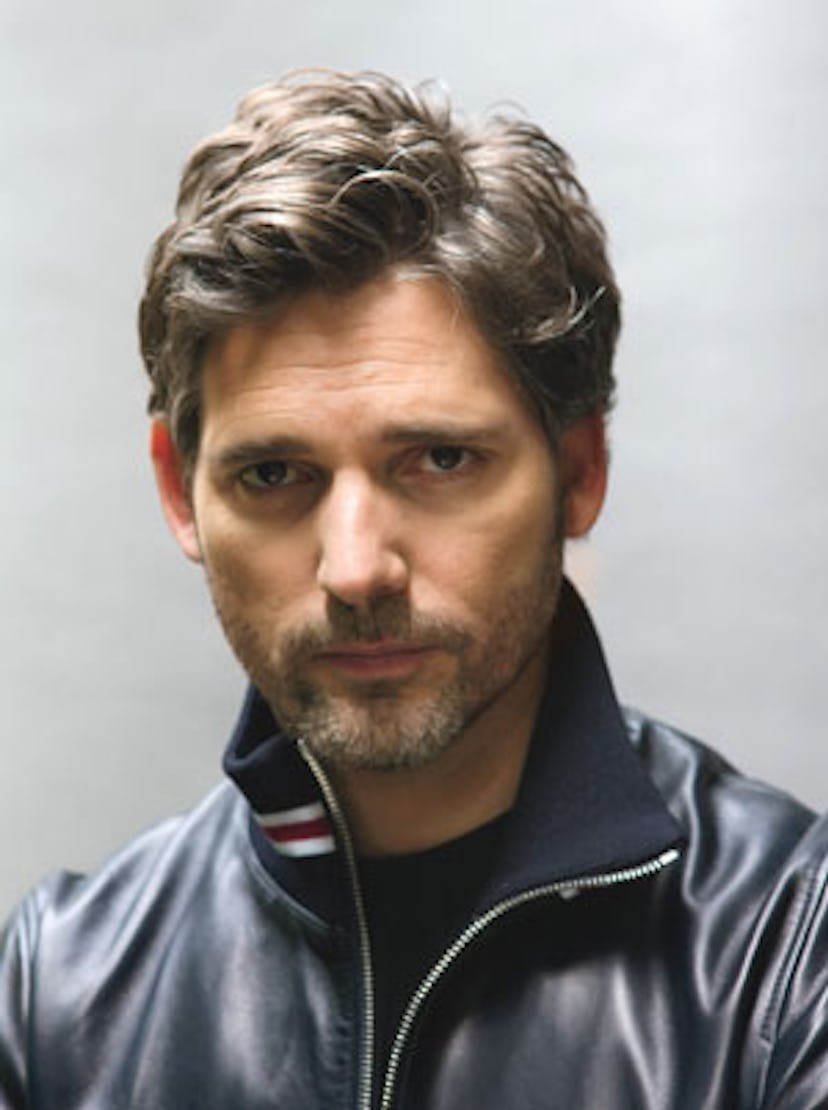

Eric Bana

After a string of smoldering dramatic roles, former stand-up comic Eric Bana learns to laugh again in Funny People.

Eric Bana, the Aussie actor best known for his serious, interior performance as an Israeli covert operative in Steven Spielberg’s Munich, is an unlikely writing partner for Judd Apatow, widely considered to be a genius of lowbrow comedy. But in Apatow’s new movie, Funny People, Bana took it upon himself to make a key—and ultimately brilliant—change to the script.

“My character was originally American,” says Bana in Beverly Hills the day of the Los Angeles premiere of Star Trek, in which he’s almost unrecognizable as the tattooed space thug Nero. “I just thought I could make it funnier if I were Australian.”

In Funny People Bana’s Clarke is a loudmouthed member of the transglobal corporate ruling class. He lives in a fancy San Francisco suburb with his lovely wife (played by Apatow’s wife, Leslie Mann) and their overachieving young daughters (the girls speak Mandarin at the dinner table), but sees no problem with getting a massage-parlor “rub and tug” while traveling on business in Asia. The character is, deliciously, a Grade-A jerk with a megaphone voice, and Bana plays him broader than the Australian outback.

“I read the script, and my brain went crazy,” says Bana, who at 41 has gray streaks at his temples and is easing into midlife like a hunkier Richard Gere. “I know these guys. I know exactly how they work. I know how they behave. And I know how loud they are.”

In a scene that threatens to steal the movie from star Adam Sandler—his character is a stand-up comedian who believes that he’s dying of cancer and tries to reconnect with Mann, a former flame—Clarke shows the glum American and his joke writer and assistant (Seth Rogen) how Australian extroverts indulge their national passion for televised “footy,” or Australian Rules football, with hilariously exuberant demonstrations of physical aggression.

“There is a half-hour version of that scene where I don’t draw breath,” says Bana, who is considerably more subdued in person. “We went through 3,000 feet [of film]. It was me just going insane, tackling them and showing them how to kick. I just went absolutely off my head.”

“At one point, he was also singing ‘When the Saints Go Marching In’ because the [St. Kilda] Saints are his team,” recalls Apatow during a break from postproduction on the film, which opens July 31. “It made us laugh so hard. I need to turn it into a 10-minute DVD extra.”

While Bana, who lives in his native Melbourne with his wife and their two children, is milder than Clarke, he was still a favorite on the set, says the director. He’s the affable jock who can also scrimmage with the nerdy Apatow bunch on their own turf: off-the-cuff comedy. “We were all depressed when he left,” says Apatow. “He isn’t working from the emotional life of an insecure, neurotic comic. He’s more comfortable in his skin than any of us, but he still has a wicked sense of humor.”

Apatow first took serious notice of Bana in Munich, and he did research on YouTube into the actor’s comedy background, which is little known on this side of the Pacific. Bana joined the stand-up circuit in Melbourne some 20 years ago as a rank amateur with no experience apart from amusing his mates with impersonations. Before that, he says, he’d never thought of studying acting—“to me, going to drama school would have been like going to NASA”—but then, he didn’t have any other professional plans to pursue.

“Stand-up came out of three things,” Bana explains. “Frustration, necessity and arrogance. I didn’t have a great career ahead of me in anything. Someone literally said to me, ‘You should try stand-up,’ and took me to a venue. One guy onstage was pretty good, and the other three just sucked. I was like, ‘They’re getting paid? I think I want to give this a try.’”

Over the next decade, Bana built a career that eventually led him to Full Frontal, an antipodean Little Britain–type comedy sketch show full of boisterous blowhards with accents that are nearly indecipherable to foreigners. Four years later, in 1997, Bana became a marquee name with The Eric Bana Show Live, which highlighted the actor’s knack for caricaturing Tom Cruise and Arnold Schwarzenegger, among others. (Fortunately, he has yet to encounter any of his early targets in the flesh.)

This belly-laugh résumé unexpectedly led Bana to the grittiest and arguably best role of his career when he was cast as notorious Australian convict Mark Brandon Read in the 2000 movie Chopper, directed by Andrew Dominik (who later made The Assassination of Jesse James, with Brad Pitt). “We read every working Australian actor who was even vaguely appropriate for the part,” says Dominik, who notes that Read, who claims to have murdered 19 men and wrote a best-selling memoir from prison, himself suggested Bana after seeing him on Full Frontal and noting a physical resemblance. “Eric just did Read really well, and after working with him for a day, I knew he was the guy. It was very difficult to get people to finance the film with Eric, though. It was like casting Seth Meyers in Raging Bull.”

Bana says that the transition wasn’t hard, and he dismisses the notion that acting is a “shrouded mystery” distinct from what a comic does to create a persona. “If you can jump up onstage and make people laugh, shouldn’t you also be able to inhabit a character?” he asks, as if this were a commonsense observation. “To me it wasn’t like there was a Grand Canyon between the two. I never saw any reason why you wouldn’t attempt that next step.”

Chopper proved to be Bana’s passport from the provinces to the Hollywood studios, and he immediately found ensemble work alongside top-notch actors in Black Hawk Down and Troy. While he has never socialized with Hollywood’s Aussie Bunch—Nicole Kidman, Russell Crowe, et al—Bana says he still benefited from a similar career trajectory. “By the time an American audience sees us, we’ve usually got a body of work already behind us,” he explains. “We’ve made all of our embarrassing mistakes behind closed doors. If I had the same early career here in America, you wouldn’t have bought me as the guy from Saturday Night Live suddenly doing Chopper.”

Ang Lee offered Bana his first ride in a starmaking vehicle when he cast the actor in Hulk. The movie bombed with critics and audiences, but, as Bana once noted in an interview, Spielberg got the idea to sign him for Munich after seeing the “sensitivity” he brought to the role of Bruce Banner. And in Hollywood, carrying the weight of a three-hour Spielberg epic changes everything.

“After I saw it, I turned to my wife and said, ‘That’s the greatest movie star I’ve ever seen,’” recalls Apatow, who liked Munich so much that he wrote a mention of it into the script of Knocked Up—it’s cited in one scene by the film’s characters as a rare example of what Apatow calls a “kick-ass Jewish revenge movie.” Bana was equally in a class apart, says Apatow: “It was like seeing Steve McQueen for the first time.”

Since Chopper, Bana has kept a steady pace of one film annually, until this year, when in addition to Star Trek and Funny People, he stars in The Time Traveler’s Wife. The three projects could hardly be more unlike one another. In The Time Traveler’s Wife, Bana is born with a genetic tendency to slip back and forth through time. Eventually he intersects with his wife, portrayed by Rachel McAdams, at the proper year to consummate their romance, which, cleaving to the conventions of an estrogen weepie, is a timeless love for the ages. The film panders to its intended audience with a conceit: The time traveler’s clothes don’t travel with him. The movie is sure to trigger hot flashes when Bana appears onscreen repeatedly in his beefy altogether.

“I don’t know if anyone wants to see a 40-year-old man’s ass,” he demurs when asked about the nudity, modestly undervaluing his personal assets, or perhaps just failing to fully appreciate how differently niche audiences have responded to his varied film work. He recounts, for instance, being surprised at a Star Trek screening for U.S. troops in Kuwait, when the men gave him shout-outs for Black Hawk Down, Munich and Troy while the women swooned over last year’s The Other Boleyn Girl.

Bana’s other recent film will likely appeal more to the testosterone crowd. Love the Beast, which he directed and produced, is a sentimental portrait of Bana’s first automobile, a 1974 Australian Ford Falcon coupe muscle car he nicknamed the Beast, which he still drives after 25 years. Jay Leno and Dr. Phil appear in the documentary to help tease out the true significance of the Beast as the center of a world of masculine camaraderie Bana shares with his lifelong friends. “There’s so much focus and social activity that comes with owning this car,” Bana explains. “It’s that old thing of women bond by talking and men by doing. Over my lifetime, the car had actually transcended the fact that it is a car. It has become a venue.”

Love the Beast screened at the Tribeca Film Festival to largely positive reviews, though it doesn’t yet have American distribution. Bana boasts that it has already become the second-highest grossing non-Imax domestic documentary ever in Australia (after 2007’s Bra Boys)—a distinction some might find almost comically modest. Nonetheless, it’s a pleasing one for an actor who has steadfastly clung to his homeland despite his Stateside success, and he praises the virtues of living in a country with a muted celebrity culture.

“It’s not as crazy as here; it’s more sporting-based than based on the arts, fortunately for me,” says Bana of comparatively paparazzi-free Melbourne. “Once the footy season is under way, it wouldn’t matter who you are. Trust me.”