Friending Aaron Sorkin

In Mark Zuckerberg and the founding of Facebook, the screenwriter behind The Social Network discovered a subject as compulsive and complicated as he is.

In 2008, when Aaron Sorkin read the 13-page proposal for a book that would attempt to detail the birth of Facebook, he stopped at page three and called his agent. It wasn’t the allure of the Internet that captured his attention—Sorkin, who created and wrote 88 episodes of The West Wing and films like The American President, had moderate disdain for the Internet, viewing it as a land of vastly overempowered amateurs. Bloggers had attacked his last TV show, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, in 2007, and he had questioned their credentials, saying “everybody has a voice—the thing is, everybody’s voice oughtn’t be equal…nothing has done more to make us dumber or meaner than the anonymity of the Internet.” What entranced Sorkin, who has always gravitated toward the overlapping and conflicting spheres of idealism and power, was the realization that the invention of Facebook contained all of his favorite themes: the longing for acceptance, the wish for success, the idea that work will give you a home, and that home will solve your problems. But just as Mark Zuckerberg, the computer whiz who dreamed up and developed Facebook as a Harvard sophomore in 2003, was sued by, among others, his original business partner, fellow student Eduardo Saverin, the flip side of the creation story is almost always the destruction of relationships. As Sorkin saw immediately in the proposal, the Facebook saga was the speeded-up version of nearly every business narrative: In just five years Facebook went from a dorm room prank to a global brand worth billions. In that story was the foundation for an even larger, classically American subject—what you lose when you win.

“By the time I called my agent and said, ‘I want to do this,’” Sorkin told me when we met in August, “the book—which, you have to remember, wasn’t written yet—had already been sold to the producer Scott Rudin at Sony.” Sorkin, who is 49, was sitting on the patio at the Four Seasons hotel in Beverly Hills, smoking a Merit cigarette. “I’m only smoking to help you out,” he said, interrupting himself. “It’s a nice transitional sentence: ‘as Sorkin lights another Merit.’” He laughed.

It is precisely this combination of insecurity and self-consciousness that Sorkin imbues all his characters with: They long to be cool, and yet they’re cooler than they think. As usual, he was wearing a suit with a button-down shirt. His blondish hair was streaked from the sun, and he was very tan. When he’s nervous, which is often, he has a tendency to speak like he’s projecting to the back of a theater. “I used to live in this hotel,” Sorkin said as he ordered a Margherita pizza. “I lived at the Four Seasons twice, for a year each time. I’m from the East Coast, and I never wanted to move to Los Angeles. My house in L.A., which is nearby, looks like I bought it with the money I made directing porn. It’s glass and fire and water. It’s a bachelor pad with a jetliner view. It isn’t my taste, but when I looked at traditional houses here, they made me sad, like I was pretending I was living in Westchester [New York], where I grew up. My house isn’t like me—I still feel like I’m staying in a very nice hotel.”

Although they had never worked together before, Rudin—who won an Oscar for best picture for No Country for Old Men and is known for both his excellent taste and his ability to get difficult movies made—agreed to Sorkin’s writing the script. The book proposal had been written by Ben Mezrich, a Harvard graduate who had been successful with another brainy true-life tale—Bringing Down the House, a best-seller about the M.I.T. students who counted cards and beat Vegas at blackjack. That book became the film 21, and at the premiere in Las Vegas, Mezrich met Eduardo Saverin. Saverin wanted to tell his side of the story: how he had funded Facebook from its inception, how Zuckerberg had betrayed him, how their friendship had crumbled. In 2005 Saverin was cut out of Facebook by Zuckerberg and sued, eventually getting an undisclosed settlement. Saverin’s lawsuit was compounded by another lawsuit, brought by Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, twin brothers who had approached Zuckerberg, pre-Facebook, about helping them with their idea, a similar-sounding website called Harvard Connection.

“I wasn’t aware of any of this when I started researching the project,” Sorkin said. Both authors met repeatedly with Saverin and the Winklevoss twins, but Zuckerberg did not cooperate with either the book or the movie. Mezrich’s book, The Accidental Billionaires, which Zuckerberg decried as fiction, was published in 2009 and is sympathetic to Saverin, but sticks to a fairly conventional biographical framework. Sorkin’s script, on the other hand, searches for the reasons and the larger meaning behind the actions of all these men. Instead of focusing solely on how, when, and where Facebook happened (as Mezrich does), Sorkin utilized the legal depositions of the principals—Saverin, the Winklevosses, and, especially, Zuckerberg—and each has their version of events. “There is no ‘truth,’” Rudin explained when I called to ask him about the origins of the project. “And that’s what’s interesting about this story: Truth is always subjective.”

Sorkin’s research unearthed the very first words on what became Facebook—an angry blog post that Zuckerberg allegedly wrote after being dumped by a girl. That blog morphed into a Zuckerberg-invented computer program called Facemash, in which photos of Harvard women were posted online, and compared and contrasted based on their looks. It was a classic misfit’s revenge: If he couldn’t get the girl, he would trash the girl. “I think there’s a subset of nerds who are not the cuddly kinds of nerds we made movies about in the Eighties,” Sorkin said. “These nerds don’t understand why attractive women are still dating the quarterback and not them, why women don’t get that they’re the ones running the universe right now. There’s an arrogance that has alchemized into real nastiness.”

And rage. “First scenes are superimportant to me,” Sorkin continued, lighting another cigarette. “I’ll spend months and months pacing and climbing the walls trying to come up with the first scene. I drive for hours on the freeway. I’m not a germaphobe, but I take six showers a day to get a burst of energy. Especially if things are not going well, I get in the shower and get wet, and get into different clothes and try again. The shower and the car are the two big thinking places for me. For The Social Network, I wanted to imagine the scene with the girl that led to that blog entry. I wanted to have that be the last straw. The girl saying no, the drinking, the blogging, the hacking, the creation of Facemash, all in one night. And then, after that scene, go to the end of the story—the depositions that happened when everything curdled.”

In the finished film, that first scene, between Zuckerberg, played by Jesse Eisenberg, and his soon-to-be-ex-girlfriend Erica Albright— portrayed by Rooney Mara, who was just cast as Lisbeth Salander in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo—sets the tone for the rest of the film. It sings. Throughout his work Sorkin’s dialogue sounds like the rhythms were lifted from a fast-talking Thirties screwball comedy, but the content is something entirely less frothy. As Erica puts it, “Going out with you is like dating a StairMaster.” And later: “Listen. You’re going to be successful and rich. But you’re going to go through life thinking that girls don’t like you because you’re a tech geek. And I want you to know, from the bottom of my heart, that that won’t be true. It’ll be because you’re an asshole.” Zuckerberg’s response is to slag her online, to get his revenge through technology. Zuckerberg’s intellect, as channeled by Sorkin, is like a knife: It is effective but bloody.

When the film’s director, David Fincher, read the opening scene, he was struck by its larger resonance. “It was like Citizen Kane meets John Hughes,” Fincher told me. Unlike many directors, Fincher—who directed Fight Club and, most recently, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button—does not write his movies. And yet he’s attracted to the same subjects again and again: In most of his films, an outsider bumps up against society’s systems and rules. He saw that tension immediately in Sorkin’s screenplay and wanted to move quickly. “I read Social Network in May 2009, and I wanted to film it in the fall. Getting it done quickly seemed important.”

Everything went fast: Eisenberg, who has shown a twitchy intelligence in movies like Adventureland, was cast as Zuckerberg. Andrew Garfield, an English actor who was just chosen as the new Spider-Man, was given the pivotal role of Saverin. Armie Hammer, a great-grandson of billionaire Armand Hammer, plays both handsome, crew-rowing Winklevoss twins. And, after many meetings, Justin Timberlake was cast as Napster cofounder Sean Parker. If The Social Network has a devil, it is Parker, who didn’t make a dime from Napster but who was constantly on the lookout for the next Internet sensation. Zuckerberg was intrigued by Parker, who could read computer code and had both beautiful coeds and hungry venture capitalists in his thrall. “We made Justin audition more than anyone else,” Fincher said. As Parker, Timberlake is just the right mix of slick and craven; he instinctively gets Zuckerberg.

“Sean may be the devil,” Sorkin said at lunch, “but he gets that Zuckerberg is lonely. The common denominator in all my writing is, it’s okay to be alone, if you can find family at work. It’s the romance of being good at your job and being committed to it.” Sorkin paused. It was hard not to think he was speaking about himself. From his first full-length play, A Few Good Men, in 1989, to The West Wing and The Social Network, writing has been, in a real sense, his salvation. “It’s like an on/off switch,” he explained. “Everything can be going well, but if I’m not writing, I’m not happy. When I’m writing well I’m like a different person.” He paused again. “I should be dead,” he said matter-of-factly. “I should be dead five times now. I did things that should have killed me.”

When he lived in this hotel, Sorkin was a crack addict. After A Few Good Men was a hit on Broadway and was sold to the movies, Sorkin, who has a B.F.A. from Syracuse University, flew to Los Angeles to work on the screenplay. Although he initially wanted to be an actor, Sorkin has a gift for dialogue (who can forget Jack Nicholson bellowing, “You can’t handle the truth!” in A Few Good Men), and his first script earned an Oscar nomination for best picture. That success led to other screenplays, and in 1993 he was living in a suite at the Four Seasons, writing The American President and taking drugs.

“I had what they call a ‘high bottom,’” he explained. “My life didn’t fall apart before I got into rehab. I didn’t lose my job or run over a kid or injure anyone when I was high. But the hardest thing I do every day is not take cocaine. You don’t get cured of addiction—you’re just in remission.”

His then girlfriend, Julia Bingham, who worked at Castle Rock, the company that was making The American President, found him an open bed at Hazelden in 1995. “I had no intention of rehab working,” Sorkin recalled. “I just thought it would be good to put 28 days between me and drugs. There were fortune cookie sayings on the walls at Hazelden, and I’m not susceptible to those things. But I’ve never seen anything work as well.”

After his release he joined a small after-care group, which consisted of other addicts who worked in Hollywood. “It was six of us,” he said. “We paid the counselor ourselves. All guys, which was probably better. Early on, if I went to an AA meeting and saw a beautiful woman talking about her hard-partying days, I’d think, Damn—I wish I knew her then. Of the six guys in my after-care group, two are dead. I have my scary moments. When I’m under an unusual amount of pressure, people wonder, Will he relapse? But that’s not it: Opportunity and free time are the biggest temptations. If I feel like I might be able to get away with taking drugs, I’ll make appointments and find ways to be busy.”

In 2001 Sorkin did relapse. “Again, it was a matter of opportunity: Julia [by that time his wife] was away, and I had a window where I could fly to Vegas on a Friday, get high all night, and then return to L.A. the next day. I’d do this three times a year, and it was amazing I never got caught. I was the worst criminal. I had a four-dollar pipe, and the bowl was made of metal. It showed up on the monitor at Burbank airport and they asked to search my bag.” The authorities found a carefully packed bundle of hallucinogenic mushrooms and rock cocaine. “I fainted,” Sorkin said. “When I came to, I was in handcuffs. I was lucky—there are guys serving time in prison for doing less than I did.”

Soon after his arrest, he and Julia separated amicably. “My daughter, Roxy, was only a few months old,” he said. “She’s now nine. I’m dreading the moment she goes online and reads about my arrest. But at least I’ll have credibility with her when it comes to drugs. I won’t be some old guy who doesn’t know how to have fun.

“When I first got sober, my biggest fear was, Am I going to be able to write without cocaine? In the past my dealer would come over, and I’d do drugs all night long and I’d write high. I was worried that I couldn’t write with the sun out.” After rehab, to test himself, he took a two-week job polishing dialogue for a Michael Bay movie called The Rock. “I was just writing quips for Sean Connery and Nic Cage, but the first time I wrote in the daytime, I was so proud. Now my firewall is Roxy. I’d let her down if I relapsed.”

The solo nature of Sorkin’s drug taking somehow mirrors Zuckerberg’s trancelike state at the computer: They would seem to share a kind of brilliant isolation. Even now that he is sober, there’s something solitary about Sorkin. “I don’t feel like a nerd,” he explained, “but I think I understand them. Sometimes I literally don’t know what to do with my hands. I know what I used to do, and I don’t know what to do now. At parties I stay where the crowd is. I don’t want to get into trouble off by myself.”

In his dark, cozy office at Warner Bros., Sorkin has hung his heroes on the wall. Next to mementos from his TV shows—the door to the Oval Office from The West Wing, an intentionally crumbling neon sign from Studio 60, another door from his first show, Sports Night—are framed portraits of the playwrights Clifford Odets, George Bernard Shaw, Tennessee Williams, and Arthur Miller. “Madonna got in touch with me a while ago,” Sorkin said. “I think she wants me to be Arthur Miller to her Marilyn.” He never made the date.

“This came from Maureen,” he said, pointing to a framed New Yorker cartoon. Sorkin had a long relationship with New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd, and they remain close. In the cartoon a man is wearing a tuxedo, preparing for a big night out, while a woman admires him. The caption reads come on. you’ll have fun. all the men will respect you and all the women will love you. He sighed. “Maureen seemed to understand me so well.”

Sorkin sat in a gray leather club chair, which matched his gray suit. In his office, which is lived-in and full of leather and mahogany, he seemed like he was back on the East Coast. “All my heroes wore coats and ties to work,” he said, looking around the room. “What happened to men wearing hats? Maybe I should bring back hats.”

Sorkin’s affection for the glory days of show business began when he was a child growing up in Scarsdale. His father (a lawyer), his mother (a fourth-grade teacher), and his two siblings (now both lawyers) were not particularly theatrical, but Sorkin used his allowance to take the train to Manhattan and sneak into plays. “I’ve seen the second act of everything many, many times,” he said. “The ushers started to recognize me, and they’d find me a seat.”

During college he tended bar at Broadway theaters and wrote most of A Few Good Men on cocktail napkins during the first act of La Cage aux Folles. “For 500 nights in a row,” Sorkin added as he lit another Merit. Before he was holed up at the Four Seasons, writing The American President and taking drugs, he wasn’t particularly intrigued by TV. “I’d write very, very late into the night, and to keep me company I’d watch ESPN’s SportsCenter,” Sorkin recalled. “I thought it was the best-written show on TV. And SportsCenter seemed like such a fun place to work—you’d meet your best friend there, you’d meet your girlfriend there.”

Sports Night, which aired on ABC from 1998 to 2000, started a method of writing that is unique to Sorkin: When he was running his three series, he wrote every episode. “When I create a TV show, it’s so that I can write it,” he said. “I’m not an empire builder; my writing staff is usually a combination of two kinds of people—experts in the world the show is set in, and young writers who will not be unhappy if they’re not writing scripts. A lot of members of the Writers Guild are not happy that I write all the episodes. But writing is something that I do by myself.” When Sports Night and The West Wing were on the air simultaneously, Sorkin would write the half-hour comedy Friday through Sunday, and then concentrate on the hour-long drama Monday through Thursday. “Being up against the wall seems to work for me,” he said.

Perhaps because there’s not the same weekly deadline, movie scripts take him longer. Stuck on a bulletin board in his office are colored index cards that spell out the intricate structure of The Social Network, which alternates between depositions and the actions the depositions describe. Despite the volume of language in Sorkin’s script, Fincher had a way of making the snap-crackle-pop dialogue sound like regular conversation. “For the first scene,” Fincher told me, “I did 90 takes. I wanted to knock the ‘acting’ out of them. The actors should toss off the words like it’s their phone number.”

That technique is perfect for Sorkin’s style, which can be theatrical. “With most of my work, I haven’t needed to worry about the so-called truth,” Sorkin continued. “Our White House on West Wing was not like the real White House, but it needed to have the appearance of reality. With Social Network I was forced to care about the facts because there were legal consequences. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that everyone in this story believed their own story. They were alone in their conviction that their story was the only accurate one.” He paused. “That’s human nature. We all want love and respect,” Sorkin said. “That dream is the key to it all.”

Friending Aaron Sorkin

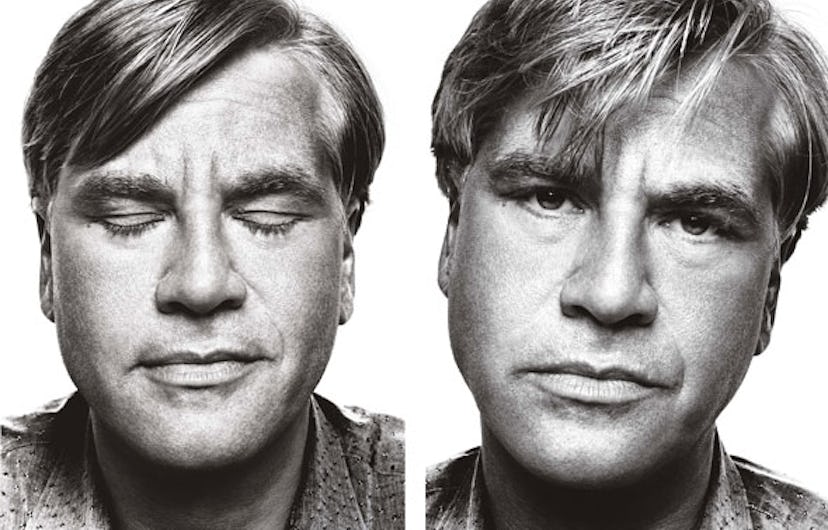

Aaron Sorkin

Aaron Sorkin

Justin Timberlake plays Sean Parker, cofounder of Napster and a Facebook executive. It was reportedly the most difficult role to cast; Timberlake auditioned multiple times before getting the part.

Andrew Garfield plays Eduardo Saverin, cofounder of Facebook. Garfield has been cast as Peter Parker in the 2012 version of Spider-Man.

Rooney Mara plays Erica Albright, the “Helen of Troy of Facebook,” who rejected Mark Zuckerberg, causing him to create a Facebook precursor as a form of revenge. Mara has been cast as Lisbeth Salander in David Fincher’s The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.

Jesse Eisenberg plays Facebook cofounder Mark Zuckerberg.

Armie Hammer plays twins.