Wild Wolfe

One of America’s first female decorators, Elsie de Wolfe was also prewar Europe’s great party animal.

On an unseasonably chilly evening in July 1939, upwards of 700 men and women in white tie and gowns gathered on the grounds of Villa Trianon in Versailles. The occasion was the second annual Circus Ball given by the storied decorator and society figure Elsie de Wolfe. Lady Mendl (as de Wolfe preferred to be called after she wed Sir Charles Mendl, in 1926) had organized a suite of performances to amuse her guests, who included Cecil Beaton; Coco Chanel; Clare Boothe Luce and her husband, Henry Luce; several members of the Rothschild family; and no shortage of titled aristocrats. Among the night’s bedazzlements were a team of white Lipizzaner horses in jeweled harnesses and a mini-parade of trained ponies and dogs led around a ring by de Wolfe herself, who was dressed in Mainbocher and still nimble at age 81. Just two months later, Adolf Hitler would invade Poland, making de Wolfe’s over-the-top fete the very last such legendary ball of that era.

Talented, tenacious, and absurdly energetic, de Wolfe was one of America’s first female decorators, a tastemaker who helped cast off the public’s infatuation with heavy, embellished Victorian decor in favor of lightness, simplicity, and a more functional approach to living. Her 1913 book, The House in Good Taste, is full of pronouncements that still resonate today. “I believe in plenty of optimism and white paint, comfortable chairs with lights beside them,” she wrote. But it is her less explored role as a central social figure among Paris’s international set that is the subject of Elsie de Wolfe’s Paris: Frivolity Before the Storm (Abrams), a new book by Charlie Scheips, out in October.

A social historian and curator, Scheips focuses on de Wolfe’s later years. After her marriage, at age 68, Lady Mendl spent less time on her decorating business, while she burnished her reputation as the best-known American hostess in Europe. It was the discovery of a trove of unpublished photographs, most of them of de Wolfe’s two Circus Balls, that sparked Scheips’s interest. The images ** included not only candid party shots but behind-the-scenes documentation of the extensive preparation that went into each party: We see a painter sprucing up the circus ring, gardeners icing the champagne, and a chic de Wolfe, in a silk head scarf and her signature triple-strand pearl necklace, feeding the Shetland parade ponies.

De Wolfe’s style of entertaining in Paris in the late ’30s, argues Scheips, has never been replicated. “The dresses weren’t borrowed, there was rarely the pretense of charity, and the parties lasted until dawn,” he says. “It’s not like the galas of today, where everybody goes home at 10 p.m. with a gift bag.”

But for all the fabulousness, de Wolfe was a pioneer. Born in 1858 in New York to a family that was educated but not well-off, de Wolfe was, in her own words, “an ugly child”—albeit one with a keen aesthetic sensibility. One of her earliest memories, recounted in her 1935 autobiography, After All, was of arriving home one day to find new drawing room wallpaper; the pattern struck her as so repulsive that she felt physically assaulted, like “something terrible that cut like a knife.”

As a teenager, she was sent to live with an aunt and uncle in Scotland for “finishing.” She later returned to New York, where she found work as an actress and met Bessie Marbury, her companion for the next 40 years. Hailing from one of Manhattan’s most prominent families, Marbury enjoyed a comfortable fortune, and the two women set up house together on Irving Place in what was then known as a “Boston marriage.” While Marbury built a successful career as a literary agent, de Wolfe decorated their home to her own rapidly developing tastes. It soon became the scene of one of the city’s most exciting salons. As de Wolfe recounted, when her stage career hit a standstill, it was Marbury who suggested, “Why not go ahead and be America’s first woman decorator?”

She began with the Colony Club, the country’s first exclusive private club for women, becoming an overnight design darling with her introduction of a lighter palette and an abundance of chintz—a marked departure from the dark and stiff decor of men’s clubs. One job followed another, eventually leading to the ultimate prize: the family rooms of Henry Clay Frick’s recently built mansion on Fifth Avenue. The steel magnate gave de Wolfe a hefty commission on everything she purchased for him; she took home more than $1 million. Scheips’s book includes a portrait of de Wolfe by Baron Adolph de Meyer taken around that time, showing her in a white gown and fur stole, a jeweled choker on her neck, looking very much the society doyenne.

In 1903, on a summer trip to Paris, de Wolfe and Marbury discovered Villa Trianon, a deserted Louis XV pavilion on the grounds of Palace of Versailles; its restoration and redecoration became de Wolfe’s lifework and continued even after “the bachelors”—as Marbury and de Wolfe called themselves—had drifted apart and de Wolfe shocked le ** Tout-Paris with her surprise marriage. (Scheips points out that by wedding Sir Mendl, a British diplomat, de Wolfe gained not only a title but also tax-free status in France.)

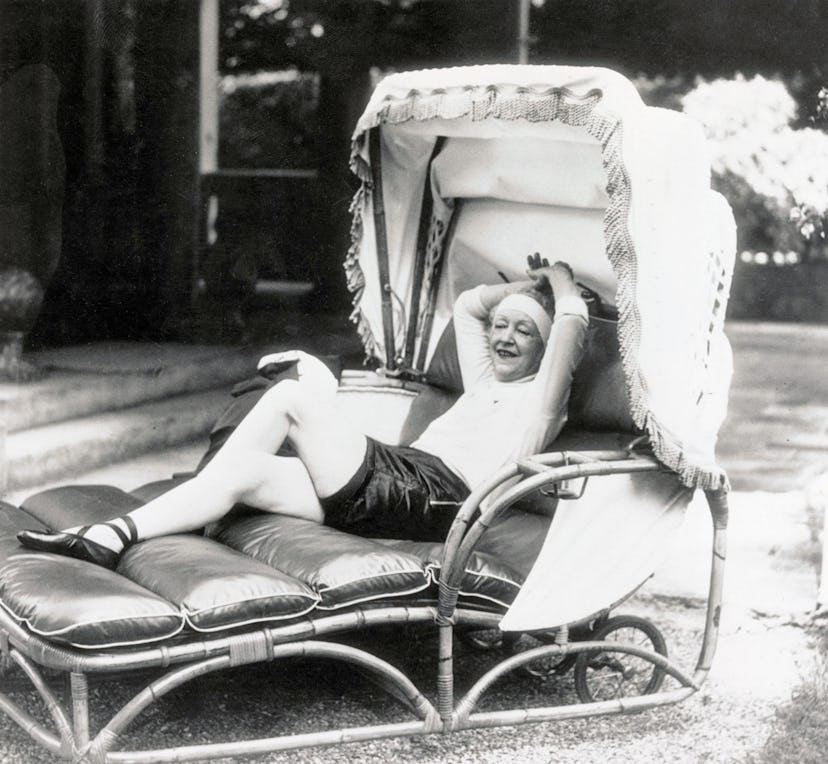

“Elsie had an indomitable spirit,” observes Scheips, pointing to her ability to reinvent herself from actress to decorator to volunteer nurse (she received a Legion of Honor award for her services during World War I) to society matron. Although she was born before the Civil War, she was in many ways a contemporary woman. She made her own fortune through hard work, ingenuity, and networking, and she was, if not openly lesbian, unapologetic about her relationship with Marbury. (never complain, never explain was one of the embroidered mottoes on her signature pillows.) She practiced yoga, tried plastic surgery, and understood the power of branding: Her logo was a wolf with a nosegay in its mouth. And long before Martha Stewart, de Wolfe taught homemakers how to run their households with savoir faire. As Scheips notes, in her influential columns de Wolfe advised women to buy good reproduction furniture, give “great dignity” to rooms by adding “molding at a few cents a foot,” and entertain according to a few cardinal rules: “Plates should be hot, hot, hot; glasses cold, cold, cold; and table decorations low, low, low.”

Of course, whether de Wolfe’s embrace of frivolity in a darkening Europe was evidence of her insensitivity and political obtuseness or a heroic defense of civilized life is up for debate. (Reviewing de Wolfe’s memoir, one critic wrote: “As propaganda for the social revolution, this book should be invaluable.”) Scheips recounts how, after discovering the photographs of de Wolfe’s extravaganzas, he showed them to the former Vogue fashion editor Babs Simpson, still alive at age 101. “Where would one ever wear these beautiful dresses today?” she said to him in amazement.

Photos: Wild Wolfe

Bernard Boutet de Monvel’s painting of de Wolfe, 1936. Bernard Boutet de Monvel, Lady Mendl (1936), Oil on canvas, Private Collection, courtesy of Stéphane-Jacques Addade, photograph ©Jacques Pépion.

The sunroom at Villa Trianon, 1930s, formerly the dining terrace. ©Condé Nast.

Arriving at Trianon for de Wolfe’s first Circus Ball: an unidentified guest, Paul Morand, Coco Chanel, and Serge Lifar (from left). Courtesy of Roger Schall ©Jean-Frédéric Schall.

De Wolfe practicing yoga. Courtesy of Charlotte Moss.

Acrobats at de Wolfe’s 1938 Circus Ball. Courtesy of Roger Schall ©Jean-Frédéric Schall.

William Ranken’s painting of de Wolfe’s bedroom at Trianon, 1920s. Courtesy of Charlotte Moss.

Bessie Marbury and de Wolfe, “the bachelors.” Courtesy of Roger Schall ©Jean-Frédéric Schall.

De Wolfe, relaxing at home at Villa Trianon, Versailles, 1935. © Bettmann/Corbis.