Why Elizabeth Wurtzel, Who Died at 52, Was a Cultural Force

Elizabeth Wurtzel, the author of Prozac Nation: Young and Depressed in America, has died of metastatic breast cancer at age 52. She wrote several memoirs over the course of her lifetime, though it was her first—a retelling of the drug addiction, clinical depression, sex, and suicide attempt that defined her days as a Harvard student—that made the most waves. She was 27 when it published in 1994, at which point the New York Times Book Review christened her “Sylvia Plath with the ego of Madonna”—a descriptor she later made her Twitter bio.

But the memoir’s implications reached much further than simply Wurtzel’s career. With Prozac Nation, she pioneered the art of simultaneous self-awareness and self-indulgence, thereby reviving the memoir and creating a new (and now omnipresent) form of confessional writing. Arguably equally crucially, it set a different sort of precedent—that women who dare to unflinchingly scrutinize their personal lives in public will be derided as self-involved narcissists. Not that that deterred writers like Cat Marnell and Lena Dunham from following in her proto-influencer footsteps. (Tellingly, Caroline Calloway at one point owned multiple copies of Prozac Nation—a fact that Wurtzel found baffling.)

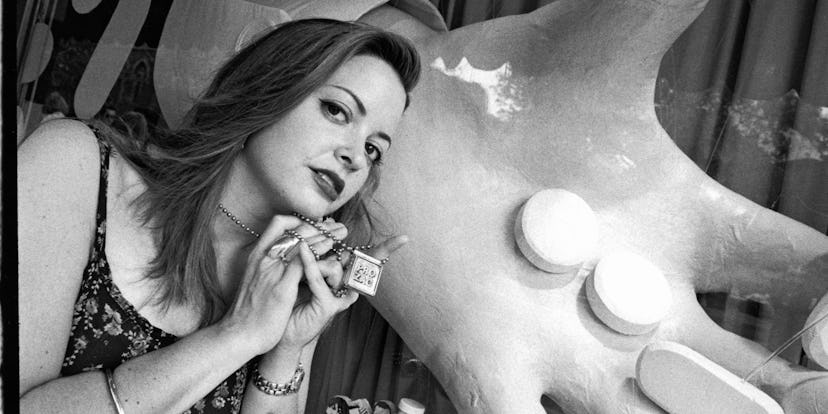

Born in 1967 in New York City, Wurtzel was six when she wrote her first book — and 11 when she began going to therapy and struggling with self-harm. (Her father was the civil rights photographer Bob Adelman, though Wurtzel herself only discovered as much in 2016.) Perhaps it’s best to let Wurtzel, a precocious master of self-introspection, sum up her early life herself: “I was on Prozac when it was still called fluoxetine,” she wrote in the Guardian in 2018. “I wrote a twentynothing memoir when there was no such thing. I got addicted to snorting Ritalin before there was Adderall. I was a riot girl, I was a do-me feminist, and I posed topless, giving the world the finger, on the cover of my second book.”

In that particular instance, Wurtzel was not simply navel-gazing. It was her point of entry for asserting, “I am worse than cancer. And now I have cancer,” in an essay about why she never struggled to come to terms with having the disease. Not for the first time, she also called attention to the BRCA mutation, as she’d done ever since learning she was BRCA-positive in 2015. That year, Wurtzel had three surgeries over the course of six months, including a double mastectomy. Naturally, she wrote about the experience, simultaneously issuing a call to action of sorts for women—specifically Ashkenazi Jewish women like herself—to get tested for the BRCA mutation. (One in 400 women is BRCA-positive, versus one in 40 Ashkenazi Jews.)

But before she wrote about cancer, Wurtzel wrote about depression. She’d been depressed for 17 years by the time she published Prozac Nation, and yet was still decades younger than Susanna Kaysen and William Styron—authors of Girl, Interrupted and Darkness Visible, respectively—when their titles came together to open a dialogue about mental health. “I was born with a mind that is compromised by preternatural unhappiness, and I might have died very young or done very little,” Wurtzel reflected in 2013. “Instead, I made a career out of my emotions.”

Related: Daphne Merkin on Her Depression and the Unrequited Lifelong Love at Its Root