Why Elliott Smith’s Either/Or Hurts as Good Today

On its 20th anniversary, with the release of an expanded reissue, the late singer’s third album feels as powerful as ever.

There’s now a bar where Figure 8 used to stand. Or, not Figure 8, exactly, but the red-and-blue mural along Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles that was the backdrop for the Autumn De Wilde-shot portrait that covered Elliott Smith’s fifth and final studio album. That mural marked the site of the Solutions Audio-Visual Repair Shop; with Smith’s death by apparent suicide in 2003, it also became a public site of mourning. Now it is a place called Bar Angeles, which surely must be a reference to the track off the late singer’s 1997 album, Either/Or.

The strangest thing has always been sharing Elliott Smith. Discovering Smith has been something of a rite of passage for certain young people, but in spite of the vast fan base he cultivated during his decade-and-a-half-long career, the music he made is so intimate, so intensely personal, it asks individual, rather than communal, engagement. (This makes a public mourning site a curiosity.) Nowhere is this better exemplified than on Either/Or. Smith’s third studio effort is a quietly devastating record and, paradoxically, the one that catapulted him into the hands of a major label (he signed with Dreamworks the next year) and onto the stage of the 1998 Academy Awards. But when it was released, he was still small-ish time, an L.A. transplant via Portland on the cusp of making it big.

Either/Or turned 20 last month; this Friday, on the occasion of its anniversary, Smith’s one-time label Kill Rock Stars, will release a remastered, expanded edition of the record in collaboration with Larry Crane, a recording engineer who worked with the musician on his fourth album XO and “Miss Misery,” the Good Will Hunting theme that earned Smith an Oscar nomination. Smith’s third album was the articulation between his earliest, lo-fi work (Roman Candle and his self-titled sophomore album) and the major-label records XO and Figure 8. It came just before Good Will Hunting, before the Oscars, and before “he wasn’t just our little Elliott treasure anymore,” Crane explained in a recent interview with the New York Times. “We had to share him with the world.”

I was barely a whisper of a human when Smith released Either/Or in 1997, but in 2006, when Metric’s Emily Haines recorded a cover of “Between the Bars,” I was a seventh grader, still adjusting to a recent move abroad. A friend, who I always considered my cooler twin from back home—we had the same hair, the same musical pretensions—sent me a YouTube link, likely accompanied by many pre-emoji analogue emoticons. Immediately, I devoured the Metric cover—several times over—and found my way to the original. It may have been all I listened to for the rest of the year.

Like everyone who finds their way to Elliott Smith, it felt like he was writing about/for/through me. My favorite time to write remains the period after the rest of the city goes to sleep and before they wake up again—twilight hours that still sound like the gentle, 6/8 lilt of “Between the Bars.” And once he has you, he always will. Smith continues to resonate for everyone from Frank Ocean, who credited him in the liner notes of Blonde, and Sadie Dupuis of Speedy Ortiz, who cited the impact of Smith’s early noise outfit Heatmiser on her band.

“I’m not interested in making ‘Elliott Smith Records’ over and over again. I’d be really happy if I could write a song as universal and accessible as ‘I Second That Emotion,’” Smith told Spin in 1999. “It’s a big game to play, trying to make something that’s mainstream enough and still human.”

Either/Or is a big album about the tiniest, near-invisible things. It throbs with a dull ache rather than stabbing you with sadness. And, though suffused with melancholy, it never wallows. With its allusions to depression and addiction, it is impossible to disentangle from the apparent suicide of Smith, who has become something of an avatar for grief, but songs like “Say Yes” are some of the most quietly optimistic around, while “Pictures of Me” is bursting with barely contained anger, the closest Smith ever gets to howling.

Gus Van Sant heard Either/Or while he was making Good Will Hunting. “Between the Bars,” “Angeles,” “Say Yes,” and “No Name #3” (from Smith’s debut, Roman Candle) all made their way onto the soundtrack before the director asked Smith to write an original song to tie it all together. So “Miss Misery,” then a work in progress, became the lynchpin of the soundtrack. It went on to earn Smith his first and only Academy Award nomination.

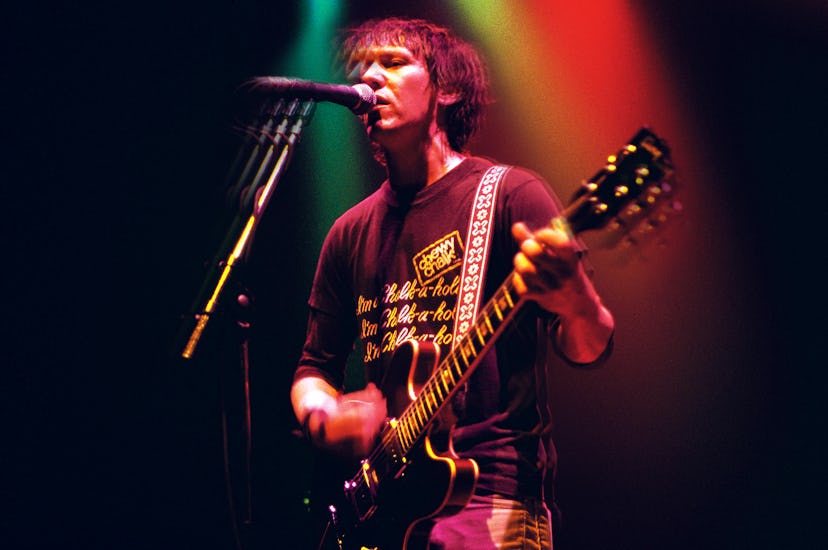

He stood alone on that massive stage at the 1998 awards show. Here was Elliott Smith, with an acoustic guitar strapped over his silvery-white suit, playing the Oscars after superstar Céline Dion had already taken her bow. He quietly plucked his way through “Miss Misery”; then, Madonna stepped onto the stage to present the Oscar for Best Original Song. As she read out the list of nominees—a tough race that included Michael Bolton’s “Go the Distance,” LeAnn Rimes’s “How Do I Live, and of course “My Heart Will Go On”—she paused when she arrived at the theme from Good Will Hunting. A smile playing at the corners of her mouth, she announced, “‘Miss Misery,’ music and lyrics by Elliott Smith.”

He lost, but he was Madonna’s, too.