-above-everything quality that must come with the job.

The shahbanu has now spent more of her life outside of Iran than inside. She misses it “every day,” she says with quiet melancholy, but without sentimentality. “There is a lot of sadness,” she says. “There have been times in the past, during exile, when I was really living hour by hour, day by day. You have to keep up your spirit and your strength. I use all the means that there are to feel better—yoga, meditation, which I should do more now.”

Alexander Calder’s tapestry Disque et Gramophone, circa 1970, hanging at Kykuit, the Rockefeller Estate, in New York, during the Shah of Iran and the empress’s visit, in 1975.

Neither Iran nor history has treated the shah very well. He is remembered—fairly and unfairly—for spending Iran’s oil wealth on American warplanes and self- glorifying pageants. Even the modernizing intentions of his White Revolution have been judged as tone-deaf and clueless. He will never be considered one of history’s heavyweights. She, however, is another story. When she reigned, her stylishness was seen by many of her countrymen as a blasphemous sellout to the decadent West. Today her designer outfits look more like the flags of a freedom that has been denied to Iranian women for too long. If the shah is still regarded as a misguided militarist, the shahbanu—whether she intended it or not—is seen by some as an unlikely feminist.

But Pahlavi’s most important legacy—it might just be the longest-lasting of the whole Pahlavi dynasty—is the artwork she championed, bought, and displayed in the museums she founded all over Iran. Many of these institutions have celebrated native Persian treasures over the years: carpets, paintings from the Qajar period, ceramics, and bronzes. Her most noteworthy acquisitions, however, at least to those outside Iran, are more than 200 masterpieces of Impressionist and modern painting and sculpture. That collection, said to be worth several billion dollars, has for the most part been hidden away by the Islamic republic, which remains half-ashamed of it.

Pahlavi and Salvador Dalí, in Paris, 1969.

But those works are finally awakening from their long sleep in a Tehran museum vault and venturing out into the daylight—or at least a few of them are, sometimes. A February exhibition at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art features works by Mark Rothko, Andy Warhol, and Marcel Duchamp. (Not surprisingly, nudes by Auguste Renoir and Francis Bacon will not be included.) Still, given the way things are, it’s unlikely that many of us will get a chance to see any of those paintings—nudes or not—anytime soon. The next best thing is the book that Pahlavi was fêting at Christie’s, Iran Modern: The Empress of Art, published by Assouline. More than a doorstop, it’s like an actual door: 20 pounds, three inches thick, and selling for $895. Staring out from the cover is Pahlavi at her most glamorous, in the silk screen she commissioned Warhol to make of her in 1976—not for nothing was she known as the Jackie Kennedy of the Middle East. The original painting was ripped to shreds by an angry crowd in the early days of the revolution—luckily, one of the only works in the collection to be maimed. “Many years ago, I saw a film on French television that showed the artwork in the basement of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art,” Pahlavi recalls. “I saw that my portrait by Andy Warhol was cut up. When I saw it, frankly, I said, ‘That was stupid. Instead of cutting it up, they should have sold it.’ ” A chronological name check does scant justice to the riches cataloged in Iran Modern. Renoir and Paul Gauguin give way to Fernand Léger and Pablo Picasso, up through Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Jasper Johns. And that’s just the paintings. The sculptures include important works by Alberto Giacometti, and Alexander Calder.

The empress, at the time of her coronation, on the cover of Paris Match, 1967.

Pahlavi began collecting in the early 1970s, when Iran was enjoying a huge financial windfall. “We had the means with the rising price of oil, although our problems also started from there. I thought we should have a museum where young Iranian artists could exhibit, but then I thought, Why not also have foreign art and not just Iranian art? The whole world has our art. We cannot afford to have their ancient art, but we could afford their modern art.” The budget came primarily from the National Iranian Oil Company. For advice on what to buy, the empress relied heavily on Donna Stein, a former curator of drawings and prints at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York. Just as important was input from Kamran Diba, an architect and a cousin of the empress, who also drew the plans for the museum itself. The building of concrete and stone plays quarter-circle shapes against one another in a way that looks both modern and ancient. I saw it up close several years ago, and it is wonderful. The architect took his inspiration from Persia’s ancient wind towers—remarkable brick structures that funnel hot wind over a pool of cool water as a kind of primitive air conditioning. Pahlavi was pleased, too. “The wind towers are so beautiful.”

Visitors view Roy Lichtenstein’s The Melody Haunts My Reverie, 1965, on display at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in 1999.

Those were the years when Pahlavi was making studio visits and meeting the greatest artists of the time. Once, when with Moore, the artist “showed me a little painting and asked everybody who had done it. By chance I said Miró, and I was right! I was very, very proud.” She could easily have squirreled away a Rothko or two on her way out of Iran, but she pointedly did not; she had said she had acquired the collection for the Iranian people. “In 2005, the director of the museum at the time did put on an exhibition of the paintings—not all of them, of course. I am happy that the people saw what they have. I will never forget an Iranian painter lady who told me that when she found herself in front of a Rothko, she had tears in her eyes. That was important to me. Everything is still there.”

The couple with President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, in Washington, D.C., 1962.

Well, almost everything. In 1994, the Islamic republic traded de Kooning’s Woman III, 1953, for exquisitely illustrated manuscript pages of the Shahnameh—the national epic by the poet Firdausi—then owned by the heirs of an American collector. The exchange took place in the Vienna airport, and the de Kooning ended up in the hands of David Geffen, who later sold it to the hedge-fund billionaire Steven Cohen for $137.5 million.

Comfortable as her life in exile has been, Pahlavi feels the displacement keenly. She often quotes a line by an Iranian poet: “The house is beautiful, but it is not my house.” She has also experienced untold pain and misfortune. She and the shah had two sons and two daughters. In 2001, the younger daughter, Leila, overdosed on pills in London. In 2011, the younger son, Ali-Reza, shot himself in Boston. After her daughter’s death, Pahlavi bought a small home outside Washington, D.C., to be near her elder son, Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, and his three daughters. “It’s terrible, and I think about it every day. I wanted my other children to keep my spirit. We all must find ways to survive. I do not want the regime, which has been the cause of all this misery, to win.”

Andy Warhol’s Polaroid of Farah Diba Pahlavi, Empress of Iran, 1976.

But neither does she dream of restoring the old monarchy. Her son, the crown prince, stays active in Iranian politics as a vocal advocate of human rights for his countrymen; she is less directly engaged. Both have called for some kind of secular democracy. “What I dream of,” she says, “is for Iran to get rid of this system. I cannot believe the terrible things I hear.” In the meantime, chance encounters sometimes bring a sense that she is not hated at home. “When I see my compatriots in the streets of Paris, young people who have heard so much nonsense about us, and they come up to me and they hug me, they kiss me, that gives me a lot of courage.”