Czar Power

A family fortune, an A-list charity and ownership of the London Evening Standard have made Evgeny Lebedev Britain’s hottest Russian import.

Mikhail Gorbachev sang right there,” Evgeny Lebedev says emphatically, pointing to a patch of flattened grass on his back lawn, which still bears the outline of a marquee that has just been removed. A few nights earlier, the Raisa Gorbachev Foundation, of which Lebedev is chairman, held a charity gala here at his family’s estate just outside London. Some 350 guests listened as the former president warbled a love song in memory of his late wife. Now in its fourth year, the gala has become a top-drawer event in London’s glittering summer social season, and Lebedev himself, just 29, has gained prominence along with it.

Unlike most of his fellow Russian tycoons who base themselves in London, Lebedev has spent most of his life in Britain. He was eight when his father, Alexander, took a job at the Soviet embassy. Unbeknownst to most people, including his son, he wasn’t a diplomat but a KGB spy. Following the collapse of Soviet Communism, in 1992, the family returned to Moscow, where Alexander later bought the National Reserve Bank, nabbed 30 percent of Aeroflot and made other investments that earned him billions. He has since been dubbed “the spy who came in for the gold.”

The fortune has made both father and son sought-after figures in British society. The lawn where they pitched the aforementioned tent is on the grounds of Stud House, a mansion within the Queen’s parkland of Hampton Court Palace, which the Lebedevs acquired in 2007 for about $16 million. While Alexander visits occasionally from his home in Moscow, the place is used mostly as a weekend retreat by Evgeny, who lives in central London.

Further cementing the family’s status among the English establishment, Evgeny and Alexander became the country’s newest press barons in January, with their surprise purchase of the London Evening Standard, one of the city’s oldest and most venerable newspapers, from Lord Rothermere. The close of the deal coincided, of course, with the world financial meltdown, which hit Russia’s so-called oligarchs particularly hard. Forbes recently reported that Alexander lost around half of his fortune, which had been estimated at $3.1 billion in 2008—a claim the gentleman refuted and threatened to sue the publication over.

Either way, Alexander surely has some rubles left. Though the price of the Standard was reported to have been just one pound (a figure its new editor, Geordie Greig, disputes), its new owner assumed the paper’s considerable debts and estimated annual losses of around $30 million. Although Alexander is chairman, he put the paper’s shares in Evgeny’s name and has apparently left him in charge. As senior executive director, Evgeny spends two days a week at the Standard’s offices, overseeing the business side of the operation.

Only a few years ago, Evgeny seemed to be making a name for himself as a classic spoiled playboy. Once described in British GQ as “a snake-hipped vodka-drinking Soviet,” he was named Britain’s third most eligible bachelor by Tatler magazine in 2006 (after Sam Branson and Russell Brand), and he has been linked to a succession of models, pop stars and actresses, including Sophie Dahl, Geri Halliwell and, currently, Joely Richardson.

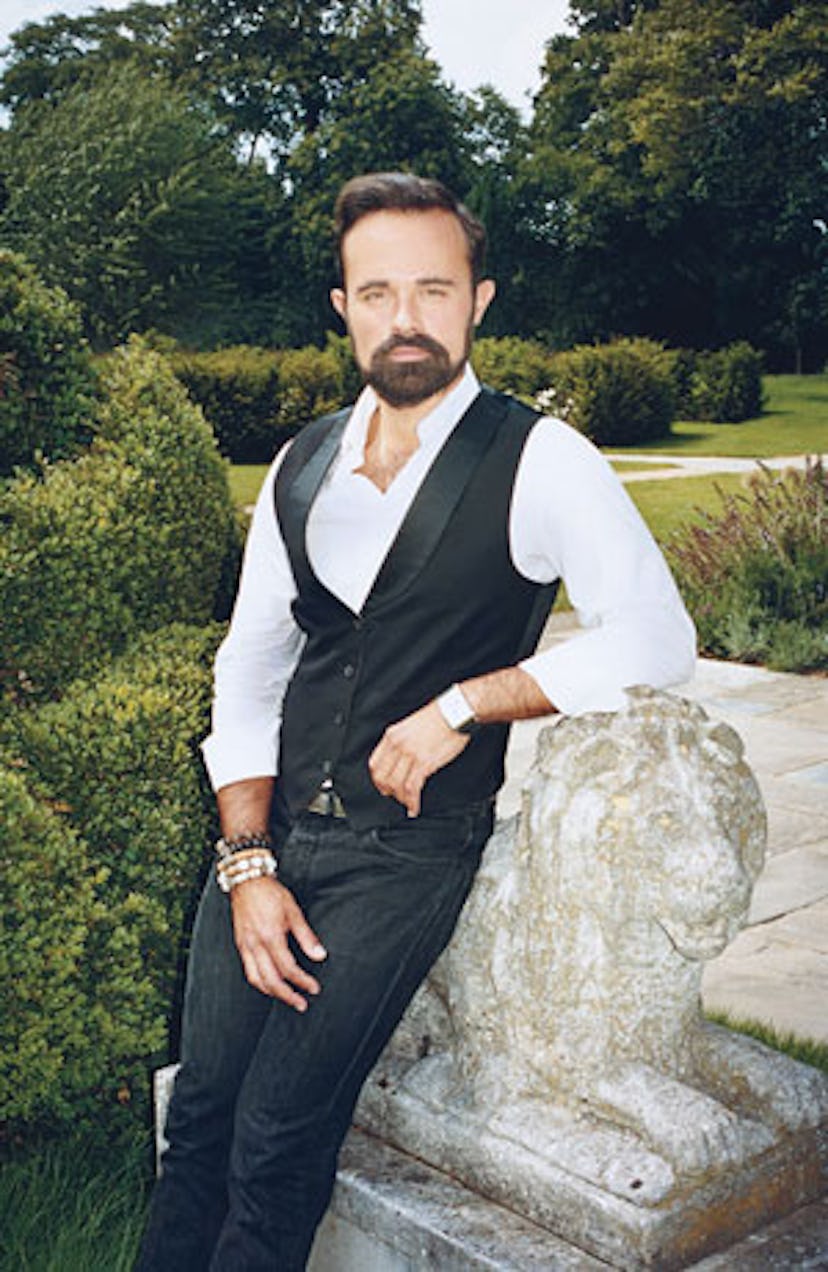

That image, however, seems hard to square with the man receiving me on this June afternoon. With a meticulously clipped dark beard that makes him resemble a 19th-century czar, he has intense brown eyes and a somewhat solemn air. But he is coolly attired in jeans, a white shirt, a Martin Margiela pinstriped vest and Lanvin sneakers.

“Evgeny had some wild years, but those are well and truly over,” says longtime friend Jonathan Rutherford Best, a prominent London event planner. “It’s been very interesting to see where he has been channeling his good fortune, which is into philanthropy.”

It quickly becomes apparent that Evgeny has some very sharp opinions, particularly about Russia’s power structure. “They are all quite gray and faceless,” he says, referring to the country’s political and financial leaders, as a butler serves us mint tea in a paneled sitting room. When asked about his fellow London-based Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich, he is dismissive. “I don’t know him, but he just seems like a person who’s not particularly interested or interesting…. No one ever hears him speak or say anything. He’s not engaging—there’s no life there, if you know what I mean.”

Still worse, he continues, is Russia’s strongman, Vladimir Putin. “When we think of him, we think of him topless, running around, flexing his muscles,” he says, referring to widely published photos of Putin sans shirt. “This is the image most people have of Russia,” he laments. “We are viewed as barbaric, sort of backwards.”

Evgeny’s perspective on Russia and the UK stems from his early education. His parents broke the rules when they pulled him out of the Soviet embassy academy and enrolled him in a Church of England school. “It was thought highly inappropriate at the time for Soviet children to go to capitalist schools, but my parents sort of snuck me out,” he explains. “It was a very pleasant experience because I was very much accepted by the other pupils.” Though Evgeny accompanied his parents back to Russia in 1992, he returned to London a few years later to continue his studies, at the London School of Economics and Christie’s.

While a sizable community of wealthy Russians have settled in London, they have not integrated into society, Evgeny observes. “They keep to themselves, yet they complain the English are snooty and they are being kept out,” he says. “Actually, to be accepted when you come to a new country, you need to learn the language and the culture. There’s no secret. The funny thing is, the things they really want to be accepted in are Ascot and the so-called season. It’s a bit sad, I think.”

Still, the challenge of getting Russians to integrate pales next to the task of reviving the Standard. Negotiations to purchase the paper began in secret in spring 2008, when Greig, a friend of the Lebedevs who was then editor of Tatler, confided to them that Lord Rothermere would be interested in selling. Reportedly, Alexander had harbored a fondness for the paper since his spy days, when one of his duties was to peruse it every day for news to send to the Kremlin. And he has publishing experience as co-owner (with Gorbachev) of Novaya Gazeta, Russia’s only independent newspaper.

Greig oversaw a revamp of the Standard, which was launched on May 11. Along with bolder, more colorful graphics, the paper now offers increased features-oriented coverage. It is still too soon to know whether the changes will lead to success, but media watchers in England seem to be cautiously optimistic. “They have been making a valiant attempt to modernize the paper by broadening their coverage and bringing in younger, fresher writers,” says Stephen Brook, press correspondent of The Guardian.

In addition to his role at the paper, Evgeny has a host of other business interests, including fashion, hotels and restaurants, which he discusses as his driver speeds us back to London. “I seem to get involved with the most difficult businesses there are,” he says. Currently he has plans to launch a Russian edition of the alternative fashion magazine Dazed & Confused. (Coincidentally, Dasha Zhukova, Abramovich’s girlfriend, has just become editor of the biannual British fashion magazine Pop.) Meanwhile, he owns Wintle, a bespoke men’s wear line based in London and known for its precise yet quirky tailoring; a hotel, Palazzo Terranova, which is housed in a 17th-century Umbrian villa; and a majority stake in one of London’s most fashionable restaurants, Sake No Hana, which is clearly why, as we pull up at close to 4 p.m., the staff is at attention and the kitchen has remained open to serve us a late lunch. After excusing himself to take a phone call, Evgeny returns to our table and shares some news: “I have a brother born today.” Just hours before, he explains, his father’s girlfriend gave birth in Moscow. If it is traumatic for him to have his first sibling—and, it must be said, to have the prospect of his inheritance being halved—he does not show it.

Alexander, 49, separated in 1998 from Evgeny’s mother, Natalia, who works as a microbiologist in Moscow, where she earns $300 a month, Evgeny notes (a living supplemented by Alexander). Elena Perminova, Alexander’s girlfriend of several years, is a 22-year-old former model who once posed nude in Russian Playboy. She recently told British Vogue that the couple prefer the simple things in life. One of their favorite pastimes is to cut holes in the ice on the Moscow River and fish for bream.

While Evgeny says he “gets along well” with Perminova, he notes that most of his friends are his father’s age. “Which may be quite Freudian,” he adds with a laugh. The age difference also extends to Richardson, 44. Lebedev prefers not to discuss the relationship, other than to say, “I’ve learned a lot from her and her whole family. They are extraordinary.”

He is a bit more forthcoming about his father. “He’s quite remarkable,” Evgeny says. “We’ve grown much closer over the past few years. He’s got a very unconventional, open mind.” His first inkling that his father was a spy, he recalls, came while he was still a boy, after he found a military- looking medal in a desk drawer. But being a spy in London was hardly as glamorous or dramatic as being James Bond, he says, almost with a trace of disappointment. It’s much more of a desk job, he insists, almost dull. “Unless you’re Alexander Litvinenko,” he adds, referring to the former spy who died mysteriously of poisoning by rare polonium-210 after lunching in another London sushi bar two years ago.

Fortuitously the discussion comes just as a glistening platter of sashimi is set before us. Reading my mind, Lebedev assures me the tuna is not radioactive. He picks up his chopsticks and digs right in.